Can You Sue The Police For Malicious Criminal Prosecutions?

By Jerry L. Steering, Esq.

The Short Answer is “No” Under California State Law, and “Yes” Under Federal Law.

![JLS in Courtroom]() California State Law Provides for Absolute Immunity for Any Public Employee Who Maliciously Prosecutes Another.

California State Law Provides for Absolute Immunity for Any Public Employee Who Maliciously Prosecutes Another.

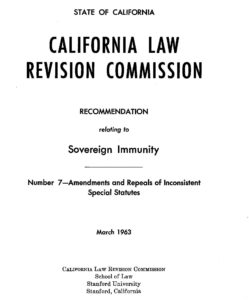

The California Law Review Commission was created by statute in 1953 to assist the Legislature and the Governor by examining California law and recommending needed reforms.

In 1963 the California Law Review Commission studied the then existing common law immunities for public employees, including judges, prosecutors and police officers (i.e. absolute Judicial Immunity, Stump v. Sparkman, 435 U.S. 349 (1978)), and absolute immunity for criminal prosecutors, Imbler v. Patchman, 424 U.S. 409 (1975) absolute prosecutorial immunity for filing and prosecuting any criminal action.

“Common law immunities”, are immunities enjoyed by usually governmental officials from claims or even lawsuits, that were “created” by judicial fiat; by the learned Judges of our state courts and of the federal bench. The word “common law” literally means judge made law.

In 1963, when codifying the then existing California common law immunities, when confronting the issue of whether a public employee (usually a police officer) should be liable for attempting to frame another, the California Law Review Commission recommended that there should be no such immunity:

“7. The immunity from liability for malicious prosecution that public employees now enjoy should be continued so that public officials will not be subject to harassment by “crank” suits. However, where public employees have acted maliciously in using their official powers, the injured person should not be totally without remedy. The employing public entity should, therefore, be liable for the damages caused by such abuse of public authority; and, in those cases where the responsible public employee acted with actual malice, the public entity should have the right to indemnity from the employee.” California Law Review Commission, Recommendation relating to Sovereign Immunity; Number 1-Tort Liability of Public Entities and Public Employees January 1963; p.817.

Contrary to that recommendation of the California Law Review Commission, that a person who is the victim of an attempted frame-up should have some legal remedy against the police officers attempting to frame them for a crime that they are not innocent of, the California legislature enacted Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6, that provides for absolute malicious prosecution immunity for any public employee, acting in the course and scope of their employment.

Contrary to that recommendation of the California Law Review Commission, that a person who is the victim of an attempted frame-up should have some legal remedy against the police officers attempting to frame them for a crime that they are not innocent of, the California legislature enacted Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6, that provides for absolute malicious prosecution immunity for any public employee, acting in the course and scope of their employment.

Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6 Provides:

“821.6. A public employee is not liable for injury caused by his instituting or prosecuting any judicial or administrative proceeding within the scope of his employment, even if he acts maliciously and without probable cause.”

This is simply malicious prosecution immunity under California state law for any public employee, including peace officers, acting in the course and scope of their employment. This section represents an exercise of “sovereign immunity“; “the King can do no wrong.” It is nothing sort of outrageous, and no decent society could defend such a law. Yet, since 1963 this has been the law in California.

Moreover, the California Courts have bent-over backwards to protect police officers from being liable for damages caused by their attempted framing of persons; including damages for innocents having to sit in jail on trumped-up charges that were almost always brought to justify the unjustified use of force upon a civilian. After all, how would it look if the police beat someone up and didn’t charge them with some “resistance offense”; some crime that places the blame for the officer’s use of force on the beating victim?

Frankly, this is outrageous, and downright un-American. It’s morally wrong (i.e. “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor”), it’s ethically wrong (what could be worse than framing your victim), and it simply should not be tolerated. However, the truth is that people in California are ignorant of most immunities that the law provides, and the police unions in Sacramento will never let the politicians do the right thing and repeal Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6.

The Police and The Prosecutors Maliciously Prosecute Innocent Victims Of Excessive Force and False Arrests to Protect the Police from Their Victims.

Malicious criminal prosecutions are the “first bite at the apple”, to preclude their innocent victims from suing them.

Even if you are somehow acquitted or otherwise beat the criminal case filed against you, the police still get to defend a civil action against de novo. A criminal conviction is only binding on the criminal defendant, but not the police. That’s why it’s the “first bite at the apple”. It the violating police officer’s first opportunity to preclude you from successfully suing him/her.

Moreover, even if there was no probable cause for your arrest, if you are convicted by way of a plea or verdict, as a policy matter, the U.S. Supreme Court has decided to preclude one convicted but still initially falsely arrested, from suing the police. See, Heck v. Humphrey, 512 U.S. 477 (1994) and the California Supreme Court has now adopted the Heck doctrine in Yount v. City of Sacramento, 43 Cal. 4th 885 (2008.)

In addition, if you are convicted of a “resistance offense” such as “resisting / obstructing / delaying peace officer (Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) (resisting / obstructing / delaying peace officer), or resisting peace officer with threat or use of force or violence (Cal. Penal Code § 69) or assault or battery on a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code § 240 / 241(c) & 245(c)) and Cal. Penal Code § 242 / 243(b) you now cannot sue the police for false arrest or excessive force, because an element of each of these “resistance offenses” is that the officer must have been engaged in the lawful performance of his/her duties. See, People v. Curtis, 70 Cal.2d 347 (1969).

Ergo, based on the doctrine of collateral estoppel, once an issue of fact has been determined against you in a prior judicial proceeding (i.e. a prior case), you cannot relitigate that issue in the subsequent proceeding; you are bound by the holding of the prior case. Therefore, if you are convicted of any crime, an element of which is that the police had to have been “engaged in the lawful performance of their duties”, you cannot thereafter sue the police for false arrest or excessive force.

Some people cannot afford to pay bail to fight their case, and will take a plea to get out of jail, even when they are totally innocent.

Some people do not want to pay for a lawyer and go through having to defend themselves on bogus resistance offense charges and will take a plea just to get the case over.

In addition, in most California counties, the District Attorney’s Office is more than happy to prosecute the innocent victim of police outrages, to beat them down and essentially force them to take some sort of plea agreement, to preclude the innocent person from suing the police for the outrages (usually excessive force) perpetrated against the innocent.

