![Police Misconduct Attorney]() ORANGE COUNTY POLICE MISCONDUCT SUMMARY

ORANGE COUNTY POLICE MISCONDUCT SUMMARY

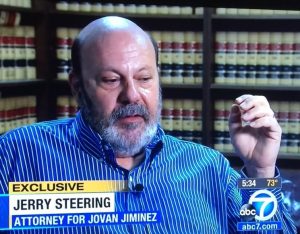

Jerry L. Steering, Esq., is a Police Misconduct Lawyer, serving, among other places, Orange County, and the Orange County cities shown below.

Mr. Steering has been suing police officers, and defending bogus criminal cases (mostly bogus crimes against police officers), for 29 years. The majority of our firm’s law practice, is suing police officers and other government officials, for claims such as false arrest, police brutality /excessive force, malicious prosecution, and other “Constitutional Torts” , including police whistleblowing cases (Cal. Labor Code Section 1102.5.)

Jerry L. Steering represents the victims of ”Police Misconduct”, such as the victim of the use of excessive force and false arrests of innocents. Mr. Steering’s law practice serves Orange County, and the Orange County cities shown below, as well as Ventura County, LA County, San Diego County, Riverside County and San Bernardino County. He has successfully handled many against Orange County law enforcement agencies, including cases against the Orange County Sheriff’s Department and local police agencies, such as:

victim of the use of excessive force and false arrests of innocents. Mr. Steering’s law practice serves Orange County, and the Orange County cities shown below, as well as Ventura County, LA County, San Diego County, Riverside County and San Bernardino County. He has successfully handled many against Orange County law enforcement agencies, including cases against the Orange County Sheriff’s Department and local police agencies, such as:

Gomez v. County of Orange, et al., U.S. Dist. Court, Central District of  California (LA) (2011) obtained $2,163,799.53 for unreasonable force on convicted jail inmate;

California (LA) (2011) obtained $2,163,799.53 for unreasonable force on convicted jail inmate;

Torrance v. County of Orange, et al., U.S. District Court,  Central District of California (Santa Ana)(2010); obtained $380,000.00 for unreasonable force and false arrest;

Central District of California (Santa Ana)(2010); obtained $380,000.00 for unreasonable force and false arrest;

Chamberlain v. County of Orange et al., U.S. District Court, Central District of California (Santa Ana)(2009); obtained $600,000.00 for failure to protect pre-trial detainee in Orange County Jail;

obtained $600,000.00 for failure to protect pre-trial detainee in Orange County Jail;

Baima v. County of Orange, et al; U.S. District Court, Central District of California (Santa Ana)(2003); obtained $208,000.00 for false arrest / unreasonable force.

Celli v. County of Orange, et al; U.S. District Court, Central District of California (Santa Ana)(2009); obtained $200,000.00 for false arrest / unreasonable force.

Celli v. County of Orange, et al; U.S. District Court, Central District of California (Santa Ana)(2009); obtained $200,000.00 for false arrest / unreasonable force.

Richard “Danny” Page v. City of Tustin , et al., U.S. District Court (Santa Ana) (1992); $450,000.00 for false arrest and unreasonable force.

Farahani v. City of Santa Ana; Mr. Steering obtained a $612,000.00 jury verdict against a Santa Ana Police Department officer for unreasonable force, for a single baton strike to a young man’s head. Farahani v. City of Santa Ana; United States District Court, Central District of California.

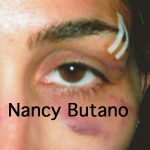

Butano v. County of Orange, et al.; U.S. Dist. Court, Central District of California (Santa Ana) (2013); $727,500.00 for false arrest and unreasonable force.

Butano v. County of Orange, et al.; U.S. Dist. Court, Central District of California (Santa Ana) (2013); $727,500.00 for false arrest and unreasonable force.

Sharp v. City of Garden Grove, Orange County Superior Court (2000): Mr. Steering obtained a $1,110,000.00 jury verdict against Garden Grove Police Department officers, along with a CHP officer and state parole agents, for the warrantless search of the body shop that was owned by the parolee’s father, and where the parolee worked when he wasn’t in prison. The parole department had denied GGPD Narcotics Bureau permission to do a “parole search” of the plaintiff father’s body shop, as they had no authority to do so. Parole agents can’t do (or authorize others to do) warrantless “parole searches” of places where parolees are employed. Imagine a parolee getting a job as a mechanic at Pep Boys. Could state parole agents and police officers do a parole search of Pep Boys? Of Course Not. State parole knew this, and they told GGPD Narcotics the same. However, GGPD Narcotics decided to use the pretext of a parole search, to do a full blown warrantless search of the Dad’s auto body shop, for a suspected meth lab, because the son / parolee’s parole officer wanted to violate the son’s parole for dirty drug tests, and was tired of waiting for GGPD to find him “cooking meth” at the Dad’s body shop GGPD had asked the Parole Agent not to violate the son / parolee’s parole, until they could catch him in the act of meth “cooking” at the Dad’s body shop; something that the mere appearance of in itself should be sufficient to dispel and such suspicion. The body shop was triangular, the hypotenuse of which, was wide open (no blinds or shades) to anyone standing on the sidewalk. The sidewalk side also had two wide entry bays, as did the rear side, the shop and doors were wide open all day, with all areas (save the lavatories) visible to any interested parties. The body shop also had an EPA approved vapor blower exhaust fan and roof portal, and any “dirty socks” odor from a meth lab, would have been blown all over the neighborhood. No reasonable officer would have really believed that the body shop was being used as a drug lab.

officers, along with a CHP officer and state parole agents, for the warrantless search of the body shop that was owned by the parolee’s father, and where the parolee worked when he wasn’t in prison. The parole department had denied GGPD Narcotics Bureau permission to do a “parole search” of the plaintiff father’s body shop, as they had no authority to do so. Parole agents can’t do (or authorize others to do) warrantless “parole searches” of places where parolees are employed. Imagine a parolee getting a job as a mechanic at Pep Boys. Could state parole agents and police officers do a parole search of Pep Boys? Of Course Not. State parole knew this, and they told GGPD Narcotics the same. However, GGPD Narcotics decided to use the pretext of a parole search, to do a full blown warrantless search of the Dad’s auto body shop, for a suspected meth lab, because the son / parolee’s parole officer wanted to violate the son’s parole for dirty drug tests, and was tired of waiting for GGPD to find him “cooking meth” at the Dad’s body shop GGPD had asked the Parole Agent not to violate the son / parolee’s parole, until they could catch him in the act of meth “cooking” at the Dad’s body shop; something that the mere appearance of in itself should be sufficient to dispel and such suspicion. The body shop was triangular, the hypotenuse of which, was wide open (no blinds or shades) to anyone standing on the sidewalk. The sidewalk side also had two wide entry bays, as did the rear side, the shop and doors were wide open all day, with all areas (save the lavatories) visible to any interested parties. The body shop also had an EPA approved vapor blower exhaust fan and roof portal, and any “dirty socks” odor from a meth lab, would have been blown all over the neighborhood. No reasonable officer would have really believed that the body shop was being used as a drug lab.

After several failed parole test drug tests by the son / parolee, his Parole Agent was getting more anxious to violate the son / parolee’s parole. So, the geniuses at the GGPD, the CHP and state parole (both members of OCATT; Orange County Auto-Theft task force.) They stormed into the body shop with SWAT / raid type gear, rifles and pistols blazing, ran-up from behind Mr. Sharp and pointed a shotgun at him. Then the cuffed-him (still at gunpoint) and made him get down onto the cement floor of his shop, with his hands cuffed behind him. One might imagine that this might result in knee injury to a 59 year old man, and one would be right. However, Mr. Sharp treated his own condition with health food supplements (Glucosamine Chondroitin). The constables then ransacked the body shop, with Mr. Sharp still cuffed, lying on the floor of his shop, with the neighboring businesses wondering why their business neighbor, who they always knew as a kind and generous man, was being treated like some despicable sub-human type, and in such a degrading and humiliating manner.

In addition to first claiming the the officers warrantless invasion of the shop and the seizure of Mr. Sharp (something ultimately rejected by the court) the cops also claimed that the search was justified as a warrantless search for stolen vehicle parts pursuant to Cal. Veh. Code § 2805; a real stretch (body shops don’t call in VIN numbers on cars brought in for repair. They are also neither U.S. Customs, nor the police. They’re not buying the car; they’re just fixing it.)

