![JLS DATELINE AT DESK FROM RIGHT FRONT]() IS IT A CRIME TO REFUSE TO IDENTIFY YOURSELF TO A POLICE OFFICER IN CALIFORNIA?

IS IT A CRIME TO REFUSE TO IDENTIFY YOURSELF TO A POLICE OFFICER IN CALIFORNIA?

The California courts have long held that a person may not be arrested for failure to identify him/herself, other than when he/she has been lawfully arrested and refuses to identify him/herself while going through the booking process. See, In Re Gregory S., 112 Cal.App.3d 764 (1980) (failure to identify self to peace officer not crime in California); People v. Quiroga, 16 Cal.App.4th 961, 970 (1993) (failure to identify self in booking process may be a violation of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1), but merely failure to identify self prior to booking not a crime); People v. Christopher, 137 Cal.App.4th 418 (2006) (same); In re Chase C., Cal.App.4th (2015) (failure to identify self to peace officer not violation of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1)).

However, if you are arrested for violation of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) (resisting / obstructing / delaying peace officer’s performance of duties), depending on the circumstances, you may not be able to successfully sue for such an arrest in federal court due to a 2022 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals case that questioned all of the published California Court of Appeals cases on that issue, See, Vanegas v. City of Pasadena, No. 21-55478 (9th Cir. August 31, 2022).

HIIBEL v. SIXTH JUDICIAL DISTRICT HELD THAT A STATE CAN CRIMINALIZE A PERSON’S FAILURE TO IDENTIFY THEMSELVES TO A POLICE OFFICER.

In Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial Dist. Court of Nev., 542 U.S. 177 (2004) the U.S. Supreme Court held that a person does not have a Fifth Amendment right to refuse to identify himself to a police officer, that if the state has a stop and identify statute, that a state can criminalize a person’s failure to identify himself to a police officer. However, for the time being Hiibel did not change longstanding California appellate caselaw that held that it is not a crime in California to refuse to identify oneself to a police officer, save when one is in jail and being booked.

In Brown v. Texas, 443 U.S. 47 (1979) the U.S. Supreme Court. Brown overturned a conviction under a Texas “stop and identify” law similar to that at issue in Hiibel. Id. at 49–50. Unlike Hiibel, Brown was stopped, detained, and interrogated about his identity even though there was no reasonable suspicion that he had committed any offense. Brown v. Texas held squarely that law enforcement may not require a person to furnish identification if not reasonably suspected of any criminal conduct. In short, Brown v. Texas holds that an officer may not lawfully order a person to identify herself absent particularized suspicion that she has engaged, is engaging, or is about to engage in criminal activity, and Hiibel does not hold to the contrary.

Hiibel was predicated on a Nevada “stop and identify” statute (N.R.S. 171.123), and California does not have such a statute. In the absence of a specific “stop and identify” statute, the Ninth Circuit has held that “use of Section 148 to arrest a person for refusing to identify herself during a lawful Terry stop violates the Fourth Amendment’s proscription against unreasonable searches and seizures.” Martinelli v. City of Beaumont, 820 F.2d 1491, 1494 (9th Cir. 1987).

In Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial Dist. Court of Nev., 542 U.S. 177 (2004) the U.S. Supreme Court held that a person does not have a Fifth Amendment right to refuse to identify himself to a police officer, that if the state has a stop and identify statute, that a state can criminalize a person’s failure to identify himself to a police officer. However, for the time being Hiibel did not change longstanding California appellate caselaw that held that it is not a crime in California to refuse to identify oneself to a police officer, save when one is in jail and being booked.

In Brown v. Texas, 443 U.S. 47 (1979) the U.S. Supreme Court. Brown overturned a conviction under a Texas “stop and identify” law similar to that at issue in Hiibel. Id. at 49–50. Unlike Hiibel, Brown was stopped, detained, and interrogated about his identity even though there was no reasonable suspicion that he had committed any offense. Brown v. Texas held squarely that law enforcement may not require a person to furnish identification if not reasonably suspected of any criminal conduct. In short, Brown v. Texas holds that an officer may not lawfully order a person to identify herself absent particularized suspicion that she has engaged, is engaging, or is about to engage in criminal activity, and Hiibel does not hold to the contrary.

