![]() Can I Sue the Police for a Malicious Criminal Prosecution? If you pleaded guilty or were convicted by way of a jury or bench trial, the answer is “No”. If you were acquitted or your criminal case did not otherwise result in a conviction, the answer is “Maybe”, depending on a myriad of factors.

Can I Sue the Police for a Malicious Criminal Prosecution? If you pleaded guilty or were convicted by way of a jury or bench trial, the answer is “No”. If you were acquitted or your criminal case did not otherwise result in a conviction, the answer is “Maybe”, depending on a myriad of factors.

As shown below, there is no claim under California state law at all for a malicious criminal prosecution, and the federal constitutional tort of malicious is difficult to successfully prevail on.

The first time that the United States Supreme Court recognized the naked constitutional tort of malicious prosecution was on April 4, 2022 in Thompson v. Clark, 596 U.S. ___ (2022) when it recognized that under Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, that the “favorable termination” requirement for a federal constitutional malicious prosecution claim was merely that the underlying criminal prosecution was terminated without you being convicted, clearly stated that the constitutional claim for a malicious prosecution is alive and well.

As noted below, the last malicious prosecution claim that the Supreme Court dealt with prior to Thompson v. Clark skirted the issue of whether a malicious prosecution claims arose under the 4th Amendment to the Constitution. Thompson v. Clark held that malicious criminal prosecutions arose from the 4th Amendment’s proscription against unreasonable searches and seizures. However, Thompson v. Clark did not dispense with the greatest obstacle to successfully prosecuting a federal malicious prosecution claim; the presumption that the prosecutor acted with his/her independent judgment in deciding to prosecute the malicious prosecution plaintiff; something quite difficult to prove.

Nonetheless, as shown below, difficult as it may be, one can in some cases successfully recover damages for the federal constitutional tort of malicious prosecution.

The Police Use Malicious Criminal Prosecutions to Protect Themselves from Liability for Their Outrages Perpetrated Against the Public.

Malicious criminal prosecutions of the victims of police abuse are rampant; especially for patently ambiguous and constantly abused “resistance offenses” like “resisting / obstructing / delaying a peace officer in performance of duties“ or “preventing / deterring public officer from performing duties“. Can I Sue For A Malicious Criminal Prosecution

When the police falsely arrest you or beat you or do other terrible things to you, with few exceptions, the police almost always at least to attempt to procure your bogus criminal prosecution, when you were the victim and they are the criminal. This is no joke. This is normal. This is the world in which you live. They do this to shift the blame from them to you and to preclude you from being able to successfully sue them from vindicating your constitutional rights and your honor and dignity. Under California state law, a police officer is absolutely immune for attempting to frame you for a crime that you didn’t commit, and even if you receive a finding of factual innocence from the judge who presided over your bogus criminal action. Moreover, neither the police officer nor the public entity who employed them while he/she attempted to frame you are civilly liable to those who they attempted to frame.

| Police Misconduct Specialties: | ||

|

|

|

This article shows what you, the victim of an attempted police frame-up, can do to obtain redress for your malicious criminal prosecution, and what obstacles lay in your path to vindication. The short answer is “No” under California state law, and “Probably” under the present state of federal constitutional law. Here is why.

How Police Officers So Easily Procure Your Malicious Criminal Prosecution.

When you are beaten by the police, they have taken that step from which there is no return. If they don’t arrest you, then they are tacitly admitting that your beating was unlawful. Therefore, if the police beat you, you are the one going to jail; not them (of course, unless there’s a video).

Moreover, that officer who falsely arrested you now has to justify the arrest by submitting a crime report falsely reporting that your committed a crime against them. The Detectives pick up the reports, look them over and submit them to the District Attorney’s Office for criminal prosecution. The reports are usually a collection of fiction and material lies and omissions; the goal being to falsely and maliciously procure your bogus criminal prosecution. The street cops may not know fancy legal terms like “collateral estoppel” or know the case name of Heck v. Humphrey, but they know that if your convicted of committing some sort of crime against them, then you generally cannot sue them. They know that and that’s enough.

Moreover, personal, peer and institutional / administrative pressures, demand that the peace officer neither admit his/her mistake of law, nor apologize for same. Police agencies never admit that they’re wrong, and never apologize. Most of the times these frame-ups by police officials are simply the officer shifting the blame for his use of force upon you and his false arrest of you (i.e. “The suspect strike my fist with his chin”).