For example in MacDonald v. Musick, 425 F.2d 373 (9th Cir. 1970), Wendell MacDonald was arrested and prosecuted for driving under the influence of alcohol; a crime that he was apparently innocent of. Nonetheless the Orange County District Attorney’s Office filed the driving under the influence misdemeanor case based on the police report, but after reviewing the evidence, the District Attorney’s Office decided to dismiss the DUI case against Wendell MacDonald.

When the Court called the case, the District Attorney’s Office moved the Court to dismiss the case, and the Judge inquired whether Wendell MacDonald was going to stipulate that there was probable cause for his DUI arrest; something that would have precluded him from suing the arresting officer for false arrest.

When Wendell MacDonald’s lawyer to the Court “No”, that he would not stipulate that there was probable cause for his arrest, the District Attorney’s Office withdrew their request to dismiss the case, and moved the Court to amend the misdemeanor complaint to add a charge of resisting arrest; violation of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1).

In support of the motion for leave to amend the misdemeanor complaint to add the resisting arrest charge, the Deputy District Attorney said:

“Normally a defendant will stipulate to probable cause, and there is only one reason, let’s face it, for that stipulation, so that the defendant cannot sue the police department. This particular defendant would not stipulate to probable cause, which made it obvious, at least, there was an inference drawn, that perhaps here is a defendant that does have in mind suing the police department.” . . .

. . . “It seems to me that it is the duty of the Deputy District Attorney, in addition to prosecuting criminals, to protect the police officers, and in so protecting the police officers, it seems to me, after evaluating the facts, any Deputy District Attorney worth his salt would have at that point included any offense, obviously, in the report on which the defendant could have been convicted.”

The case then went to trial, and MacDonald was acquitted of DUI, but convicted of resisting arrest.

Although in a 2-1 Opinion the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the resisting arrest conviction should be reversed because it was brought to prevent MacDonald from suing the police, a violation of his First Amendment right to petition the government for redress of grievances, the attitude expressed by the prosecutor in that case remains a true today as it did in 1970. Prosecutors want to protect the police from you.

Federal Malicious Prosecution Law From 1994 to 2024.

U.S. Supreme Court Jurisprudence as a Constitutional Violation.

All of us understand that police officers framing people for crimes that they did not commit is about as evil as government officers can be. However, whether and what the Justices on the Supreme Court have decided to do something to remedy that obvious evil is a twisted tale indeed.

The Supreme Court’s First Opinion on Malicious Criminal Prosecution as a Constitutional Violation; Albright v. Oliver.

In Albright v. Oliver, 510 U.S. 266 (1994), upon learning that Illinois authorities had issued an arrest warrant charging Kevin Albright with the sale of a substance which looked like an illegal drug, he surrendered to respondent Roger Oliver, a policeman, and was released from jail after posting bail.

At a preliminary hearing, Officer Oliver testified that Albright sold the look-alike substance to a third party, and the court found probable cause to bind Albright over for trial. However, the court later dismissed the action on the ground that the charge did not state an offense under Illinois state law.

Kevin Albright then filed this suit under 42 U. S. C. § 1983, alleging that Roger Oliver deprived him of “substantive due process under the Fourteenth Amendment” – his “liberty interest” to be free from criminal prosecution except upon probable cause. The District Court dismissed on the ground that the complaint did not state a claim under § 1983. The United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit affirmed, holding that prosecution without probable cause is a constitutional tort actionable under § 1983 only if accompanied by incarceration, loss of employment, or some other “palpable consequence[e].”

Albright believed that the statute of limitations had run out of his false arrest claim, so he made no claim for violation of his Fourth Amendment rights via 42 U. S. C. § 1983 (the KKK Act of 1871) for his false arrest. As the Justices commented throughout their various Opinions in the Albright case, the outcome would have been different had Albright made a Fourth Amendment claim, but he did not do so based upon a misunderstanding of when the applicable statute of limitations precluded him from doing so.

In a 4-3-2 Plurality Opinion, Chief Justice Rehnquist, joined by Justice O’Connor, Justice Scalia and Justice Ginsberg, concluded that Albright’s claimed right to be free from prosecution without probable cause must be judged under the Fourth Amendment, rather than Fourteenth Amendment substantive due process, with its “scarce and open-ended” “guideposts for responsible decision making,”, and as Albright made no Fourth Amendment claim, that he was entitled to no relief under 42 U. S. C. § 1983.

Justice Scalia joined in the judgment because he wholly rejects the doctrine of substantive due process at all and, because he claimed that the injury suffered by Albright was the arrest, giving no credence to the notion that being falsely charged with a crime is injury in itself.

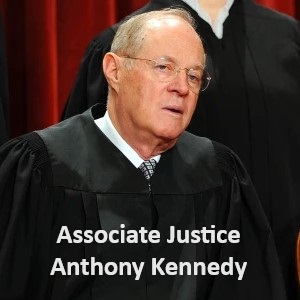

Justice Kennedy, joined by Justice Thomas, held that “. . . if a State did not provide a tort remedy for malicious prosecution, there would be force to the argument that the malicious initiation of a baseless criminal prosecution infringes an interest protected by the Due Process Clause and enforceable under § 1983.”

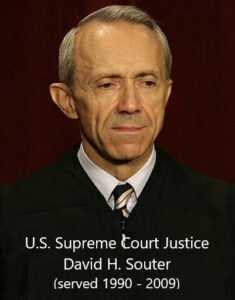

Justice Souter held that because Kevin Albright’s injuries emanated from his arrest and the Indictment that followed that arrest three days later, that his remedy lay under Fourth Amendment protections:

. . . it is not surprising that rules of recovery for such harms have naturally coalesced under the Fourth Amendment, since the injuries usually occur only after an arrest or other Fourth Amendment seizure, an event that normally follows promptly (3 days in this case) upon the formality of filing an indictment, information, or complaint. There is no restraint on movement until a seizure occurs or bond terms are imposed. Damage to reputation and all of its attendant harms also tend to show up after arrest. The defendant’s mental anguish (whether premised on reputational harm, burden of defending, incarceration, or some other consequence of prosecution) customarily will not arise before an arrest, or at least before the notification that an arrest warrant has been issued informs him of the charges.

There may indeed be exceptional cases where some quantum of harm occurs in the interim period after groundless criminal charges are filed but before any Fourth Amendment seizure. Whether any such unusual case may reveal a substantial deprivation of liberty, and so justify a court in resting compensation on a want of government power or a limitation of it independent of the Fourth Amendment, are issues to be faced only when they arise. They do not arise in this case and I accordingly concur in the judgment of the Court.