Hiibel was predicated on a Nevada “stop and identify” statute (N.R.S. 171.123), and California does not have such a statute. In the absence of a specific “stop and identify” statute, the Ninth Circuit has held that “use of Section 148 to arrest a person for refusing to identify herself during a lawful Terry stop violates the Fourth Amendment’s proscription against unreasonable searches and seizures.” Martinelli v. City of Beaumont, 820 F.2d 1491, 1494 (9th Cir. 1987).

Arizona has a similar “stop and identify statute. See, Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-2412(A) (“It is unlawful for a person, after being advised that the person’s refusal to answer is unlawful, to fail or refuse to state the person’s true full name on request of a peace officer who has lawfully detained the person based on reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing or is about to commit a crime.”)

In Martinelli, officers who suspected that Martinelli was involved in a hit-and-run collision approached her and asked her for identification. Id. at 1492. Martinelli refused to identify herself to officers for over 30 minutes, then walked away. Ibid. Officers arrested Martinelli under California Penal Code section 148 “for delaying a lawful police investigation by refusing to identify herself.” Ibid. Relying on vagueness analysis in Lawson v. Kolender, 658 F.2d 1362 (9th Cir.1981), aff’d., 461 U.S. 352 (1983), the court held that “use of Section 148 to arrest a person for refusing to identify herself during a lawful Terry stop violates the Fourth Amendment’s proscription against unreasonable searches and seizures.” Id. at 1494.

Arizona has a similar “stop and identify statute. See, Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-2412(A) (“It is unlawful for a person, after being advised that the person’s refusal to answer is unlawful, to fail or refuse to state the person’s true full name on request of a peace officer who has lawfully detained the person based on reasonable suspicion that the person has committed, is committing or is about to commit a crime.”)

In Martinelli, officers who suspected that Martinelli was involved in a hit-and-run collision approached her and asked her for identification. Id. at 1492. Martinelli refused to identify herself to officers for over 30 minutes, then walked away. Ibid. Officers arrested Martinelli under California Penal Code section 148 “for delaying a lawful police investigation by refusing to identify herself.” Ibid. Relying on vagueness analysis in Lawson v. Kolender, 658 F.2d 1362 (9th Cir.1981), aff’d., 461 U.S. 352 (1983), the court held that “use of Section 148 to arrest a person for refusing to identify herself during a lawful Terry stop violates the Fourth Amendment’s proscription against unreasonable searches and seizures.” Id. at 1494.

The California Department of Justice has acknowledged that Hiibel does not provide a basis for arrest under Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) where detainees refuse to provide identifying information to police officers.

Moreover, Martinelli may still be binding law even in the wake of Hiibel. Contrary to defendants’ claim that Martinelli was “no longer good law in the wake of Hiibel ,” Hiibel merely upheld a Nevada “stop and identify” statute (N.R.S. 171.123) which specifically authorized arrests of lawfully detained persons who refused to identify themselves. Hiibel , 542 U.S. at 188.

The Hiibel court also clarified its holding, so as not to confuse officers in defendants’ position: “the source of the legal obligation arises from Nevada state law, not the Fourth Amendment.” Id. at 187 (emphasis added). However, as shown below, again, depending on the Judge that you have and the circumstances of your case, in light of Vanegas v. City of Pasadena, No. 21-55478 (9th Cir. 2022), even if the Judge in your case determines that you were unlawfully arrested for failing to identify yourself, the defendant peace officers may still prevail under the Doctrine of Qualified Immunity. See, A Practical Cure for the Curse of Qualified Immunity, steeringlaw.com.

The California Department of Justice has acknowledged that Hiibel does not provide a basis for arrest under Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) where detainees refuse to provide identifying information to police officers.

Moreover, Martinelli may still be binding law even in the wake of Hiibel. Contrary to defendants’ claim that Martinelli was “no longer good law in the wake of Hiibel ,” Hiibel merely upheld a Nevada “stop and identify” statute (N.R.S. 171.123) which specifically authorized arrests of lawfully detained persons who refused to identify themselves. Hiibel , 542 U.S. at 188.

The Hiibel court also clarified its holding, so as not to confuse officers in defendants’ position: “the source of the legal obligation arises from Nevada state law, not the Fourth Amendment.” Id. at 187 (emphasis added). However, as shown below, again, depending on the Judge that you have and the circumstances of your case, in light of Vanegas v. City of Pasadena, No. 21-55478 (9th Cir. 2022), even if the Judge in your case determines that you were unlawfully arrested for failing to identify yourself, the defendant peace officers may still prevail under the Doctrine of Qualified Immunity. See, A Practical Cure for the Curse of Qualified Immunity, steeringlaw.com.