Nothing personal, but sorry, someone is “in the wrong” and a conviction shows that it’s you. That’s the malicious prosecution game. Deputy District Attorney’s who are typically assigned to reviewing cases submitted to the DA’s Office for criminal case filings almost always make that decision to file based on the police reports only. They don’t have time to review audio or video recordings of the incident; often having to review between 20 and 50 cases per day for decisions on criminal filings on those cases. These Deputy District Attorney’s who are assigned to case filings don’t have time to interview witnesses, or listen to audio recordings, or to even watch a video of the very incident that they are making that decision on. In largely populated judicial districts, these “filing deputies” usually have about twenty minutes to read the police reports submitted to the DA’s Office, and to make a decision to file whether or not to file a criminal action, and, for what crimes. That’s it.

The DA’s who file these criminal cases don’t call you on the phone and ask for your side of the story. They don’t care. They indulge the police with an undeserved strong presumption of honesty, and based on the (sorry folks) lies in the police report, they file and persecute the crime victims. It’s really pretty simple. What the heck; if the DA finds out that the constable is lying, nothing will happen to him anyway. The DA has already chosen sides, and it’s not your side.

Even if You Can Prove Beyond Any Doubt That the Police Tried to Frame You, You Still Have No Remedy Under California State Law.

The California Law Review Commission was created by statute in 1953, to assist the Legislature and the Governor by examining California law and recommending needed reforms. In 1963 the California Law Review Commission studied the then existing common law immunities for public employees, including judges, prosecutors and police officers (i.e. absolute Judicial Immunity, Stump v. Sparkman, 435 U.S. 349 (1978)), and absolute immunity for criminal prosecutors (Imbler v. Patchman, 424 U.S. 409 (1975).) “Common law immunities”, are immunities enjoyed by usually governmental officials from claims or even lawsuits, that were “created” by judicial fiat; by the learned Judges of our state courts and of the federal bench. The word “common law” literally means judge made law, and judges really like creating legal doctrines to insulate themselves, public prosecutors and peace officers from liability for even blatant and admitted constitutional violations by such government officials.

The California Law Review Commission was created by statute in 1953, to assist the Legislature and the Governor by examining California law and recommending needed reforms. In 1963 the California Law Review Commission studied the then existing common law immunities for public employees, including judges, prosecutors and police officers (i.e. absolute Judicial Immunity, Stump v. Sparkman, 435 U.S. 349 (1978)), and absolute immunity for criminal prosecutors (Imbler v. Patchman, 424 U.S. 409 (1975).) “Common law immunities”, are immunities enjoyed by usually governmental officials from claims or even lawsuits, that were “created” by judicial fiat; by the learned Judges of our state courts and of the federal bench. The word “common law” literally means judge made law, and judges really like creating legal doctrines to insulate themselves, public prosecutors and peace officers from liability for even blatant and admitted constitutional violations by such government officials.

Although one 2011 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals case held that public prosecutors may even be sued for malicious criminal prosecutions (“A criminal defendant may maintain a malicious prosecution claim not only against prosecutors but also against others —including police officers and investigators —who wrongfully caused his prosecution”) Smith v. Almada, 640 F.3d 931 (9th Cir. 2011), his was a clear misstatement of well-established law regarding prosecutorial immunity; that of a public prosecutor. See, Imbler v. Patchman, 424 U.S. 409 (1975) (absolute prosecutorial immunity for filing and prosecuting any criminal action.) The Ninth Circuit cannot simply ignore Imbler because it’s a U.S. Supreme Court case, and it hasn’t been reversed.

In reviewing the then existing common law immunity of a public employee for a malicious criminal prosecution, the California Law Review Commission recommended that although individual liability of for public employees be kept, that the public employer be liable for the malicious criminal prosecution by its employee:

“7. The immunity from liability for malicious prosecution that public employees now enjoy should be continued so that public officials will not be subject to harassment by “crank” suits. However, where public employees have acted maliciously in using their official powers, the injured person should not be totally without remedy. The employing public entity should, therefore, be liable for the damages caused by such abuse of public authority; and, in those cases where the responsible public employee acted with actual malice, the public entity should have the right to indemnity from the employee.” California Law Review Commission, Recommendation relating to Sovereign Immunity; Number 1-Tort Liability of Public Entities and Public Employees January 1963; p.817.