The Orange County Superior Court jury awarded Mr. Sharp $1,010,000.00 (ten thousand dollars of which was for punitive damages against the most culpable parole agent.) They didn’t believe the police; probably because they lied through their teeth, and finally violated someone who was just like one of them; the Orange County jurors (i.e. white, businessman with a trade, married High School sweetheart, enlisted in United States Marines, no criminal record, wife blond and very nice.) The GGPD officer who lead the raid on the body shop is now a Captain at GGPD.

Oliver v. City of Anaheim, U.S. District Court, Santa Ana; Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, 2012; (plaintiff won case in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals on their unlawful arrest claim; false arrest as matter of law.) Plaintiffs obtained $400,000.00 for four hour false arrest of father (and son), for father telling police that he didn’t know of his son hit a opossum with a shovel (which isn’t a crime anyway),so busted the father for violation of Cal. Penal Code 32 (i.e. “accessory to crime”, for not incriminating his son, for something that isn’t a crime. See, Oliver v. City of Anaheim; Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

unlawful arrest claim; false arrest as matter of law.) Plaintiffs obtained $400,000.00 for four hour false arrest of father (and son), for father telling police that he didn’t know of his son hit a opossum with a shovel (which isn’t a crime anyway),so busted the father for violation of Cal. Penal Code 32 (i.e. “accessory to crime”, for not incriminating his son, for something that isn’t a crime. See, Oliver v. City of Anaheim; Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Mr. Steering has also had many acquittals in Orange County Superior Court; especially in cases involving false arrests.

EXCESSIVE FORCE, FALSE ARREST AND MALICIOUS PROSECUTION CASES

Mr. Steering has been suing police officers, and defending bogus criminal cases of crimes against police officers, since 1984. The majority of our firm’s law practice, is suing police officers and other government officials, for claims such as false arrest, police brutality / excessive force, malicious prosecution, and other “Constitutional Torts“, and defending bogus criminal cases against the victims of such abuse by the police; almost always for the same incident that the civilian – victim sues for.

WHAT IS “EXCESSIVE FORCE”?

The Politics Of The Judge Or Jurors Are The Major Determinate Factor In Excessive Force Cases

In the real world, in real Courts with real juries and real judges, a determination as to whether a peace officer used “Excessive Force” in a any given situation, is as much of a political question, as a factual one. It is the trier of fact’s (the jury’s) political persuasion, their life experiences with law enforcement, and their world view, that is most likely the determinate factor in any a police brutality / excessive force cases.

Civilians who are (almost always falsely) accused of battering a peace officer, very often get criminally prosecuted for not cooperating with the beating fast enough, so as to constitute a “resisting” or “obstructing” or “delaying” of a peace officer engaged in the performance of his/her official duties; Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1); the most abused Section in the California Penal Code, and the most ambiguous, amorphous, and abused law in California (See our Tab for “Contempt of Cop Cases”, above.) The Section 148(a)(1) charge is either a throw-in for a more serious assault and battery of a peace officer charge (95% of which are bogus), or the base criminal charge itself.

Because of the ambiguous / amorphous language of Section 148(a)(1), a white jury has free reign to criminalize “failures of the attitude test“, when they believe that they would have acted otherwise (even though if some cops walked-up to them on the street and ordered them to prone-out and spread ‘em, they would throw a fit. ) A different jury, however, one not so white and Republican (the cops can do no wrong), say one in Compton, California, are likely to have a different view of the world, a different view of the police and a totally different verdict in an excessive force case.

Excessive Force In The Real World; The Rodney King Case.

Rodney King may have been and may represent a lot of things to a lot of people, but he still was a haphazard petty criminal. Let’s no make no mistake about that. He is not a role model or a martyr. He was just some man who got beat-up by the LAPD on March 3, 1991, whose beating happened to by video recorded by an amateur photographer. However, back in 1991, if you did have a video camera, it was most likely one that uses a full-sized VHS tape, and was used by propping it on top of one’s shoulder while filming. Nowadays, every 12 year old has an iPhone and could record a much better image. There are a lot of people getting beaten-up today by the police, but still, none that had the international impact than Rodney King’s beating did.

Rodney King, a man who first evaded a traffic stop by LAPD for errant driving, and who eventually stopped his vehicle, got his a__ kicked by pursuing LAPD officers. Mr. King’s beating was captured on a video recording, that showed several LAPD officers clobbering Mr. King with their batons, and beating and kicking him; all of it being obviously just plain wrong and cruel.

beating was captured on a video recording, that showed several LAPD officers clobbering Mr. King with their batons, and beating and kicking him; all of it being obviously just plain wrong and cruel.

The Rodney King Case; The Jurors In Simi Valley Find No Wrong By Police.

LAPD police officers Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno were criminally charged by LA County District Attorney Gil Garcetti with using unreasonable force on a Rodney King, and other nasties. Mr. Garcetti was confident that his video recording of Rodney King’s beating showing outrageous force by the LAPD, that even the fine people of Simi Valley would see things his way, and that convictions of the LAPD officers was imminent.

However, the defendant officers obtained a change of venue, to the California Superior Court in Simi Valley, Ventura County, California. The media had already convicted the four cops who got criminally prosecuted for the March 3, 1991 beating, but the geniuses in the LA County District Attorney’s Office and those in the media forgot one thing; that even now, Simi Valley is only 1.26% African-American, and that most of them are probably cops or cop lovers (otherwise, they wouldn’t move there.) Convincing them that the Constables were the bad guys, and that the fleeing intoxicated motorist is the victim, is like trying to convince Billy Graham that there is no God. Sorry, you’re not going to do it.

On April 29, 1992 the jury in the Ventura County Superior Court (Simi Valley) criminal case, found that the defendant LAPD officers didn’t use “Excessive Force” upon Rodney King on March 3, 1991, and acquitted Stacey Koon, Laurence Powell, Timothy Wind, and Theodore Briseno of all charges. LA went crazy.

Some people reacted with disbelief to the jury verdicts; others reacted in anger. A crowd outside the Ventura County Courthouse shouted “Guilty! Guilty!” as the defendants were escorted away by sheriff’s deputies. According to Rodney King’s bodyguard, Tom Owens, King sat “absolutely motionless” as he watched in “pure disbelief” the televised verdicts being read. A visibly angry Mayor Tom Bradley publicly declared, “Today, the jury told the world that what we all saw with our own eyes was not a crime.”

Sixty-two minutes after the King verdict, five black male youths entered a Korean-owned Pay-less Liquor and Deli at Florence and Dalton Avenues. The youths each grabbed bottles of malt liquor and headed out the door, where they were blocked by the son of the store’s owner, David Lee. One young man smashed Lee on the head with a bottle, while two others shattered the storefront with their thrown bottles. One of the youths shouted, “This is for Rodney King!” The deadly LA riots of 1992 were underway.

Pay-less Liquor and Deli at Florence and Dalton Avenues. The youths each grabbed bottles of malt liquor and headed out the door, where they were blocked by the son of the store’s owner, David Lee. One young man smashed Lee on the head with a bottle, while two others shattered the storefront with their thrown bottles. One of the youths shouted, “This is for Rodney King!” The deadly LA riots of 1992 were underway.

Events grew increasingly ugly. Black youths with baseball bats battered a car driven by a white. Another white driver was hit in the face by a chunk of concrete thrown threw his car windshield. Police faced gangs of rock and bottle-throwing youths. The taunting, missile-hurling crowds grew in size, forcing the police to beat a hasty retreat out of the riot area. The Florence-Neighborhood is left to the anarchy of the mob attacking helpless civilians.

Perhaps the most horrific image of the riots involved mild-mannered truck driver Reginald Denny. Denny was at the wheel of his eighteen-wheeler, carrying a load of sand and  listening to country music, when at 6:46 P.M. he entered the intersection at Normandie and Florence. A helicopter overhead captured on videotape what occurred next. Denny was pulled from his truck into the street, where he was kicked and then beaten on the head with a claw hammer. The most vicious attack came from Damian Williams who smashed a block of concrete on Denny’s head at point-blank range, knocking him unconscious and fracturing his head in ninety-one places. The helicopter camera recorded Williams doing a victory dance as he gleefully pointed out Denny’s bloodied figure.

listening to country music, when at 6:46 P.M. he entered the intersection at Normandie and Florence. A helicopter overhead captured on videotape what occurred next. Denny was pulled from his truck into the street, where he was kicked and then beaten on the head with a claw hammer. The most vicious attack came from Damian Williams who smashed a block of concrete on Denny’s head at point-blank range, knocking him unconscious and fracturing his head in ninety-one places. The helicopter camera recorded Williams doing a victory dance as he gleefully pointed out Denny’s bloodied figure.