Justice Kennedy also concurred in the judgment, but for other reasons. He held that Fourth Amendment protections only protected persons from unlawful seizures of their persons, but not the prosecution of baseless criminal charges, and, therefore, the Fourth Amendment provided no remedy under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for Albright’s claim.

Moreover, Justice Kennedy went on to hold that under the Parratt Doctrine (Parratt v. Taylor, 451 U.S. 527 (1981)) if Illinois state law did not provide Albright an adequate tort remedy for his baseless/malicious criminal prosecution, that he would indeed most likely have a claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for violation of his substantive due process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. However, as Illinois state law did provide such a tort remedy for his baseless/malicious criminal prosecution, that Albright was not entitled to recover under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

“I agree with the plurality that an allegation of arrest without probable cause must be analyzed under the Fourth Amendment without reference to more general considerations of due process. But I write because Albright’s due process claim concerns not his arrest but instead the malicious initiation of a baseless criminal prosecution against him.” . . .

“. . . if a State did not provide a tort remedy for malicious prosecution, there would be force to the argument that the malicious initiation of a baseless criminal prosecution infringes an interest protected by the Due Process Clause and enforceable under § 1983 [citation omitted]. But given the state tort remedy, we need not conduct that inquiry in this case.”

Moreover, Justice Kennedy went on to hold that under the Parratt Doctrine (Parratt v. Taylor, 451 U.S. 527 (1981)) if Illinois state law did not provide Albright an adequate tort remedy for his baseless/malicious criminal prosecution, that he would indeed most likely have a claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for violation of his substantive due process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. However, as Illinois state law did provide such a tort remedy for his baseless/malicious criminal prosecution, that Albright was not entitled to recover under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

That said, if a State did not provide a tort remedy for malicious prosecution, there would be force to the argument that the malicious initiation of a baseless criminal prosecution infringes an interest protected by the Due Process Clause and enforceable under § 1983.

Accordingly, as discussed above, as California Government Code Section 821.6 provides absolute immunity for any California public employee acting in the course and scope of their employment from liability for any malicious criminal prosecution caused by them, that is, California does not provide an adequate tort remedy for malicious prosecution by public employees, under Justice Kennedy’s analysis, a malicious criminal prosecution by a California peace officer should be actionable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Interestingly, as Justice Thomas Joined in Justice Kennedy’s Opinion, one would think that Justice Thomas would also now support a Fourteenth Amendment basis for a malicious prosecution claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

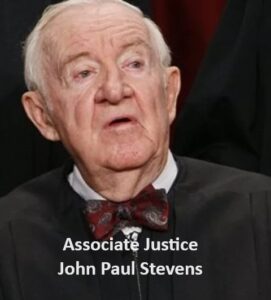

The Dissenting Opinion in Albright v. Oliver, authored by Justice Stevens, Joined by Justice Blackman, rejected the flawed reasoning of the other seven Justices, and simply held that if the Fourteenth Amendment protects anything, it certainly protects against the government framing innocent persons for crimes that the government knows that they did not commit:

“[T]he full scope of the liberty guaranteed by the Due Process Clause cannot be found in or limited by the precise terms of the specific guarantees elsewhere provided in the Constitution. This `liberty’ is not a series of isolated points pricked out in terms of the taking of property; the freedom of speech, press, and religion; the right to keep and bear arms; the freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures; and so on. It is a rational continuum which, broadly speaking, includes a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions and purposeless restraints . . . and which also recognizes, what a reasonable and sensitive judgment must, that certain interests require particularly careful scrutiny of the state needs asserted to justify their abridgment.” Poe v. Ullman, 367 U.S. 497, 543 (1961) (dissenting opinion).

I have no doubt that an official accusation of an infamous crime constitutes a deprivation of liberty worthy of constitutional protection. The Framers of the Bill of Rights so concluded, and there is no reason to believe that the sponsors of the Fourteenth Amendment held a different view. The Due Process Clause of that Amendment should therefore be construed to require a responsible determination of probable cause before such a deprivation is effected.”

If there is anything that would constitute what the courts call substantive due process (i.e. outrageous police conduct that shocks the conscience), attempting to frame an innocent is it. However, although the Supreme Court could not agree on whether a malicious criminal prosecution was a substantive due process violation in Albright v. Oliver, the Justices did not want to leave one who the police attempted to frame without a remedy. They left open a Fourth Amendment path to remedy a malicious criminal prosecution, and, as shown below, has reaffirmed that path to redress for malicious prosecutions.

Accordingly, the moral of the story from Albright v. Oliver, 510 U.S. 266 (1994) is that unless the state does not provide an adequate tort remedy for a malicious criminal prosecution, an innocent person who the police attempted to frame for a crime that they did not commit, can sue under the Fourth Amendment via 42 U.S.C. § 1983; if at least as at some point in time, they were subjected to an arrest / incarceration of their person that led up to their malicious criminal prosecution, and probably even if they weren’t. In reality, these words were crafted by the Supreme Court to permit persons who are falsely and maliciously accused of a crime by the police that resulted in a bogus criminal prosecution, to sue the police who attempted to frame them. It’s judicial “newspeak“.

Malicious Prosecution Cases in Federal Court in California Following Albright v. Oliver.

Ninth Circuit Malicious Prosecution Jurisprudence Before Albright v. Oliver; Some Other Constitutional Right or No Adequate State Law Tort Remedy.

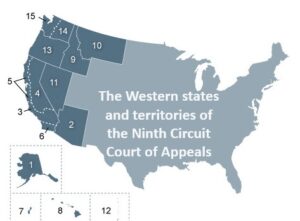

Prior to Albright v. Oliver in 1994, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (any place in the United States west of Nevada) rule on malicious prosecutions was that although a naked malicious prosecution claim was not actionable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, that one way or another, they would somehow permit a malicious prosecution plaintiff to sue anyway.