JUST BECAUSE IT’S NOT A CRIME DOESN’T MEAN THAT THE POLICE WILL NOT ARREST YOU FOR COMMITTING IT.

The police admit but spin what they can’t deny (i.e. conclusive video or audio recording), and deny anything prejudicial, or any material fact that is viewed as potentially helpful to the victim of police abuse being able to recover compensation for outrages perpetrated upon them.

A recent example of the ignorance about and misuse of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) is the arrest of actress Daniele Watts in Los Angeles by the LAPD.

The LAPD received a call that a man and a woman were getting it on in a car in Los Angeles. When they arrived at the scene they saw Daniel Watts and her boyfriend, but they weren’t doing anything. The LAPD Officer started his investigation for a possible case of lewd conduct in public (Cal. Penal Code § 647(a)) and asked Ms. Watts for her name. She refused to tell the officer her name, claiming that she had a right not to do so. Notwithstanding the fact that Ms. Watt’s claim was correct, the LAPD Officer told her that she had no such right and that she was obligated to divulge her identity to him (which is not the law.) Because of Ms. Watts’ refusal to identify herself, the LAPD Officer handcuffed her and placed her in the back seat of his patrol car.

Throughout the contact, one can hear the officer repeat that he had “probable cause” (of some crime; which he didn’t), and that when the police are investigating a crime that a civilian has a duty to cooperate with the police including having to tell the police who they are, under the threat of arrest for non-compliance for Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1). The officer was wrong on both counts. First, a person has no obligation to cooperate with a police investigation; especially of themselves. See, People v. Shelton, 60 Cal.2d 740 (1964) (“A suspect has no duty to cooperate with officers in securing evidence against him“.)

Second, since 1980 the California Courts have held that it is not a crime for a person to refuse to identify themselves to the police; even if they’re being lawful detained (save when they’re at the jail and are being booked) See, In re Chase C., Cal.App.4 (12/18/15); In re Gregory S.,112 Cal. App. 3d 764, 779 (1980); People v. Quiroga, 16 Cal.App.4th 961 (1993); People v. Christopher, 137 Cal.App.4th 418 (2006); United States v. Christian, 356 F.3d 1103 (9th Cir. 2004); Martinelli v. City of Beaumont, 820 F.2d 1491 (9th Cir. 1987).

The police admit but spin what they can’t deny (i.e. conclusive video or audio recording), and deny anything prejudicial, or any material fact that is viewed as potentially helpful to the victim of police abuse being able to recover compensation for outrages perpetrated upon them.

A recent example of the ignorance about and misuse of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) is the arrest of actress Daniele Watts in Los Angeles by the LAPD.

The LAPD received a call that a man and a woman were getting it on in a car in Los Angeles. When they arrived at the scene they saw Daniel Watts and her boyfriend, but they weren’t doing anything. The LAPD Officer started his investigation for a possible case of lewd conduct in public (Cal. Penal Code § 647(a)) and asked Ms. Watts for her name. She refused to tell the officer her name, claiming that she had a right not to do so. Notwithstanding the fact that Ms. Watt’s claim was correct, the LAPD Officer told her that she had no such right and that she was obligated to divulge her identity to him (which is not the law.) Because of Ms. Watts’ refusal to identify herself, the LAPD Officer handcuffed her and placed her in the back seat of his patrol car.

Throughout the contact, one can hear the officer repeat that he had “probable cause” (of some crime; which he didn’t), and that when the police are investigating a crime that a civilian has a duty to cooperate with the police including having to tell the police who they are, under the threat of arrest for non-compliance for Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1). The officer was wrong on both counts. First, a person has no obligation to cooperate with a police investigation; especially of themselves. See, People v. Shelton, 60 Cal.2d 740 (1964) (“A suspect has no duty to cooperate with officers in securing evidence against him“.)

Second, since 1980 the California Courts have held that it is not a crime for a person to refuse to identify themselves to the police; even if they’re being lawful detained (save when they’re at the jail and are being booked) See, In re Chase C., Cal.App.4 (12/18/15); In re Gregory S.,112 Cal. App. 3d 764, 779 (1980); People v. Quiroga, 16 Cal.App.4th 961 (1993); People v. Christopher, 137 Cal.App.4th 418 (2006); United States v. Christian, 356 F.3d 1103 (9th Cir. 2004); Martinelli v. City of Beaumont, 820 F.2d 1491 (9th Cir. 1987).