The Governor called-out the National Guard, who even deployed in full Combat gear, even in the County Courthouses. When the rioting finally ended five days later, fifty-four people (mostly Koreans and Latinos) were dead–the greatest death toll in any American civil disturbance since the 1863 Draft Riots in New York City. Hundreds of people (including sixty firefighters) were injured. Looting and fires had resulted in more than one billion dollars in property damage. Whole neighborhoods in south central LA, such as Korea town, looked like war zones. Over 7,000 persons were arrested.

Even as the rioting continued, President George Bush and Attorney General William Barr began the process of bringing federal charges against the four LAPD officers accused in the King case. On the day after the Simi Valley verdict, Bush issued a statement declaring that the verdict “has left us all with a deep sense of personal frustration and anguish.” In a May 1, 1993 televised address to the nation, Bush all but promised a federal prosecution of the officers.

The Rodney King Case; Here Come The Feds.

Prosecuting the officers on the federal charge of violating King’s civil rights accomplished two Bush Administration goals. The first goal was to control the rage that had developed in black communities. The second was to reduce demands from some in the civil rights community for sweeping investigations into police misconduct.

On May 7, federal prosecutors began presenting evidence to a LA grand jury. On August 4, the grand jury returned indictments against the three officers for “willfully and intentionally using unreasonable force” and against Koon for “willfully permitting and failing to take action to stop the unlawful assault.” on King.

intentionally using unreasonable force” and against Koon for “willfully permitting and failing to take action to stop the unlawful assault.” on King.

Unlike the Simi Valley jury, the federal jury was racially mixed. Although the defense made a considerable effort to exclude African-Americans, two blacks were seated as jurors. One of the two, Marian Escobel (“Juror No. 7), sent an early signal of the difficulty she would cause the defense when she was overheard strongly criticizing the defense’s treatment of other potential black jurors. In one of his most important trial rulings, Judge Davies denied a defense motion to remove Escobel from the jury–perhaps because he understood that the juror accurately perceived the defense conduct. A second problem for the defense resulted from their focus on excluding African-American jurors: they gave insufficient attention to identifying and excluding white jurors who were especially fearful of producing a verdict that would cause more rioting.

In addition to a more favorable jury, the prosecution had other advantages in the second trial. Clymer noted later that the government “had the advantage of seeing everything that had gone wrong in the first trial.” Clymer excluded from the witness list those witnesses who had backfired in Simi Valley. He avoided juror suspicion that the prosecution was hiding something by calling Rodney King to the stand. He came up with a medical expert who would prove King’s facial injury came from a baton blow, not the asphalt. He identified a credible use-of-force expert, Mark Conta, who countered the testimony of the defense’s expert. He used cross-examination to suggest that defense police witnesses were friends seeking to bail the defendants out of a tight spot. Finally, he presented new and potentially damaging facts to present to the jury, such as Powell taking King on a ninety-minute detour to Foothill Station after leaving Pacifica Hospital, rather than directly to the USC Medical Center, as Koon had requested. Clymer hoped that the jury might conclude the detour was made to show off their injured “trophy.”

King may have been an ex-con who had given wildly different accounts of his beating, but he came across on the stand as an uneducated man was either too drunk or confused to remember events, not as a sophisticated liar. Through King’s testimony, the jurors saw a man who seemed to have been in genuine fear of his life. He also raised the issue of race. Although he at first had denied that race had anything to do with his beating, he told the jury that as he was being hit, the officers “were chanting either ‘What’s up killer? How do you feel killer? [or] What’s up nigger?” Asked whether the word used was “killer” or “nigger,” King answered, “I’m not sure.” Watching King testify, defense attorney Stone worried. He saw King as “very polite and mild-mannered and thoughtful” and that, he said, “spells credibility.”

On April 10, 1993 two LAPD officers, Sgt. Stacey Koon and Laurence Powell, were convicted in the United States District Court for the Central District of California, for violation of 18 U.S.C. § 241; violation of federal Constitutional rights under the color of law; felonies, for beating-up Rodney King. The Rodney King convictions would reshape the entire issue of the excessive use of force by the police in America. Unfortunately, White Republicans don’t see the world any differently.

LEGAL DEFINITIONS OF EXCESSIVE FORCE.

The United States Supreme Court has defined “Excessive Force” as follows:

“Where, as here, the excessive force claim arises in the context of an arrest or investigatory stop of a free citizen, it is most properly characterized as one invoking the protections of the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees citizens the right “to be secure in their persons . . . against unreasonable . . . seizures” of the person . . . . . . . Determining whether the force used to effect a particular seizure is “reasonable” under the Fourth Amendment requires a careful balancing of ” ‘the nature and quality of the intrusion on the individual’s Fourth Amendment interests’ ” against the countervailing governmental interests at stake. Id., at 8, 105 S.Ct., at 1699, quoting United States v. Place, 462 U.S. 696, 703, 103 S.Ct. 2637, 2642, 77 L.Ed.2d 110 (1983). Our Fourth Amendment jurisprudence has long recognized that the right to make an arrest or investigatory stop necessarily carries with it the right to use some degree of physical coercion or threat thereof to effect it. See Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S., at 22-27, 88 S.Ct., at 1880-1883. Because “the test of reasonableness under the Fourth Amendment is not capable of precise definition or mechanical application,” Bell v. Wolfish, 441 U.S. 520, 559, 99 S.Ct. 1861, 1884, 60 L.Ed.2d 447 (1979), however, its proper application requires careful attention to the facts and circumstances of each particular case, including the severity of the crime at issue, whether the suspect poses an immediate threat to the safety of the officers or others, and whether he is actively resisting arrest or attempting to evade arrest by flight. See Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S., at 8-9, 105 S.Ct., at 1699-1700 (the question is “whether the totality of the circumstances justifies a particular sort of . . . seizure”).” (See, Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386 (1989.)

“The “reasonableness” of a particular use of force must be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, rather than with the 20/20 vision of hindsight. See Terry v. Ohio, supra, 392 U.S., at 20-22, 88 S.Ct., at 1879-1881. The Fourth Amendment is not violated by an arrest based on probable cause, even though the wrong person is arrested, Hill v. California, 401 U.S. 797, 91 S.Ct. 1106, 28 L.Ed.2d 484 (1971), nor by the mistaken execution of a valid search warrant on the wrong premises, Maryland v. Garrison, 480 U.S. 79, 107 S.Ct. 1013, 94 L.Ed.2d 72 (1987). With respect to a claim of excessive force, the same standard of reasonableness at the moment applies: “Not every push or shove, even if it may later seem unnecessary in the peace of a judge’s chambers,” Johnson v. Glick, 481 F.2d, at 1033, violates the Fourth Amendment. The calculus of reasonableness must embody allowance for the fact that police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving about the amount of force that is necessary in a particular situation.

As in other Fourth Amendment contexts, however, the “reasonableness” inquiry in an excessive force case is an objective one: the question is whether the officers’ actions are “objectively reasonable” in light of the facts and circumstances confronting them, without regard to their underlying intent or motivation. See Scott v. United States, 436 U.S. 128, 137-139, 98 S.Ct. 1717, 1723-1724, 56 L.Ed.2d 168 (1978); see also Terry v. Ohio, supra, 392 U.S., at 21, 88 S.Ct., at 1879 (in analyzing the reasonableness of a particular search or seizure, “it is imperative that the facts be judged against an objective standard”). An officer’s evil intentions will not make a Fourth Amendment violation out of an objectively reasonable use of force; nor will an officer’s good intentions make an objectively unreasonable use of force constitutional. See, Scott v. United States, supra, 436 U.S., at 138, 98 S.Ct., at 1723, citing United States v. Robinson, 414 U.S. 218, 94 S.Ct. 467, 38 L.Ed.2d 427 (1973).”