Twenty years before Albright v. Oliver (in 1994) the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that a malicious civil administrative proceeding in which plaintiff Paskaly ultimately prevailed on in a state court proceeding following an adverse ruling in an administrative hearing did not constitute a substantive due process violation, because Paskaly ultimately won his case in Court, and because a malicious prosecution of a civil action or even of a bogus criminal action against an innocent did not constitute a deprivation of life, liberty or property without due process of law and, therefore, is not cognizable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983″:

Twenty years before Albright v. Oliver (in 1994) the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that a malicious civil administrative proceeding in which plaintiff Paskaly ultimately prevailed on in a state court proceeding following an adverse ruling in an administrative hearing did not constitute a substantive due process violation, because Paskaly ultimately won his case in Court, and because a malicious prosecution of a civil action or even of a bogus criminal action against an innocent did not constitute a deprivation of life, liberty or property without due process of law and, therefore, is not cognizable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983″:

“Paskaly likens the proceedings to which he was subjected to the tort of malicious prosecution. Malicious prosecution, however, is a concept applicable only in criminal proceedings. See Nesmith v. Alford, 318 F.2d 110, 121 (5th Cir. 1963). Moreover, the tort of malicious prosecution, without more, does not constitute a civil rights violation. Martin v. King, 417 F.2d 458, 462 (10th Cir. 1969); Curry v. Ragan, 257 F.2d 449, 450 (5th Cir. 1958); Lyons v. Baker, 180 F.2d 893 (5th Cir. 1950). In addition, under the facts, Seale is not responsible for the bringing of the civil action. See note 2, supra.

Absent some showing of a violation of the Equal Protection Clause, or the impairment of some other specific constitutional safeguard, grievances of this nature are not covered by the sanctions of the Civil Rights Acts. See Curry v. Ragan, 257 F.2d 449, 450 (5th Cir. 1958).”

Paskaly v. Seale 506 F.2d 1209, 1212-1213, (9th Cir. 1974).

See also, Cline v. Brusett, 661 F.2d 108, 112 (9th Cir. 1981). However, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals also held that a naked claim for malicious prosecution was actionable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, if the state did not provide an adequate tort remedy for a malicious prosecution (i.e. immunity for the police), or if the malicious prosecution was brought to deprive the malicious prosecution plaintiff of some other constitutional right. Cline v. Brusett, 661 F.2d 108, 112 (9th Cir. 1981).

Malicious Prosecution Claims via Violation of Some Other Constitutional Right.

In Usher v. City of Los Angeles, 828 F.2d 556 (9th Cir. 1987), Sterling Usher, a black African-American claimed that LAPD officers beat and falsely arrested him while calling him a ni___er and a coon, and thereafter procured his bogus malicious criminal prosecution.

Usher sued the LAPD officers under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for false arrest, excessive force and malicious prosecution, also claiming that they did these things to him due to racial animus, in violation of his rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals allowed Usher to sue for his beating, his false arrest and for his malicious criminal prosecution on the ground that the constitutional torts perpetrated against him were at least in part motivated by racial animus:

“In this circuit, the general rule is that a claim of malicious prosecution is not cognizable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 if process is available within the state judicial system to provide a remedy. Bretz v. Kelman, 73 F.2d 1026, 1031 (9th Cir. 1985) (en banc); Cline v. Brusett, 661 F.2d 108, 112 (9th Cir. 1981). However, “an exception exists to the general rule when a malicious prosecution is conducted with the intent to deprive a person of equal protection of the laws or is otherwise intended to subject a person to a denial of constitutional rights.” Bretz, 773 F.2d at 1031; Cline, 661 F.2d at 112. In California, the elements of malicious prosecution are (1) the initiation of criminal prosecution, (2) malicious motivation, and (3) lack of probable cause. Singleton v. Perry, 45 Cal. 2d 489, 494, 289 P.2d 794 (1955); see 4 B. Witkin, Summary of California Law, Torts Secs. 242, 245-53 (8th ed. 1974).”

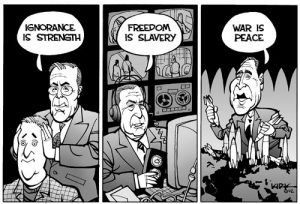

This take on a malicious prosecution being actionable if brought to deprive other of some other constitutional right, is frankly, nonsense; judicial “Orwellian Newspeak“.

This take on a malicious prosecution being actionable if brought to deprive other of some other constitutional right, is frankly, nonsense; judicial “Orwellian Newspeak“.

Imagine police officer (“acting under the color of state law“) tells material lies to the local District Attorney’s Office and falsely and maliciously procures one’s bogus criminal prosecution to retaliate against one for say, protected criticism of a government official; say for a civilian saying f__k you to the officer; something that the courts have held is protected free speech under the First Amendment (See, Duran v. City of Douglas, 904 F.2d 1372 (9th Cir. 1990).)

Or, imagine that a police officer hits another with the officer’s Billy Club, to retaliate against another for say, for a civilian flipping-off the officer; again, hitting the speaker with the officer’s Billy Club was merely the adverse action done in retaliation for the exercise of protected free speech under the First Amendment.

Both the procurement of the bogus criminal charges and the hitting the civilian with the Billy Club are retaliatory acts done in violation of the First Amendment free-speech rights of the civilian who cussed-out the police officer. There is no need to characterize the false procurement of the bogus criminal charges as anything other than the adverse action taken against the civilian for flipping-off the cop, just like hitting the civilian with the Billy Club. They are both First Amendment retaliation actions and are both actionable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 under a First Amendment retaliation theory.

There is no need to provide a separate claim for malicious prosecution, as the attempt to frame the innocent civilian is simply the Billy Club or the hammer, or whatever other form of adverse actions done by the officer in retaliation for protected speech. Ergo, the Ninth Circuit’s rule that a malicious prosecution is actionable if brought to deprive one of some other constitutional right is wholly unnecessary.

The attempted framing of the innocent is nothing more than the adverse action that violates that other constitutional right. Logically, there is no need to characterize the adverse action (i.e. attempting framing of an innocent) as anything other than a violation of that other constitutional right.

Malicious Prosecution Claims via No Adequate Tort Remedy in California.

As shown above, 20 years before the Supreme Court’s Plurality Opinion in Albright v. Oliver in 1994, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that if the state did not provide an adequate tort remedy to allow the victim of an attempted police frame-up to sue for their malicious criminal prosecution, that the malicious prosecution victim would have a viable claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983:

“We have held that malicious prosecution generally does not constitute a deprivation of liberty without due process of law and is not a federal constitutional tort if process is available within the state judicial systems to remedy such wrongs. Cline v. Brusett, 661 F.2d 108, 112 (9th Cir. 1981).”

As shown above, Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6 provides absolute immunity for a malicious prosecution by any public employee for actions done in the course and scope of their employment. Therefore, under this reasoning, a malicious prosecution in California should be actionable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 because of Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6 immunity.