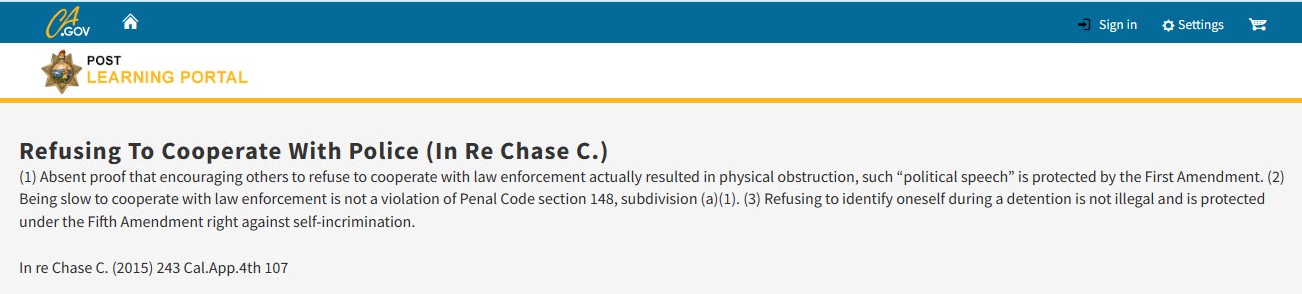

So, while LAPD Chief Charlie Beck was on radio and television defending his officer’s arrest of Ms. Watts for refusing to divulge her name (See KCAL 9 TV Broadcast), he was encouraging other LAPD officers to commit crimes against civilians like the LAPD officer did against Ms. Watts when he cuffed her and placed her in his car for violation of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) for failing to identify herself. That’s a federal crime by the LAPD Officer; a violation of federal constitutional rights under color of authority; 18 U.S.C. § 242; a felony. Fear not, however, Chief Beck; the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office has now come to your rescue. The California District Attorney’s Association and the California Department of Justice has even published guidance for California Peace Officers on this issue, and that guidance is that a failure to identify oneself to a peace officer is not a crime in California:

So, while LAPD Chief Charlie Beck was on radio and television defending his officer’s arrest of Ms. Watts for refusing to divulge her name (See KCAL 9 TV Broadcast), he was encouraging other LAPD officers to commit crimes against civilians like the LAPD officer did against Ms. Watts when he cuffed her and placed her in his car for violation of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) for failing to identify herself. That’s a federal crime by the LAPD Officer; a violation of federal constitutional rights under color of authority; 18 U.S.C. § 242; a felony. Fear not, however, Chief Beck; the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office has now come to your rescue. The California District Attorney’s Association and the California Department of Justice has even published guidance for California Peace Officers on this issue, and that guidance is that a failure to identify oneself to a peace officer is not a crime in California:

“The U.S. Supreme Court has drawn a distinction between a detainee’s duty to identify himself and his duty to answer non-identification questions during a lawful detention. In Berkemer (1984) 468 U.S. 420, 439, the court stated that a detainee is not obligated to answer any questions you put to him during a lawful detention. However, in Hiibel, the Supreme Court clarified that it was not referring in Berkemer to questions regarding identity. The Court upheld as constitutional a Nevada “stop and identify” statute and found that a detainee’s failure to identify himself could be the basis for a lawful arrest under a companion statute almost identical to Penal Code section 148. (Hiibel (2004) 124 S.Ct. 2451.) Unlike Nevada and other states, California does not have a statute mandating that a detainee identify himself, and that obligation cannot be read into Penal Code section 148. Although you may take whatever steps are reasonably necessary under the circumstances to ascertain the identity of a person you have lawfully detained, Hiibel does not provide a means for arresting someone for failing or refusing to identify himself. The Ninth Circuit has ruled that a suspect’s failure to identify himself cannot, on its own, justify an arrest: “the use of Section 148 to arrest a person for refusing to identify herself during a lawful Terry stop violates the Fourth Amendment’s proscription against unreasonable searches and seizures.” (Martinelli (9th Cir.1987) 820 F.2d 1491, 1494; Christian (9th Cir.2004) 356 F.3d 1103, 1106.)” See, California Department of Justice and California District Attorneys Association, 2012 Field Guide to the California Peace Officers Legal Sourcebook § 2.13-2.14a (Rev. Jan. 2012).See also, the California Department of Justice Peace Officer Standards on Training webpage on this issue, that shows:

Notwithstanding this clear pronouncement of the reach and ambit of Section 148(a)(1), specifically, that it does not criminalize a person’s failure to identify himself to a peace officer, even if the officer is lawfully detaining him/her, apparently out of pure political defiance, the Los Angeles Police Department actually directs its police officer to ignore the California Department of Justice and the California District Attorney’s Association on that issue. The LAPD publishes a bulletin to it’s officer, telling that that it’s a crime for a lawfully detained civilian to fail to identify himself to a peace officer.