In Graham, we held that claims of excessive force in the context of arrests or investigatory stops should be analyzed under the Fourth Amendments objective reasonableness standard, not under substantive due process principles. 490 U.S., at 388, 394. Because police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving about the amount of force that is necessary in a particular situation, id., at 397, the reasonableness of the officers belief as to the appropriate level of force should be judged from that on-scene perspective. Id., at 396. We set out a test that cautioned against the 20/20 vision of hindsight in favor of deference to the judgment of reasonable officers on the scene. Id., at 393, 396. Graham sets forth a list of factors relevant to the merits of the constitutional excessive force claim, requir[ing] careful attention to the facts and circumstances of each particular case, including the severity of the crime at issue, whether the suspect poses an immediate threat to the safety of the officers or others, and whether he is actively resisting arrest or attempting to evade arrest by flight. Id., at 396. If an officer reasonably, but mistakenly, believed that a suspect was likely to fight back, for instance, the officer would be justified in using more force than in fact was needed.” (See, Saucier v. Katz, 533 U.S. 194 (2001), Kennedy, J.)

objective reasonableness standard, not under substantive due process principles. 490 U.S., at 388, 394. Because police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving about the amount of force that is necessary in a particular situation, id., at 397, the reasonableness of the officers belief as to the appropriate level of force should be judged from that on-scene perspective. Id., at 396. We set out a test that cautioned against the 20/20 vision of hindsight in favor of deference to the judgment of reasonable officers on the scene. Id., at 393, 396. Graham sets forth a list of factors relevant to the merits of the constitutional excessive force claim, requir[ing] careful attention to the facts and circumstances of each particular case, including the severity of the crime at issue, whether the suspect poses an immediate threat to the safety of the officers or others, and whether he is actively resisting arrest or attempting to evade arrest by flight. Id., at 396. If an officer reasonably, but mistakenly, believed that a suspect was likely to fight back, for instance, the officer would be justified in using more force than in fact was needed.” (See, Saucier v. Katz, 533 U.S. 194 (2001), Kennedy, J.)

So, the Supreme Court (Justice Kennedy writing for the Majority) has essentially defined “excessive force” as basically force that is “unreasonable” in the abstract; that is, force that is greater than the amount of force that a reasonably well trained officer would have used under the same circumstances. Not so bad. Right? Not really. Here’s why.

THE PROBLEM WITH GRAHAM’S OBJECTIVE “REASONABLE OFFICER IN THE ABSTRACT STANDARD” IN THE REAL WORLD – THE ANALYSIS FOR WHETHER YOU CAN ACTUALLY SUE THE OFFICER FOR EXCESSIVE FORCE ISN’T ALL THAT OBJECTIVE.

The problem with the description of how what excessive force is defined, is not the Supreme Court’s strong emphasis on the officer’s conduct being based on an “objective” standard; they hypothetical reasonable officer in the abstract. The problem is that this claim of objective reasonableness is bogus, for the subject belief of the subject officer is nonetheless considered in the excessive force analysis.

As shown above in the last sentence of the block quote from Saucier v. Katz:

“If an officer reasonably, but mistakenly, believed that a suspect was likely to fight back, for instance, the officer would be justified in using more force than in fact was needed.” (See, Saucier v. Katz, 533 U.S. 194 (2001).)

How can the standard really be an objective one, if the subject officer’s mistaken yet is considered at all? How can one mistakenly but reasonably believe something? What Saucier really says, and what that case was all about, is whether a reasonably well trained officer in the abstract, could have reasonably believed, that a particular use of force is reasonable, when the same reasonably well trained officer in the abstract, would believe that the use of force was unreasonable? Huh? This is more Orwellian newspeak:

abstract, would believe that the use of force was unreasonable? Huh? This is more Orwellian newspeak:

“The concern of the immunity inquiry is to acknowledge that reasonable mistakes can be made as to the legal constraints on particular police conduct. It is sometimes difficult for an officer to determine how the relevant legal doctrine, here excessive force, will apply to the factual situation the officer confronts. An officer might correctly perceive all of the relevant facts but have a mistaken understanding as to whether a particular amount of force is legal in those circumstances. If the officer’s mistake as to what the law requires is reasonable, however, the officer is entitled to the immunity defense.” See, Saucier v. Katz; Majority Opinion by Justice Kennedy.

So, according to Justice Kennedy, although the reasonable force determination is one that is to be made in the abstract, when it comes to whether a particular police officer should be held liable for his Constitutional violations, objectivity goes out the window, and a reasonably mistaken belief by a particular defendant officer, is a sufficient defense to civil liability? So, one can reasonably act unreasonably. George Orwell would be proud of the Justice Kennedy’s fluency with newspeak.

the Justice Kennedy’s fluency with newspeak.

THE PROBLEM WITH GRAHAM’S OBJECTIVE “REASONABLE OFFICER STANDARD” IN THE REAL WORLD – THE WATCHMAN GETS TO MAKE HIS OWN RULES THAT REGULATE HIS OWN CONDUCT

The problem is, that the standards in the police profession for what is “reasonable” or otherwise proper police conduct in a given situation, are generally neither the creature of legislation (i.e. state law requiring the audio recording of custodial police interrogations) nor the product of any judicially created mandate, duty, or prohibition (i.e. Constitutional limits on conduct and judicially created “exclusionary rule”.) The conduct of “the objectively reasonable officer”; that standard that the Supreme Court attempted to describe in Graham v. O’Connor and Saucier v. Katz, is created by the very persons whose conduct the Fourth Amendment is supposed to impose limits on. Thus, in a very real sense, the Supreme Court has set the standard (“objectively reasonable officer”) that the Fourth Amendment requires, but has delegated the details of what’s reasonable or not, to the police.

It’s letting the regulated enact their own regulations. It’s like letting the local power company, set the rate of profit that they should make; set the formula for how the amount of profit is determined; set how much they can spend on public relations (since they’re a monopoly), and how, when, by whom and in what manner, they should be inspected, what they can and can’t do in their industry, and every other aspect of the business. If they want to all use tasers on civilians, then that’s reasonable. If they all want to pepper-spray persons because their hands in their pockets, then that’s reasonable. If they want to prone-out everyone at gun point that they detain, then that’s reasonable. At the end of the day, in the real world police world, if the technique, method, procedure, policy or practice reduces the danger level to the officer, you can bet that, eventually, they will find a way to justify such technique, method, procedure, policy or practice , and make such otherwise unreasonable behavior, “reasonable”, for no other reason than the police would prefer to act that way; Constitutional or not. You see the problem. The police have an old slogan: “It’s better to be judged by 12, then carried by 6.” It’s another way of saying, I’ll act in a way that is in my self interest; not yours, and if I happen to trample your Constitutional rights, so be it.

persons because their hands in their pockets, then that’s reasonable. If they want to prone-out everyone at gun point that they detain, then that’s reasonable. At the end of the day, in the real world police world, if the technique, method, procedure, policy or practice reduces the danger level to the officer, you can bet that, eventually, they will find a way to justify such technique, method, procedure, policy or practice , and make such otherwise unreasonable behavior, “reasonable”, for no other reason than the police would prefer to act that way; Constitutional or not. You see the problem. The police have an old slogan: “It’s better to be judged by 12, then carried by 6.” It’s another way of saying, I’ll act in a way that is in my self interest; not yours, and if I happen to trample your Constitutional rights, so be it.

THE PROBLEM WITH GRAHAM’S OBJECTIVE “REASONABLE OFFICER STANDARD” IN THE REAL WORLD – QUALIFIED IMMUNITY.

As shown in the last sentence of the quote from Saucier v. Katz, immediately above:

“If an officer reasonably, but mistakenly, believed that a suspect was likely to fight back, for instance, the officer would be justified in using more force than in fact was needed.” (See, Saucier v. Katz, 533 U.S. 194 (2001).) What does that mean? It means whie

In a nutshell, the Qualified Immunity is an immunity from a lawsuit for violation of a civilian’s Constitutional rights, when those rights were actually violated, but a reasonably well trained police officer could have believed that his conduct did not constitute such Constitutional violation. So, even if the police officer actually violated your Constitutional Rights, he may be immune from suit, because the law was not clearly established enough at the time of the violation, to hold a police officer liable for his conduct. This is a doctrine “contrived” by the conservative members of the Supreme Court (since 1981), to ensure that you can’t do anything about (or at least do a whole lot less about) your Constitutional Rights being trampled by the government.