However, no Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals case has ever held that Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6 immunity allowed a Section 1983 plaintiff to sue for malicious prosecution in a particular case; even after the U.S. Supreme Court issued its opinion six months after Cline v. Brusett, was decided in Parratt v. Taylor, 451 U.S. 527 (1981) (holding that the deprivation of liberty or property by the state constitutes a 14th Amendment substantive due process violation if there is no adequate state tort remedy for the deprivation).

When It Comes to Suing the Police for Malicious Prosecutions, the Ninth Circuit Case Law On Malicious Prosecutions Isn’t What it Says, But What it Does.

The law isn’t what it says, but what it does. The law is what happens to real people in the real world.

In the real world, there really is no law per se, and there never has been; in the United States or in any other country. Same for the United States Constitution. It has never been anything other than what the Supreme Court said it was. Almost all federal constitutional law is made up by the Supreme Court and the federal Circuit Courts. If you have any doubts about that proposition, just read some U.S. Supreme Court Opinions, and you will have no doubt that it’s all made up; all of it. See U.S. Supreme Court Opinions at Opinions of the Court – 2023 (supremecourt.gov).

Notwithstanding the Ninth Circuit’s jurisprudence on malicious prosecution claims, the Ninth Circuit nonetheless has allowed one to sue the police for their attempted frame-up of him/her by characterizing the effort to frame another as the proximate result of a false arrest, coupled with the arresting officer (and often others) authoring bogus police reports to falsely convict the malicious prosecution victim.

Federal Judges do not want the police to be able to attempt to falsely convict innocents, and notwithstanding Ninth Circuit proclamations that attempted frame-ups do not constitute constitutional violations upon which one can sue under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, prior to Albright v. Oliver in 1994, one could do so anyway, so long as they could prove that the decision to prosecute the innocent was not the product of the independent judgment of the Deputy District Attorney who filed and prosecuted the criminal action complained of. See, Smiddy v. Varney, 665 F.2d 261 (9th Cir. 1981), cert. denied, 459 U.S. 829 (1982) (Smiddy I), and Smiddy v. Varney, 803 F.2d 1469 (9th. Cir 1985) (Smiddy II).

The (Smiddy I) and (Smiddy II) cases held that one arrested and thereafter criminally prosecuted, can sue and collect damages under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 against the police officers who falsely and maliciously procured their bogus criminal prosecution, so long as they could rebut the presumption that the prosecuting District Attorney did not use their independent judgment in deciding to prosecute the innocent. That presumption can be rebutted by either showing that the police made false material representations of facts upon which the District Attorney relied in deciding to prosecute the innocent, or, that the police exerted pressure on the District Attorney that badgered or coerced them to abandon their independent judgment and prosecute someone who they had no reason to believe was guilty.

Ninth Circuit Malicious Prosecution Jurisprudence After Albright v. Oliver; Fourth Amendment Basis for Malicious Criminal Prosecutions.

Although the Plurality Opinion in Albright v. Oliver held that a malicious criminal prosecution did not constitute such outrageous and conscience shocking behavior as to constitute a substantive due process violation under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (frankly, a ridiculous holding), the majority of the Justices also held that if the state did not provide an adequate tort remedy for a malicious criminal prosecution, the innocent falsely prosecuted person could sue under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for their attempted frame-up.

The majority of Justices in Albright v. Oliver’s 4-3-2 Opinion also held that a malicious criminal prosecution might be characterized as a Fourth Amendment unreasonable seizure violation that was actionable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

Following that pronouncement in Albright v. Oliver, in Galbraith v. County of Santa Clara, 307 F.3d 1119 (9th Cir. 2002) the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that a malicious criminal prosecution was a naked constitutional tort; a Fourth Amendment violation, actionable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

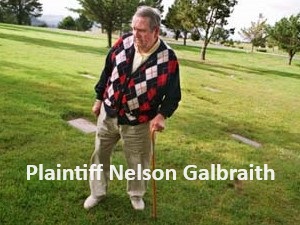

In Galbraith v. County of Santa Clara a Santa Clara County autopsy surgeon who originally ruled a death was a suicide, changed his medical forensic opinion, and claimed that his examination of the decedent’s neck showed strangulation. On the basis of that changed opinion, the local police had Galbraith arrested and prosecuted for murder. He was ultimately acquitted and sued the autopsy surgeon and Santa Clara County for his false arrest and his malicious prosecution, claiming that the autopsy surgeon never did examine the neck bones, and fabricated his opinion to frame Galbraith.

In Galbraith v. County of Santa Clara a Santa Clara County autopsy surgeon who originally ruled a death was a suicide, changed his medical forensic opinion, and claimed that his examination of the decedent’s neck showed strangulation. On the basis of that changed opinion, the local police had Galbraith arrested and prosecuted for murder. He was ultimately acquitted and sued the autopsy surgeon and Santa Clara County for his false arrest and his malicious prosecution, claiming that the autopsy surgeon never did examine the neck bones, and fabricated his opinion to frame Galbraith.

Regarding the constitutional provision that Galbraith could sue under via 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for his malicious criminal prosecution, the Ninth Circuit held:

“. . . we agree, without deciding any issue of immunity, that a coroner’s reckless or intentional falsification of an autopsy report that plays a material role in the false arrest and prosecution of an individual can support a claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and the Fourth Amendment. See Cabrera v. City of Huntington Park, 159 F.3d 374 (9th Cir. 1998) (analyzing claims of false arrest and malicious prosecution under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and the Fourth Amendment). . .

. . . We agree with the district court, however, that Fourth Amendment principles, and not those of due process, govern this case. See County of Sacramento v. Lewis, 523 U.S. 833, 843, 118 S.Ct. 1708, 140 L.Ed.2d 1043 (1998) (discussing Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 109 S.Ct. 1865, 104 L.Ed.2d 443 (1989)). The Fourth Amendment addresses “pretrial deprivations of liberty,” Albright v. Oliver, 510 U.S. 266, 274, 114 S.Ct. 807, 127 L.Ed.2d 114 (1994) (plurality opinion), also at issue here, so “[the Fourth] Amendment, not the more generalized notion of ‘substantive due process,’ must be the guide for analyzing these claims.” Id. at 273, 114 S.Ct. 807 (quoting Graham, 490 U.S. at 395, 109 S.Ct. 1865); see also id. at 276-77, 114 S.Ct. 807 (Ginsburg, J., concurring). The dismissal of the due process claims was therefore correct.”

Galbraith v. County of Santa Clara, 307 F.3d 1119 (9th Cir. 2002).