Moreover, to make matters worse, the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office eventually filed criminal charges against Miss Watts for lewd conduct in public, but not for the crime that she was initially seized for; violation of Section 148(a)(1.) She ultimately pleaded guilty to disturbing the peace; a de minimis misdemeanor, and received a fine; precluding her for suing the officer for arresting her for a crime that she was innocent of. This is pure politics, of the worst sort.

Notwithstanding this clear pronouncement of the reach and ambit of Section 148(a)(1), specifically, that it does not criminalize a person’s failure to identify himself to a peace officer, even if the officer is lawfully detaining him/her, apparently out of pure political defiance, the Los Angeles Police Department actually directs its police officer to ignore the California Department of Justice and the California District Attorney’s Association on that issue. The LAPD publishes a bulletin to it’s officer, telling that that it’s a crime for a lawfully detained civilian to fail to identify himself to a peace officer.

Moreover, to make matters worse, the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office eventually filed criminal charges against Miss Watts for lewd conduct in public, but not for the crime that she was initially seized for; violation of Section 148(a)(1.) She ultimately pleaded guilty to disturbing the peace; a de minimis misdemeanor, and received a fine; precluding her for suing the officer for arresting her for a crime that she was innocent of. This is pure politics, of the worst sort.

The District Attorney’s Office knows that Miss Watts didn’t violate Section 148(a)(1); (the crime that Miss Watts was handcuffed and placed in the police car for, and they knew that the ACLU had been discussing Miss Watts’ options with her. Nonetheless, the DA’s office came to the rescue of the LAPD officers, by obtaining a conviction of her (guilty plea bargain) for disturbing the peace; a de minimis misdemeanor. She was never charged with violation of Section 148(a)(1); the charge that she was arrest for violating. However, because the Supreme Court has decreed that as a matter of “public policy”, that if you’re convicted of anything, anything, that you can’t sue the arresting officer.

So, if the officer arrested you for murder, and you were required to post $1,000,000.00 bail, if a reasonably well trained officer would have had probable cause to arrest you for anything that the laws proscribes (i.e. seal belt violation), then you can’t sue the officer for false arrest; even if he/she didn’t have a clue that your conduct constituted a violation of some other criminal / vehicle statute. See, When v. United States, 517 U.S. 806 (1996) (standard for propriety of arrest by peace officer is the ”reasonably well trained officer in the abstract”; officer’s subject motive for search or seizure irrelevant to determination of fourth amendment violation.)

The District Attorney’s Office knows that Miss Watts didn’t violate Section 148(a)(1); (the crime that Miss Watts was handcuffed and placed in the police car for, and they knew that the ACLU had been discussing Miss Watts’ options with her. Nonetheless, the DA’s office came to the rescue of the LAPD officers, by obtaining a conviction of her (guilty plea bargain) for disturbing the peace; a de minimis misdemeanor. She was never charged with violation of Section 148(a)(1); the charge that she was arrest for violating. However, because the Supreme Court has decreed that as a matter of “public policy”, that if you’re convicted of anything, anything, that you can’t sue the arresting officer.

So, if the officer arrested you for murder, and you were required to post $1,000,000.00 bail, if a reasonably well trained officer would have had probable cause to arrest you for anything that the laws proscribes (i.e. seal belt violation), then you can’t sue the officer for false arrest; even if he/she didn’t have a clue that your conduct constituted a violation of some other criminal / vehicle statute. See, When v. United States, 517 U.S. 806 (1996) (standard for propriety of arrest by peace officer is the ”reasonably well trained officer in the abstract”; officer’s subject motive for search or seizure irrelevant to determination of fourth amendment violation.)

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN SUING THE POLICE FOR VIOLATION OF CAL. PENAL CODE SECTION 148(a)(1) FOR FAILING TO IDENTIFY ONESELF TO A PEACE OFFICER DURING DETENTION.