So, for example, if the police come-up with a whole new technique to restrain people, such as a with a taser, or pepper-spray, or pepper-balls, or water-balls, or hobbling (police hog tying), or a shock-belting, or stun-gunning, the officer may very well be entitled to qualified immunity from being sued for the misuse of any of the above-mentioned devices; not because its “reasonable”, but because the police just use those devices in such manners; thereby giving the Courts an excused to relieve the police officer from liability for the damage caused by his violation of the Constitutional Rights of civilians:

However, a trial court should not grant summary judgment when there is a genuine dispute as to the facts and circumstances within an officers knowledge or what the officer and claimant did or failed to do. Id.” (Saucier v. Katz, supra.)

So, according to Justice Kennedy, although the reasonable force determination is one that is to be made in the abstract, when it comes to whether a particular police officer should be held liable for his Constitutional violations, objectivity goes out the window, and a reasonably mistaken belief by a particular defendant officer, is a sufficient defense to civil liability? So, one can reasonably act unreasonably.

WHY THE POLICE CRIMINALLY PROSECUTE THEIR VICTIMS

Unfortunately, because of institutional pressures (i.e. “ratting out fellow officer not a good career move), and the obvious political and practical consequences of not backing-up the their fellow officers, the norm in today’s police profession, is for peace officers to falsely arrest their “victims”, and to author false police reports to procure the bogus criminal prosecutions (i.e. to literally “frame” others) of those civilians whose Constitutional rights and basic human dignity have been violated; to justify what they did, and to act in conformity with that justification. The excessive force victims get criminally prosecuted, for crimes that they didn’t commit; usually for crimes such as “Resisting / obstructing / delaying a peace officer in the lawful performance of their duties (Cal. Penal Code148(a)(1)), assault on a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code § 240 / 241), “battery on a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code § 242 / 243(b)) (which is almost always, in reality, battery by a peace officer; otherwise known as “Excessive Force” or “Unreasonable Force”), and resisting officer with actual or threat of violence (Cal. Penal § Code 69.) Section 69 is a “wobbler” under California law; a crime that the government can charge as either a misdemeanor or a felony. This charge is usually reserved for cases in which the police use substantial force on the innocent arrestee (the real “victim”), and need to falsely claim more violent / serious conduct by the “victim” to justify their outrages.

So, for example, the crime of “battery on a peace officer” (Cal. Penal Code § 242 / 243(b)), is almost always, in reality, “battery by a peace officer”; otherwise known as “Excessive Force”; an “unreasonable seizure” of a person under the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution (See, Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386 (1989).)

If you have been the victim of Excessive Force by a police officer, please check our Section, above, entitled: “What To Do If You Have Been Beaten-Up Or False Arrested By The Police“. Also, please click on “Home“, above, or the other pages shown, for the information or assistance that we can provide for you. If you need to speak with a lawyer about your particular legal situation, please call the Law Offices of Jerry L. Steering for a free telephone consultation.

MOST FALSE ARRESTS ARE EFFORTS BY POLICE OFFICERS TO PROTECT THEMSELVES FROM CIVIL, CRIMINAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE LIABILITY, FOR OTHER WRONGFUL ACTS COMMITTED BY THEM

Police Misconduct is rampant and condoned and defended by the command structure of most, if not all, modern police agencies. Modern police agencies are afraid of losing their “power” in and over a community. That “power base”, is based in large part, on the public “supporting the police”. That popular support is based upon a belief by the body politic, that: 1) police officers have a difficult and dangerous job, 2) that they’re basically honest, 3) that only a small percentage of them would commit perjury, 4) that the force that the police use on people is almost always justified (if not legally, then morally), and that 5) police are capable of policing themselves. Although none of these beliefs are accurate, one cannot ignore the belief system of the majority of the white / affluent American populace, in understanding why police officers routinely, and without a second thought, falsely arrest civilians, and commit other outrages against innocents.

Wrongful police beatings, accompanied by their sister “false arrests”, are a common and every day occurrence. These beating / arrests are no longer limited to persons of color. Soccer Moms, airline pilots and school teachers, beware: because of the great (and ever expanding) powers being given to police officers by the Supreme Court, described below, in a very real way, you no longer have the right to question, protest or challenge police actions, since to do so usually results in your being physically abused and falsely arrested on trumped of charges of essentially, “Contempt Of Cop”; (i.e. maybe not getting on the ground fast enough, or failing to walk-over to the officer fast enough; some type of failing the attitude test.)

Unfortunately, because of institutional pressures (i.e. “ratting out fellow officer not a good career move) and the obvious political and practical consequences of not backing-up the their fellow officers, the norm in today’s police profession, is for peace officers to falsely arrest civilians, and to author false police reports, to procure the bogus criminal prosecutions (i.e. to literally “frame”) of those civilians whose Constitutional rights and basic human dignity have been violated by them. After all; how would it look if a police officer beat you up, and didn’t arrest you. Because most police officers, including those that step-over Constitutional “line in the sand” (i.e. beating another, falsely accusing civilians of crimes), are not true sociopaths, when they falsely charge you with a crime, it isn’t usually too serious of one. Most are bogus claims for violation of Cal. Penal Code 148(a)(1), because the crime of “resisting or obstructing or delaying a peace officer who’s engaged in the performance of his/her duties” is incredibly ambiguous, and can (ingenuously or ignorantly) be applied to almost any conduct by a person (i.e. the defendant yelled at me for restraining [torturing] the “suspect”, so he delayed me from arresting the “suspect” because I had to look his way and take a protective stance in the events that the defendant charged at me.)

WHY THE COPS CAN GET USUALLY GET AWAY WITH IT; AMERICANS’ BELIEF SYSTEM ABOUT POLICE OFFICERS

Most Americans have a deeply held belief that police officers don’t beat-up civilians who don’t deserve it. People believe what they want to believe, and they don’t want to believe that the persons entrusted with their safety, routinely beat-up and “frame” innocents; often for fun, or to bolster their frail egos. However, in the real world, many police officers do just that. A substantial minority of peace officers actually do beat, torture and falsely arrest those that defy their authority, or somehow bruise their fragile egos. Thus, in the real world, the crime of “battery on a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code § 242 / 243(b)), is almost always, in reality, battery by a peace officer; otherwise known as “excessive force” or “Unreasonable Force”, and the crime of resisting arrest (resisting or obstructing or delaying a peace officer; Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1)), is almost always the choice crime to arrest a civilian who committed no crime. The police can fairly easily obtain convictions of their victims for “resisting / obstructing / delaying a peace officer”, because almost any conduct by a civilian can be characterized as falling within the ambit of that statute; especially conduct that jurors find themselves believing is not the way that they would have handled that situation.

WHY THE COPS CAN GET USUALLY GET AWAY WITH IT; THE JURORS

To attack the jury system is to attack an institution that has been the primary barrier between oppression and freedom in the English speaking world since 1215. This is not an attack on the jury system. It is merely a reflection as to why in false arrest, unreasonable force and malicious prosecution cases, The way that a jury decides these type of cases is as much political, as it is an exercise in fact finding. The persons who ultimately get to sit on juries in these cases, have no real idea as to how police officers actually act, and have no idea how truly institutionally corrupt, police agencies really are when it comes to defending the County / City coffers and their and the politicians’ images.

unreasonable force and malicious prosecution cases, The way that a jury decides these type of cases is as much political, as it is an exercise in fact finding. The persons who ultimately get to sit on juries in these cases, have no real idea as to how police officers actually act, and have no idea how truly institutionally corrupt, police agencies really are when it comes to defending the County / City coffers and their and the politicians’ images.

In both civil and criminal cases, the parties have some say in the composition of the jury. The jury pool are supposedly called randomly, and the Court and the lawyers get to ask them questions. That part of a trial, questioning potential jurors, is called voir dire, that in French means, to speak the truth. Each side gets a certain numbers of peremptory challenges, that they can use to strike persons from sitting as jurors. In a federal court civil rights case, each side usually gets four peremptory challenges. So far, sounds fair. Here’s the rub.