Two years later, the Ninth Circuit also continued its pre-Galbraith malicious prosecution jurisprudence and held that in addition to constituting a Fourth Amendment violation, one could sue for a malicious criminal prosecution if the prosecution was brought to deprive the innocent of some other constitutional right, such as attempting to frame an innocent in retaliation for protected exercise of First Amendment free speech, or, as a naked constitutional tort. See, Awabdy v. City of Adelanto, 368 F.3d 1062, 1069–72 (9th Cir. 2004.)

In reality, these words were crafted by the Supreme Court to permit persons who are falsely and maliciously accused of a crime by the police that resulted in a bogus criminal prosecution, to sue the police who attempted to frame them. It’s judicial “newspeak“.

If there is anything that would constitute what the courts call substantive due process (i.e. outrageous police conduct that shocks the conscience), attempting to frame an innocent is it. However, the Supreme Court could not agree on whether a malicious criminal prosecution was a substantive due process violation in Albright v. Oliver, but the Justices did not want to leave one who the police attempted to frame without a remedy.

U.S. Supreme Court Malicious Prosecution Jurisprudence After Albright v. Oliver; Fourth Amendment Basis for Malicious Criminal Prosecutions.

Implicit Recognition of a Fourth Amendment Basis for a Malicious Prosecution Claim; Manuel v. City of Joliet.

In Manuel v. City, of Joliett, 580 U.S. _____ (2017), the Supreme Court held that one who was physically arrested and confined in custody by way of the false arrest of a police officer, can obtain damages under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for that person’s continued confinement in jail, after the point in time when the District Attorney (prosecutor) formally filed criminal charges against the person. In other words, the accused person can collect damages for being kept in jail before trial, pursuant to criminal charges, filed by the prosecutor, that were procured by the arresting police officer having authored a false police report, that the prosecutor relied upon in deciding to file the very criminal charges that kept the false accused person in jail before trial.

Manuel v. City, of Joliett, implicitly provided for malicious prosecution claims, without explicitly declaring that a malicious criminal prosecution claim was viable as a distinct constitutional tort, at least when there was the arrest and incarceration of the plaintiff. However, this still didn’t declare a Naked Constitutional Tort of a Malicious Criminal Prosecution; only a damages remedy for a false arrest, and for confinement in jail after the point in time when the prosecutor formally filed criminal charges against the confined person; the equivalent of a Fourth Amendment malicious prosecution claim.

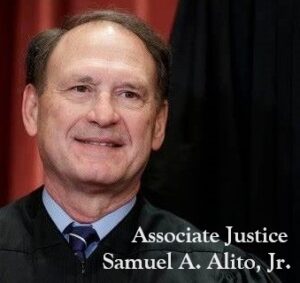

In Justice Alito’s Dissenting Opinion in Manuel v. City, of Joliett, (joined by Justice Thomas), he agreed with allowing one incarcerated past the point in time when the District Attorney filed criminal charges to obtain damages for that continued incarceration, due to the prosecution, maliciously and falsely procured by the police. However, Justice Alito remarked that the Majority Opinion never squarely addressed the Question Presented to the Supreme Court to decide:

“I agree with the Court’s holding up to a point: The protection provided by the Fourth Amendment continues to apply after “the start of legal process,” ante, at 1, if legal process is understood to mean the issuance of an arrest warrant or what is called a “first appearance” under Illinois law and an “initial appearance” under federal law. Ill. Comp. Stat., ch. 725, §§5/109–1(a), (e) (West Supp. 2015); Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 5. But if the Court means more—specifically, that new Fourth Amendment claims continue to accrue as long as pretrial detention lasts—the Court stretches the concept of a seizure much too far.

What is perhaps most remarkable about the Court’s approach is that it entirely ignores the question that we agreed to decide, i.e., whether a claim of malicious prosecution may be brought under the Fourth Amendment. I would decide that question and hold that the Fourth Amendment cannot house any such claim. If a malicious prosecution claim may be brought under the Constitution, it must find some other home, presumably the Due Process Clause.”

Manuel v. City, of Joliett, Alito, J., Dissenting.

Following both Albright v. Oliver and Manuel v. City of Joliet, most United States District Courts and the United States Courts of Appeals (the federal intermediate level appellate courts) permitted a Section 1983 remedy for a malicious criminal prosecution by a peace officer, regardless of whether the malicious prosecution plaintiff had been arrested, incarcerated or otherwise “seized” at all.

The First, Second and Eleventh Circuits composed the “Tort Circuits,” wherein plaintiffs pleading malicious prosecution claims under Section 1983, were required to satisfy the common law elements of a malicious prosecution claim in addition to proving a constitutional violation. The “Constitutional Circuits”—the Fourth, Fifth, Seventh, and Tenth — concentrated on whether a constitutional violation exists.

Most of the Circuits of the United States Courts of Appeals, allowed for an aggrieved person the right to sue for being subjected to a malicious criminal prosecution, federal remedy for the same, via 42 U.S.C. § 1983. They did so, on various theories, since the right to be free from a malicious criminal prosecution is not described in the federal Constitution, but the pure evil and outrageousness of such government action compels appellate judges to find some Constitutional foundation for that right, in order to allow a person who the government attempted to frame, some sort of remedy.

Although sister circuits categorized the Third Circuit as a “Tort Circuit”, the Third Circuit more recently acknowledged that “[o]ur law on this issue is unclear”; however, it continued to encourage plaintiffs to address each common law element. Similarly, the Sixth Circuit has avoided defining the required elements of a claim, although it appears to recognize a Fourth Amendment right against malicious prosecution and continued detention without probable cause. The Ninth Circuit lies on both sides of the divide; seemingly turning on whether they want the malicious prosecution plaintiff to prevail.

Federal Law Now Clearly Provides a Remedy For a Malicious Criminal Prosecution, Usually As Long As the Malicious Prosecution Plaintiff Shows that At Some Point in Time, He Was “Seized”.

Thompson v. Clark Changed the “Favorable Termination” Element of a Malicious Prosecution Claim For All Of The Federal Courts.

In Thompson v. Clark, 596 U.S. _______ (April 4, 2022) the U.S. Supreme Court held for the first time that there is a Constitutional Tort of Malicious Criminal Prosecution; at least under a Fourth Amendment theory, where at some point during the series of events involved in the case, the malicious prosecution plaintiff was deemed to have been “seized” at some point in time, such as an arrest or actual incarceration, even for a brief period of time. Thompson v. Clark, 596 U.S. _______ (April 4, 2022) didn’t expressly rely on whether the malicious prosecution plaintiff had been “seized” (i.e. arrested or jailed) for some period of time, as Thomas had been arrested.