Notwithstanding the above and foregoing authorities that uniformly have held that it is not a crime in California to fail to identify oneself to a peace officer when being lawfully detained, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has recently held that a California peace officer may not be civilly liable for damages to a person that he/she arrested for just that reason. On August 31, 2022 the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit awarded a Pasadena, California police officer qualified immunity from suit for arresting one Javier Vanegas for violation of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) for, you guessed it, failing to identify himself while being lawfully detained by a Pasadena Police Department police officer. See, Vanegas v. City of Pasadena, No. 21-55478 (9th Cir. August 31, 2022): “No “controlling authority” or “robust consensus of cases” prohibited Officer Klotz from arresting Vanegas under the facts confronting him. Wesby, 138 S. Ct. at 589 (simplified). Neither this court nor the Supreme Court has said that arresting a person for failing to provide an identification violates the Constitution. In fact, we have both said the opposite. See Hiibel v. Sixth Jud. Dist. of Humboldt Cnty., 542 U.S. 177, 187–88 (2004) (upholding a state law permitting arrest for failure to identify oneself—where the request for identification is reasonably related to circumstances justifying the stop—as “consistent with Fourth Amendment prohibitions against unreasonable searches and seizures”); United States v. Landeros, 913 F.3d 862, 869 (9th Cir. 2019) (“In some circumstances, a suspect may be required to respond to an officer’s request to identify herself, and may be arrested if she does not.”).

“No “controlling authority” or “robust consensus of cases” prohibited Officer Klotz from arresting Vanegas under the facts confronting him. Wesby, 138 S. Ct. at 589 (simplified). Neither this court nor the Supreme Court has said that arresting a person for failing to provide an identification violates the Constitution. In fact, we have both said the opposite. See Hiibel v. Sixth Jud. Dist. of Humboldt Cnty., 542 U.S. 177, 187–88 (2004) (upholding a state law permitting arrest for failure to identify oneself—where the request for identification is reasonably related to circumstances justifying the stop—as “consistent with Fourth Amendment prohibitions against unreasonable searches and seizures”); United States v. Landeros, 913 F.3d 862, 869 (9th Cir. 2019) (“In some circumstances, a suspect may be required to respond to an officer’s request to identify herself, and may be arrested if she does not.”).

And no California case clearly establishes that Officer Klotz should have known he lacked probable cause to arrest Vanegas for failing to identify himself in the course of the stalking investigation. Indeed, multiple district courts, including the one here, thought Officer Klotz could make the arrest. See Nakamura v. City of Hermosa Beach, 2009 WL 1445400, at *8 (C.D. Cal. 2009); Abdel-Shafy v. City of San Jose, 2019 WL 570759, at *7 (N.D. Cal. 2019); Vanegas v. City of Pasadena, 2021 WL 1917126, at *6 (C.D. Cal. 2021). And so did we. See Kuhlken v. Cnty. of San Diego, 764 F. App’x 612 (9th Cir. 2019).

Thus, even if Vanegas’s failure to identify himself did not provide probable cause to arrest under § 148(a)(1)—a question we need not and do not decide—Officer Klotz had “breathing room” to make the purported mistake of law and he and the other officers are entitled to qualified immunity for Vanegas’s arrest.

BUMATAY, Circuit Judge”

Even following Vanegas v. City of Pasadena, No. 21-55478 (9th Cir. August 31, 2022) California police agencies still advise their officers that other than a person’s refusal to identify oneself while going through the booking process at a jail or prison, a California peace officer may not arrest a person for violation of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1) for failing to identify themselves to a peace officer (i.e. police officer or deputy sheriff). See for example, Ventura County Community College District Police Department, Training Outline, Failure To Identify (“During a lawful legal detention, an officer has the right to request or demand the detained person provide identification. However, an officer cannot arrest the detained person for failure to identify under Penal Code Section 148(a)(1)“). Accordingly, notwithstanding a plethora of California Court of Appeal cases holding for many years now that it is not a crime in California for one to refuse or fail to identify oneself to a peace officer when being lawfully detained, under present Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals case law, one may not be able to successfully sue a peace officer for arresting one for doing just that, in light of the Vanegas Opinion. Jerry L. Steering, Esq. FREE CASE EVALUATION

FREE CASE EVALUATION

IS IT A CRIME TO REFUSE TO IDENTIFY YOURSELF TO A POLICE OFFICER IN CALIFORNIA?

IS IT A CRIME TO REFUSE TO IDENTIFY YOURSELF TO A POLICE OFFICER IN CALIFORNIA?