Most people who have actually seen police officers beat-up a civilian have a lasting terrible feeling about police misconduct. Almost invariably, when they are asked by the lawyers or the Court about whether their prior experience with police misconduct will cause them to be prejudice against either side, they almost always say Yes. Most such people who have seen police beatings and the false prosecutions of their friends, are so deeply affected, that they invariably tell the Court that they are biased against police officers (in this type of case), and that they cant really put-aside that bias and be completely fair and impartial. Once they make that statement, any such jurors are then routinely excused for cause from sitting on that jury. Thus, the jurors who would more likely be favorable to the civil rights plaintiff (or criminal defendant accused of some crime against a peace officer), is excused for cause from sitting on the jury. The lawyer defending the case for the police doesn’t even had to use one of their jury peremptory challenges to get rid of that juror. All of the others jurors who do get to sit, are people who have never seen police misconduct; leaving a jury that, unfortunately, have no concept of the way that police, and police organizations, actually act.

Therefore, when Miss, Mrs. or Mr. Citizen gets falsely arrested, beaten-up or maliciously prosecuted by police agencies, and gets criminally prosecuted for conduct that often isn’t criminal (i.e. “creative use” of the California criminal statute Penal Code Section 148(a)(1)), these “sanitized jurors” will generally not believe that the police really did what Miss, Mrs. or Mr. Citizen claim that they did, unless Miss, Mrs. or Mr. Citizen’s attorney can really prove otherwise; real proof; like a video, audio, or a bus load of highly observant nuns with photographic memories who testified about clearly indefensible police conduct. That’s why the jury system rigged against persons victimized by the police; because the only people who ever get to sit in judgment in these type of cases as jurors, are persons who have never had a bad experience with a police officer, or and who has not seen outrageous police conduct. Their life experience tells them something that’s just not true; that police officer don’t beat people up unless they did something to deserve it. You, therefore, need great proof to dispel that belief by jurors.

WHY THE COPS CAN GET USUALLY GET AWAY WITH IT; AS A PRACTICAL MATTER, WE LIVE IN A POLICE STATE

If you think, as a practical matter, that you live in a free country, you’re wrong. We live in a police state; at least to a very appreciable degree. As a practical matter, the police can do whatever they want to you, and then procure the institution of a bogus criminal case against you. They typically author bogus police reports that claim that you committed some crime, like resisting / obstructing / delaying a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code §148(a)(1)) and/or battery on a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code § 242 / 243(b)), that results in a bogus criminal prosecution against you. They know that the District Attorney’s Office takes great pride in protecting the police from civil liability, by filing and prosecuting criminal action. They do this to beat you down; to make it so expensive for you to defend yourself on bogus criminal charges that carry little chance of actually being sentenced to jail, such as resisting arrest, that you end-up taking a plea bargain, that, in practical effect, bars your lawsuit by you for either false arrest, malicious prosecution, and, in most such cases, unreasonable force.

They also do this to protect themselves from internal discipline, and criminal liability for civil rights violations (18 U.S.C. § 242; violating a persons federal Constitutional rights under the color of state law.) The employing police agency will (almost) always deny that their officer engaged in wrongful conduct, especially in swearing contest type cases, where there is no video recording of the police beatings. Because the employing police agency will (almost) always back their officers by touting their (false) version of the story in order to avoid civil liability to the employing entity for the actions of their officers, it’s almost impossible to discipline them. For example, the City of Inglewood, California, fired Inglewood Police Department officer Jeremy Morse, for the video recording beating of a teenager at a gas station. When it came time for the civil suit against the City and the officers for the beating, the City contended that the officers acted properly. Accordingly, since the City took that position, fired officer Jeremy Morse sued the city, and won $2,1600,000.00 for his wrongful firing.

Inglewood Police Department officer Jeremy Morse, for the video recording beating of a teenager at a gas station. When it came time for the civil suit against the City and the officers for the beating, the City contended that the officers acted properly. Accordingly, since the City took that position, fired officer Jeremy Morse sued the city, and won $2,1600,000.00 for his wrongful firing.

FALSE ARREST CASES – DON’T CALL THE COPS UNLESS YOU WANT SOMEONE AT LEAST IN JAIL, OR VERY POSSIBLY DEAD

All of use have broken some sort of law, but most of us don’t go around holding-up liquor stores. The odds are, that if you are inquiring about a police misconduct case, such as a false arrest case, that you fall into three basic categories of ways that the police came into contact with you, and then falsely arrested you, or worse.

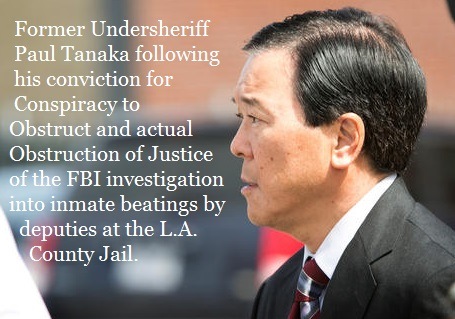

Former Undersheriff Paul Tanaka, along with a retired LASD Captain, were indicted on May 13, 2015 by a federal Grand Jury for Obstructing and Conspiring to Obstruct a federal Grand Jury investigation of the rampant torturing of inmates at the LA County Jail (See, Paul Tanaka Indictment of May 13, 2015.) That’s not the end of it. Former LASD Deputy Sheriff Noel Womack pleaded guilty in June of 2015 to federal charges of lying to the FBI about systemic LASD torturing and framing of inmates at the LA County Jails. In 2014, six LASD Deputy Sheriffs were convicted of obstructing the FBI’s investigation of the torturing of prisoners at the LA County Jails.

Former Undersheriff Paul Tanaka, along with a retired LASD Captain, were indicted on May 13, 2015 by a federal Grand Jury for Obstructing and Conspiring to Obstruct a federal Grand Jury investigation of the rampant torturing of inmates at the LA County Jail (See, Paul Tanaka Indictment of May 13, 2015.) That’s not the end of it. Former LASD Deputy Sheriff Noel Womack pleaded guilty in June of 2015 to federal charges of lying to the FBI about systemic LASD torturing and framing of inmates at the LA County Jails. In 2014, six LASD Deputy Sheriffs were convicted of obstructing the FBI’s investigation of the torturing of prisoners at the LA County Jails.

Lee Baca resigned from office over the scandal at the LA County Men’s Central Jail involving the Indictment of 18 LASD Deputy Sheriffs and their Supervisors for torturing prisoners and obstructing the FBI’s investigation of the same. On February 10, 2016, Sheriff Baca was Indicted for violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(2); lying to the FBI regarding his knowledge of a scheme in the Sheriff’s Department to intimidate an FBI agent who was investigating complaints of beatings of inmates by deputies at the LA County Jail, and to hide an FBI informant – jail inmate from his FBI handlers. Sheriff Baca was tried on that Indictment, but the jury hung.

Thereafter, on April 6, 2016, former LASD Undersheriff Paul Tanaka was convicted of conspiracy and actual obstruction of an FBI investigation; violation of 18 U.S.C. § 371 (conspiring to obstruct justice) and 18 U.S.C. § 1503(a) (obstructing justice); for not only obstructing an FBI investigation into years of beatings and torturing of inmates at the L.A. County Jail, but also Tanaka and other high ranking Sheriff’s Department officials threatened one of the FBI agents involved in that investigation with arrest for continuing that investigation. In his trial, Tanaka admitted that he still had the Minnesota Vikings Logo tattoo on his leg; a tattoo that he described as a member in a club; the “Vikings”; a tatoo that the federal courts have held is the gang taoo for a “neo-Nazi white supremacists gang within the LA County Sheriff’s Department. See, Thomas v. County of LA, 978 F.2d 504 (1992).

Thereafter, on February 10, 2017, former LA County Sheriff Lee Baca was convicted of similar charges; lying to the FBI and obstruction of the FBI investigation into the systemic beatings and torture of inmates at the LA County Jail; violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(2); lying to the FBI regarding his knowledge of a scheme in the Sheriff’s Department to intimidate an FBI agent who was investigating complaints of beatings of inmates by deputies at the LA County Jail, and to hide an FBI informant – jail inmate from his FBI handlers.

and torture of inmates at the LA County Jail; violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)(2); lying to the FBI regarding his knowledge of a scheme in the Sheriff’s Department to intimidate an FBI agent who was investigating complaints of beatings of inmates by deputies at the LA County Jail, and to hide an FBI informant – jail inmate from his FBI handlers.