Thompson v. Clark also changed the “favorable termination” element of a malicious prosecution claim for all of the federal courts.

Prior to Thompson v. Clark a malicious prosecution claim brought in federal court within the territorial jurisdiction of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (i.e. any place West of Utah) could only be successful, if, in addition to the other elements of malicious prosecution (1) procurement of criminal case by the police, 2) without probable cause, and 3) with malice), the underlying criminal action was terminated in a manner inconsistent with guilt:

“A favorable termination must reflect the merits of the action and the malicious prosecution plaintiff’s innocence of the misconduct alleged therein. Id. “If [the termination] is of such a nature as to indicate the innocence of the accused, it is a favorable termination sufficient to satisfy the requirement. If, however, the dismissal is on technical grounds, for procedural reasons, or for any other reason not inconsistent with his guilt, it does not constitute a favorable termination.”

Now, under Thompson v. Clark, in order to sue for a malicious criminal prosecution under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, the “favorable termination” element of a malicious prosecution claim only require that the underlying criminal prosecution did not result in a conviction:

“In sum, we hold that a Fourth Amendment claim under §1983 for malicious prosecution does not require the plaintiff to show that the criminal prosecution ended with some affirmative indication of innocence. A plaintiff need only show that the criminal prosecution ended without a conviction.”

This dramatically changed the “favorable termination” requirement for a federal malicious claim in at least California, that held that the termination of the underlying criminal case had to be done in a manner, inconsistent with guilt, and could not be the product of compromise.

Moreover, in a footnote, the Majority in Thompson v. Clark also held that a malicious prosecution claim that did not involve the arrest or confinement, however brief, may not fall under the Fourth Amendment, but rather under the protections of substantive due process under the Fourteenth Amendment:

“Because this claim is housed in the Fourth Amendment, the plaintiff also has to prove that the malicious prosecution resulted in a seizure of the plaintiff. See Manuel v. Joliet, 580 U.S. 357, 365–366 (2017). It has been argued that the Due Process Clause could be an appropriate analytical home for a malicious prosecution claim under §1983. See Albright v. Oliver, 510 U.S. 266, 281, 286 (1994) (Kennedy, J., concurring in judgment). If so, the plaintiff presumably would not have to prove that he was seized as a result of the malicious prosecution. But we have no occasion to consider such an argument here.”

Interestingly, in his Dissenting Opinion, Justice Alito sees the Majority Opinion in Thompson v. Clark as creating a naked constitutional tort of malicious prosecution, that he claims is made out of thin air, without precedent, and should more logically been seen as be that a substantive due process under the Fourteenth Amendment, at least of the state in which the claim arose did not provide an adequate tort remedy.

Accordingly, it now seems to be the case that if a malicious prosecution of one takes place in California, either under a Fourth Amendment “unreasonable seizure” theory, or a substantive due process analysis (as California has not adequate state law tort remedy for malicious prosecutions due to Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6), an innocent subjected to a malicious prosecution can sue those who without probable cause, maliciously procured their bogus criminal prosecution that did not result in a conviction.

The Supreme Court Unexpectedly Increases the Scope of Potential Malicious Prosecution Cases in Ciaverini v. City of Napoleon.

In Ciaverini v. City of Napoleon, ____ U.S. ______ (June 20, 2024), the U.S. Supreme Court held that even if the police have probable cause to arrest and prosecute one for a particular crime, if they falsely and maliciously procure the prosecution of one for a crime that they did not commit, and for which the police did not have probable cause to believe one committed.

As Justice Kagan held:

“The presence of probable cause for one charge in a criminal proceeding does not categorically defeat a Fourth Amendment malicious prosecution claim relating to another, baseless charge.”

” This Court has analogized claims like Chiaverini’s to the common-law tort of malicious prosecution, and has explained that the tort can inform courts’ understanding of this type of claim. Thompson v. Clark, 596 U. S. 36, 43–44. A plaintiff bringing a common-law malicious-prosecution suit had to show that an official initiated a charge without probable cause. But he did not have to show that every charge brought against him lacked an adequate basis.”

Ciaverini v. City of Napoleon, ____ U.S. ______ (June 20, 2024), Kagan, J.

However, Justice Kagan’s Majority Opinion is premised on a Fourth Amendment basis for malicious criminal prosecutions, based on continued pre-trial detention based upon the prosecution for offenses that the police had no probable cause to believe the malicious prosecution plaintiff guilty of.

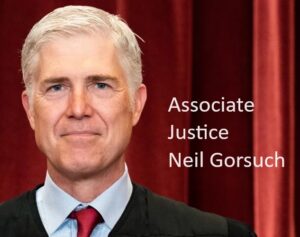

Interestingly, in Justice Gorsuch’s Dissenting Opinion, he shed a large ray of light on a malicious prosecution claim where no “seizure” of the malicious prosecution plaintiff had occurred, and the malicious prosecution claim was only based on having to defend oneself in court, without ever having been arrested or jailed. Justice Gorsuch basically stated that such a seizureless malicious prosecution claim should fall within the ambit of the Fourteenth Amendment’s “procedural” due process protections if the state did not provide an adequate tort remedy for such malicious prosecution claims:

“The Fourth Amendment addresses the permissibility of a seizure. But a common-law malicious-pros

ecution claim can (and usually does) proceed without one. Ante, at 2–3. A seizure in violation of the Fourth Amend ment can (and often does) take place without the initiation of any judicial process. But the whole point of a malicious prosecution claim is to contest the appropriateness of past judicial proceedings. Ante, at 2. For all these reasons, it’s “pretty hard to see how you might squeeze anything that looks quite like the common law tort of malicious prosecution into the Fourth Amendment.” Cordova, 816 F. 3d, at 663 (opinion of Gorsuch, J.).That is not to say no constitutional hook exists for a §1983 claim addressing the malicious use of process. Rather, it seems to me only that such a claim would be more properly housed in the Fourteenth Amendment. See Albright, 510 U. S., at 283 (opinion of Kennedy, J.). After all, unlike the