I. I Called The Police To Protect Me, So Why Was I The One Who Was Beaten-Up And Arrested?

A frequent type of case in which the police falsely arrest an innocent person, is when you, your spouse, your lover, or your parent or child, call the police. Many times family members feel that they cannot control mentally ill (or mad or drunk / drugged-up) people, including and especially their relatives, so they call “911″; often believing that the ambulance and paramedics are going to come to actually help them. They may not have even thought that the police would be the responding agency, but when they find out that the police are there, trouble may be awaiting. Once the cops are on the scene, they are taught to take charge, and anyone challenging, or even questioning, the police giving orders or their authority to do so, even seemingly unreasonable ones, is going to either get physically abused by the police, or falsely arrested by the police, or both.

members feel that they cannot control mentally ill (or mad or drunk / drugged-up) people, including and especially their relatives, so they call “911″; often believing that the ambulance and paramedics are going to come to actually help them. They may not have even thought that the police would be the responding agency, but when they find out that the police are there, trouble may be awaiting. Once the cops are on the scene, they are taught to take charge, and anyone challenging, or even questioning, the police giving orders or their authority to do so, even seemingly unreasonable ones, is going to either get physically abused by the police, or falsely arrested by the police, or both.

Also, many spouses or lovers call the police on each other, to get the other person out of  the house; even for a night or two. The police are not there to solve your family problems, so when you make that call, don’t make it unless you want your spouse or lover to go to jail, or worse. Cops are not counselors. They take people to jail. That’s what they do. So remember, when you call the police on your parent, child, lover or spouse, the person who ends-up getting thumped and arrested by the police just may be you. “No” you say? The police won’t arrest me if I’m the party calling the police. You’re wrong. They don’t care who called. All that the seem to care about, is how you respond to them; regardless of how unreasonable they act. If then, they thump you and beat you up, the odds are, that the police won’t even investigate the subject matter that you called about. Now, all of their attention is on you, since they violated you.

the house; even for a night or two. The police are not there to solve your family problems, so when you make that call, don’t make it unless you want your spouse or lover to go to jail, or worse. Cops are not counselors. They take people to jail. That’s what they do. So remember, when you call the police on your parent, child, lover or spouse, the person who ends-up getting thumped and arrested by the police just may be you. “No” you say? The police won’t arrest me if I’m the party calling the police. You’re wrong. They don’t care who called. All that the seem to care about, is how you respond to them; regardless of how unreasonable they act. If then, they thump you and beat you up, the odds are, that the police won’t even investigate the subject matter that you called about. Now, all of their attention is on you, since they violated you.

Also, do not use the police to get a border or a family member out of your house, unless the person is posing a “real” threat of imminent serious physical harm. If it’s that bad that you can’t stay in the house, then leave and get a hotel room, or just leave. The police cannot summarily evict / eject a civilian from a home in which they reside; whether they’re on the lease or not. In California, if a person resides at a home, only a Judge can force them to leave; either in the form of: 1) a Writ of Possession (the Court Order that the landlord gets in an “unlawful detainer” action, to give to the Sheriff’s Department, to eject you from your home, when you don’t pay your rent); 2) a Civil Harassment Restraining Order (under Cal. Civ. Proc. Code § 527.6); 3) a Domestic Violence Restraining Order (under Cal. Family Code § 6320), and 4) an Emergency Protective Order in a criminal case (pursuant to Cal. Penal Code § 136.2.)

II. Contempt Of Cop Cases – A Frequent Reason For False Arrests By Police Officers.

“Contempt Of Cop“ cases, are bogus criminal actions, brought against innocents by criminal prosecutors, for essentially, “bruised ego“ violations. The “ego bruising”, is really nothing more than a civilian not immediately, and without protest or question, getting-down on the ground in a proned position, or not doing something that the officer wants you to do (lawful, reasonable or not) immediately, and without question or protest. The Constable‘s “ego” is typically “bruised”, by your conduct, such as: 1) asserting your Constitutional rights, or 2) claiming knowledge of them, or 3) asking the Constable why you’re being ordered to lie down on the ground while your chest is being illuminated by the red spot of a pistol or rifle targeting device; 4) telling the Constable that you have a medical condition that makes it difficult or painful to get on the ground; 5) telling the Constable that he can’t do something (i.e. can’t go in my house without a warrant; you can’t make me go inside or come outside); 6) failing to consent to an entry or a search; and 7) not exiting your house when ordered to do so (even though the police generally can’t order you to exit a private residence; save probable cause to arrest for serious dangerous felony, coupled with an emergency; See, United States v. Al-Azzawy, 784 F.2d 890 (9th Cir. 1985) and Elder v. Holloway, 510 U.S. 510 (1994.) These are but a few examples. The list is endless, but the theme is the same. Failing to immediately do whatever the police tell you to do, without protest, challenge or remarks, often will result in your being beaten-up, falsely arrested, and maliciously criminally prosecuted.

These, “Contempt Of Cop” cases, typical involve the police using force upon persons (i.e. beating them) and/or falsely arresting them, and then inventing bogus allegations of violations various “Contempt Of Cop” statutes, such as violations of: 1) Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) (resisting / obstructing / delaying peace officer [commonly called “resisting arrest”]; the most abused statute in the Penal Code; 2) Cal. Penal Code § 240 /241(b) (assault on a peace officer); 3) Cal. Penal Code § 242 / 243(b) (battery on a peace officer); and 4) Cal. Penal Code 69 (interfering with public officer via actual or threatened use of force or violence.) Cal. Penal Code § 69 is a “wobbler“; a California public offense that may be filed by the District Attorney’s Office as either a felony or a misdemeanor. In Orange County, Riverside County and LA County, allegations of violation of Penal Code § 69 are usually filed as misdemeanors. In San Bernardino County, however, allegations of violation of Cal. Penal Code § 69 are filed as felonies much more often than her sister counties. If they shoot you, they may even charge you with Cal. Penal § Code 245(d); assault on a peace officer in a manner likely to result in great bodily injury.

III. Police Incompetence: A Frequent Reason For False Arrests By Police Officers.

Believe it or not, most experienced police officers have a pretty good functional understanding of very basic fourth amendment search and seizure issues. For example, police training about basic street contacts with civilians includes the following:

- Detentions of persons outside of the home;

- Arrests of persons outside of the home;

- The use of force on persons outside of the home;

- Probation searches

- Parole searches

- Search warrants

- Warrantless searches of persons, vehicles and homes

Once you get past the basics, most police officers really don’t understand what the Constitution forbids them from doing. Police officers simply are not sufficiently trained to properly act within with long established Constitutional constraints on them. It takes years for lawyers and judges to understand fourth amendment search and seizure issues, and they disagree often about whether certain conduct is, or is not, constitutional.

Moreover, just like the rest of us, the cops make mistakes all of the time. They are human, and, therefore, false arrests by police officers are almost very often the product of either sheer incompetence (i.e. the police arrest another for conduct that isn’t criminal), or of the police officer attempting to justify his unlawful conduct, by arresting and then framing their victim (i.e. false police reports, perjurious court testimony, false convictions) of his federal criminal (18 U.S.C. § 242), and otherwise tortious misconduct (i.e. if the police use unreasonable / unlawful force on a civilian, the use of force is almost always followed by a false arrest.)

FALSE ARREST CASES; CALIFORNIA LAW

FALSE ARREST BY PEACE OFFICER – ELEMENTS AND PROOF – CALIFORNIA LAW

A “false arrest” is the same “tort” as a “false imprisonment” under California law.  Unlike federal law, under California law, the burden is on the police to justify their “seizure” (false arrest / false imprisonment) of you at a civil trial (See, California Civil Jury Instructions (“CACI”) 1401 [False Arrest by Peace Officer Without Warrant] and 1402 [Peace Officer’s Justification / Defense To Claim Of False Arrest].) Under California law, a peace officer (i.e. police officer or deputy sheriff) may arrest another for a felony for which the officer has “probable cause” to believe person committed, or may arrest another for a misdemeanor that was committed in their presence (See, Cal. Penal Code § 836.) “Presence is not mere physical proximity but is determined by whether the offense is apparent to the officers senses. People v. Sjosten, 262 Cal.App.2d 539, 543544 (1968″.) An officer can arrest a civilian, upon probable cause, for any felony; committed in the presence of an officer or not. Cal. Penal Code § 836. However, it does not violate the fourth amendment, for an officer to arrest for a misdemeanor that was committed outside of the presence of the officer.

Unlike federal law, under California law, the burden is on the police to justify their “seizure” (false arrest / false imprisonment) of you at a civil trial (See, California Civil Jury Instructions (“CACI”) 1401 [False Arrest by Peace Officer Without Warrant] and 1402 [Peace Officer’s Justification / Defense To Claim Of False Arrest].) Under California law, a peace officer (i.e. police officer or deputy sheriff) may arrest another for a felony for which the officer has “probable cause” to believe person committed, or may arrest another for a misdemeanor that was committed in their presence (See, Cal. Penal Code § 836.) “Presence is not mere physical proximity but is determined by whether the offense is apparent to the officers senses. People v. Sjosten, 262 Cal.App.2d 539, 543544 (1968″.) An officer can arrest a civilian, upon probable cause, for any felony; committed in the presence of an officer or not. Cal. Penal Code § 836. However, it does not violate the fourth amendment, for an officer to arrest for a misdemeanor that was committed outside of the presence of the officer.

FALSE ARREST BY PEACE OFFICER – NO “QUASI-QUALIFIED IMMUNITY” – CALIFORNIA LAW

Cal. Penal Code 847(b) provides:

“There shall be no civil liability on the part of, and no cause of action shall arise against, any peace officer . . . acting within the scope of his or her authority, for false arrest or false imprisonment arising out of any arrest under any of the following circumstances:

(1) The arrest was lawful, or the peace officer, at the time of the arrest, had reasonable cause to believe the arrest was lawful.”

Although police civil defendants have argued that Section 847(b)(1) immunizes peace officers for false arrests like the “qualified immunity“ provided for police false arrest civil defendants federal court, that code section cannot be reasonably construed that way. The first part of Section 47(b)(1)(“The arrest was lawful”), logically changes nothing, for if the arrest was lawful, then there is no liability under anyone’s theory; kind an unintended legal redundancy. The second part of Section 47(b)(1) (“the peace officer, at the time of the arrest, had reasonable cause to believe the arrest was lawful”), could only reasonably be meant to apply to a situation, where an officer arrested a civilian based upon either: 1) an arrest warrant that did issue, but for which there was no probable cause to have issued (the officer who obtained the arrest warrant on insufficient grounds committed the fourth amendment violation, and is liable for the false arrest, unless otherwise protected, such as by “qualified immunity“), or 2) when the officer had “reasonable cause“, which is essentially a term equivalent to “probable cause” under the jury instructions that are used at the trial of this particular tort (See, CACI 1402; . . . arrest lawful if . . . “reasonable cause to believe that the plaintiff committed a crime“ is the standard for whether a peace officer’s arrest of a civilian was lawful.) Therefore, logically, Section 47(b)(1) provides no immunity for California peace officers for a false arrest. That does not mean, however, that a state or federal judge won’t disagree with that proposition. It is not fully developed under either California law, or by the federal district court’s interpretation of that statute.

FALSE ARREST BY PEACE OFFICER – FEDERAL LAW – GENERALLY

A “false arrest” under federal law, is considered a violation of a person’s right to be free from an “unreasonable seizure” of their person under the Fourth Amendment (See, Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Model Civil Jury Instruction for Arrest Without Probable Cause Or Warrant.) The United States Supreme Court has defined a “seizure of a person” as when a reasonable person would not feel free to leave the presence of police officers and to go about their business. See, United States v. Mendenhall, 446 U.S. 544 (1980.)

In 1871, Congress enacted the Ku Klux Klan Act (42 U.S.C. § 1983), that gives any person whose federal Constitutional rights have been violated, a right to sue, any person who violated those rights under the color of state law, in a United States District Court. Section 1983 lawsuits can also be brought in a state court of general jurisdiction; See, 42 U.S.C. § 1988. Accordingly, a person who is falsely arrested by a peace officer (i.e. police officer, deputy sheriff, or some other officer who derives peace officer powers from state law), may sue the police officer under Section 1983, as well as under California state law.

person whose federal Constitutional rights have been violated, a right to sue, any person who violated those rights under the color of state law, in a United States District Court. Section 1983 lawsuits can also be brought in a state court of general jurisdiction; See, 42 U.S.C. § 1988. Accordingly, a person who is falsely arrested by a peace officer (i.e. police officer, deputy sheriff, or some other officer who derives peace officer powers from state law), may sue the police officer under Section 1983, as well as under California state law.

In federal court, in a civil Fourth Amendment “arrest without probable cause” case (a federal false arrest case), the jury is instructed at the end of the case, on the following definition of “probable cause”:

“Probable cause exists when, under all of the circumstances known to the officer[s] at the time, an objectively reasonable police officer would conclude there is a fair probability that the plaintiff has committed or was committing a crime” (See, Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Model Civil Jury Instruction 9.20, Arrest Without Probable Cause Or Warrant.)

Therefore, that standard, whether “an objectively reasonable police officer would conclude there is a “fair probability” that the plaintiff has committed or was committing a crime”, is the standard that the propriety of an arrest, outside of the home is judged by, in federal court in the states comprising the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (Ninth Circuit Model Civil Jury Instruction 9.20). It doesn’t matter what the thousands of other cases, from the Supreme Court on down, say about what “probable cause” means. All that matters, is what a civil jury is going to be told is the standard that they should judge the facts by, in their deliberations (a civil jury is the “Judge of the facts” [“trier of fact”], and the District Judge is the “Judge of the law”.)

Some justices say that the words “probable cause“, are found in the text of the fourth amendment itself, and that is the standard for a seizure of a person by the government that was established by the Founding Fathers at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1791; not reasonable suspicion:

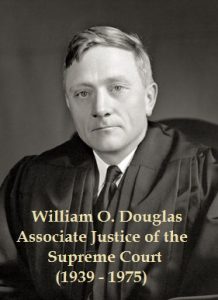

“MR. JUSTICE DOUGLAS, dissenting.

I agree that petitioner was “seized” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment. I also agree that frisking petitioner and his companions for guns was a “search.” But it is a mystery how that “search” and that “seizure” can be constitutional by Fourth Amendment standards unless there was “probable cause” [n1] to believe that (1) a crime had been committed or (2) a crime was in the process of being committed or (3) a crime was about to be committed.

The opinion of the Court disclaims the existence of “probable cause.” If loitering were in issue and that [p36] was the offense charged, there would be “probable cause” shown. But the crime here is carrying concealed weapons; [n2] and there is no basis for concluding that the officer had “probable cause” for believing that that crime was being committed. Had a warrant been sought, a magistrate would, therefore, have been unauthorized to issue one, for he can act only if there is a showing of “probable cause.” We hold today that the police have greater authority to make a “seizure” and conduct a “search” than a judge has to authorize such action. We have said precisely the opposite over and over again. [n3] [p37].”

In other words, police officers up to today have been permitted to effect arrests or searches without warrants only when the facts within their personal knowledge would satisfy the constitutional standard of probable cause. At the time of their “seizure” without a warrant, they must possess facts concerning the person arrested that would have satisfied a magistrate that “probable cause” was indeed present. The term “probable cause” rings a bell of certainty that is not sounded by phrases such as “reasonable suspicion.” Moreover, the meaning of “probable cause” is deeply imbedded in our constitutional history. As we stated in Henry v. United States, 361 U.S. 98, 100-102:

“The requirement of probable cause has roots that are deep in our history. The general warrant, in which the name of the person to be arrested was left blank, and the writs of  assistance, against which James Otis inveighed, both perpetuated the oppressive practice of allowing the police to arrest and search on suspicion. Police control took the place of judicial control, since no showing of “probable cause” before a magistrate was required.

assistance, against which James Otis inveighed, both perpetuated the oppressive practice of allowing the police to arrest and search on suspicion. Police control took the place of judicial control, since no showing of “probable cause” before a magistrate was required.

That philosophy [rebelling against these practices] later was reflected in the Fourth Amendment. And as the early American decisions both before and immediately after its adoption show, common rumor or report, suspicion, or even “strong reason to suspect” was not adequate to support a warrant [p38] for arrest. And that principle has survived to this day. . . .

. . . It is important, we think, that this requirement [of probable cause] be strictly enforced, for the standard set by the Constitution protects both the officer and the citizen. If the officer acts with probable cause, he is protected even though it turns out that the citizen is innocent. . . . And while a search without a warrant is, within limits, permissible if incident to a lawful arrest, if an arrest without a warrant is to support an incidental search, it must be made with probable cause. . . . This immunity of officers cannot fairly be enlarged without jeopardizing the privacy or security of the citizen.