Fourth Amendment, that provision does focus on judicial proceedings, guaranteeing those who come before our courts “due process” of law. See ibid.; Thompson, 596 U. S., at 43, n. 2; Cordova, 816 F. 3d, at 662 (opinion of Gorsuch, J.). Inhering in due process is a promise that courts will respect, at the least, those “customary procedures to which freemen were entitled by the old law of England.” Sessions v. Dimaya, 584 U. S. 148, 176 (2018) (GORSUCH, J., concurring in part and concurring in judgment) (internal quotation marks omitted). And the common law has long recognized a tort of malicious prosecution to protect against the abuse of judicial proceedings. Albright, 510 U. S., at 283 (opinion of Kennedy, J.).Admittedly, a procedural due process claim for malicious prosecution may come with its own set of limitations. After all, when a State provides exactly the tort claim the plaintiff seeks, it provides him with all the process he is due. See id., at 284; Cordova, 816 F. 3d, at 662 (opinion of Gorsuch, J.). And, consistent with the common law, many States recognize claims for malicious prosecution. Indeed,

the relevant State here (Ohio) permits such a cause of action. Notably, too, unlike the tort this Court seeks to cobble together under the aegis of the Fourth Amendment, Ohio’s tort does not require a plaintiff to prove that he was seized. Compare Trussell v. General Motors Corp., 53 Ohio St. 3d 142, 145–146, 559 N. E. 2d 732, 735–736 (1990), with ante, at 1 (majority opinion). Of course, should a State fail to provide a malicious-prosecution claim to secure his procedural due process rights, or a fair forum for entertaining such a claim, a federal court may need to act to vindicate §1983 and the promise of procedural due process. Cordova, 816 F. 3d, at 665 (opinion of Gorsuch, J.). But in many

cases (this one included), a State malicious-prosecution claim may be both easier for a plaintiff to prove than any thing the Court today provides and sufficient to ensure any process he is due. Albright, 510 U. S., at 285–286 (opinion of Kennedy, J.); Cordova, 816 F. 3d, at 662 (opinion of Gorsuch, J.).For these reasons, I respectfully dissent.”

Ciaverini v. City of Napoleon, ____ U.S. ______ (June 20, 2024), Gorsuch, J., Dissenting

Summary

As things stand today, if a police officer procures your malicious criminal prosecution in California, if you were “seized” at some point in time in the series of events that culminated or resulted from your malicious prosecution, you have a Fourth Amendment Malicious Prosecution claim under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for your bogus criminal prosecution, even if one or more of the charges filed against you was legitimate, so long as one or more was not.

However, from 1994 in Albright v. Oliver to 2024 in Ciaverini v. City of Napoleon, the Supreme Court has shown that if the state does not provide an adequate tort remedy for a malicious prosecution that had never been initiated or resulted in the seizure or confinement of the plaintiff, then the Supreme Court recognizes a Procedural or Substantive Due Process Claim under the Fourteenth Amendment.

Because as shown above, California immunizes all public employees, especially the police, from suit for a malicious prosecution via Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6, if you have been maliciously prosecuted, you almost assuredly have a remedy under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for your bogus criminal prosecution.

If you have questions about malicious criminal prosecutions and whether you have a viable malicious prosecution case, please contact the Law Office of Jerry L. Steering for a free telephone consultation.

Good luck,

Jerry L. Steering, Esq.

The Law Offices of Jerry L. Steering, 4063 Birch Street, Suite 100, Newport Beach, CA 92660, 949-474-1849, (Fax) 949-474-1883, jerry@steeringlaw.com

California State Law Provides for Absolute Immunity for Any Public Employee Who Maliciously Prosecutes Another.

California State Law Provides for Absolute Immunity for Any Public Employee Who Maliciously Prosecutes Another. . . . it is not surprising that rules of recovery for such harms have naturally coalesced under the Fourth Amendment, since the injuries usually occur only after an arrest or other

. . . it is not surprising that rules of recovery for such harms have naturally coalesced under the Fourth Amendment, since the injuries usually occur only after an arrest or other  “I agree with the plurality that an allegation of arrest without probable cause must be analyzed under the

“I agree with the plurality that an allegation of arrest without probable cause must be analyzed under the  “[T]he full scope of the liberty guaranteed by the Due Process Clause cannot be found in or limited by the precise terms of the specific guarantees elsewhere provided in the Constitution. This `liberty’ is not a series of isolated points pricked out in terms of the taking of property; the freedom of speech, press, and religion; the right to keep and bear arms; the freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures; and so on. It is a rational continuum which, broadly speaking, includes a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions and purposeless restraints . . . and which also recognizes, what a reasonable and sensitive judgment must, that certain interests require particularly careful scrutiny of the state needs asserted to justify their abridgment.” Poe v. Ullman,

“[T]he full scope of the liberty guaranteed by the Due Process Clause cannot be found in or limited by the precise terms of the specific guarantees elsewhere provided in the Constitution. This `liberty’ is not a series of isolated points pricked out in terms of the taking of property; the freedom of speech, press, and religion; the right to keep and bear arms; the freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures; and so on. It is a rational continuum which, broadly speaking, includes a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions and purposeless restraints . . . and which also recognizes, what a reasonable and sensitive judgment must, that certain interests require particularly careful scrutiny of the state needs asserted to justify their abridgment.” Poe v. Ullman,  “I agree with the Court’s holding up to a point: The protection provided by the Fourth Amendment continues to apply after “the start of legal process,” ante, at 1, if legal process is understood to mean the issuance of an arrest warrant or what is called a “first appearance” under Illinois law and an “initial appearance” under federal law. Ill. Comp. Stat., ch. 725, §§5/109–1(a), (e) (West Supp. 2015); Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 5. But if the Court means more—specifically, that new Fourth Amendment claims continue to accrue as long as pretrial detention lasts—the Court stretches the concept of a seizure much too far.

“I agree with the Court’s holding up to a point: The protection provided by the Fourth Amendment continues to apply after “the start of legal process,” ante, at 1, if legal process is understood to mean the issuance of an arrest warrant or what is called a “first appearance” under Illinois law and an “initial appearance” under federal law. Ill. Comp. Stat., ch. 725, §§5/109–1(a), (e) (West Supp. 2015); Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 5. But if the Court means more—specifically, that new Fourth Amendment claims continue to accrue as long as pretrial detention lasts—the Court stretches the concept of a seizure much too far. “The presence of probable cause for one charge in a criminal proceeding does not categorically defeat a Fourth Amendment malicious prosecution claim relating to another, baseless charge.”

“The presence of probable cause for one charge in a criminal proceeding does not categorically defeat a Fourth Amendment malicious prosecution claim relating to another, baseless charge.” “The Fourth Amendment addresses the permissibility of a seizure. But a common-law malicious-pros

“The Fourth Amendment addresses the permissibility of a seizure. But a common-law malicious-pros