Contrary to that recommendation of the California Law Review Commission, that a person who is the victim of an attempted frame-up should have some legal remedy, the California legislature enacted Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6, that provides for absolute malicious prosecution immunity for any public employee, acting in the course and scope of their employment. It is wrong and it is simply evil. It may be the great injustice in our criminal justice system in California.’

Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6 Provides:

“821.6. A public employee is not liable for injury caused by his instituting or prosecuting any judicial or administrative proceeding within the scope of his employment, even if he acts maliciously and without probable cause.”

This is simply malicious prosecution immunity under California state law for any public employee, including peace officers, acting in the course and scope of their employment. This section represents an exercise of “sovereign immunity“; “the King can do no wrong.” The California Courts have bent-over backwards (or “forwards” for sticking it to you, the body politic) to protect police officers from being liable for damages caused by their attempted framing of persons; including damages for innocents having to sit in jail on trumped-up charges that were almost always brought to justify the unjustified use of force, or brought to justify an officer’s premature arrest of a person.

Accordingly, in the State of California, if a police officer arrests you and procures your criminal prosecution based on known material lies contained in the officer’s police report, and you remain in jail for years awaiting trial because you can’t make bail, even if you are totally innocent and even if you prove that at trial so well that the trial Judge makes a “Finding Of Factual Innocence” (stating that you were not just found not guilty, but that in the Judge’s view you are totally innocent), the police officer cannot be sued for one penny under California law. He/she has absolute immunity. That has been the law of California since it’s inception; first by “common law” doctrine, and in 1963, by statute.

Frankly Ladies and Gentlemen, this is outrageous, and downright un-American. It’s morally wrong (i.e. “Thou shalt not bear false witness”), it’s ethically wrong (what could be worse than framing your victim), and it simply should not be tolerated. However, if this author had a nickel for every falsehood testified to by a peace officer in LA County, he would be richer than Bill Gates. However, notwithstanding California’s absolute immunity for a malicious criminal prosecution by a police officer, a federal remedy probably exists; probably.

From 1994 To 2023 California Law Expanded Malicious Prosecution Immunity to Any Police Actions Associated With a Criminal Investigation.

As shown above, when the California Legislature rejected the recommendation of the California Law Review Commission, and immunized public employees (acting in the course and scope of their employment) from malicious prosecutions by them; nothing more. Earlier California cases limited the scope of section 821.6 to its obvious meaning; that Section 821.6 only provides immunity for malicious prosecutions; not for other California torts. See, Sullivan v. County of Los Angeles, 12 Cal.3d 710 (1974) (Section 821.6 doesn’t provides immunity for anything other than for a malicious prosecution.)

Up until 2022, finding a new way to stick-it to the public to protect incompetent or corrupt police officers, the California Courts expanded, ad nauseam, malicious prosecution immunity to other actions that had never been deemed associated with actual criminal prosecutions. This “theory” of what police conduct was immunized from civil liability (i.e. getting sued), is nonsensical, intellectually dishonest, and did nothing other than create a license for California peace officers to lie, cheat and trample your rights. For example, under this expansion of Section 821.6, the police are immune for perjuring themselves on a search warrant application, to a Judge to get a search warrant for your home (Kilroy v. State of California, 119 Cal.App.4th 140 (2004).)

In California Courts (but not in federal courts) California peace officers were also immunized from being held accountable for using force or violence to prevent, dissuade or retaliate against you for exercising your Constitutional rights (save a claim based on a false arrest theory; Gillan v. City of San Marino, 147 Cal.App.4th 1033 (2007), and for any actions by the police associated with their investigatory functions; even for defamation / libel. See, Ingram v. Flippo, 74 Cal.App.4th 1280 (1999.)

The rationale for this unwarranted and simply evil expansion of Section 821.6, is that since you can’t have a criminal prosecution without an investigation (except when the police are beating you up or falsely arresting you, so there’s no need for any “investigation”), and since you can’t have an investigation without a detention and/or an arrest and/or a search, let’s just immunize police officers for everything associated with any criminal investigation; no matter how malicious or in bad-faith it’s being carried-out; whether or not it results in any prosecution, other than false arrest / false imprisonment and/or a battery. See, Amylou R. v. County of Riverside, 28 Cal.App.4th 140 (1994) (Government Code Section 821.6 immunity for all police investigations, save false arrest and battery), and Kilroy v. State of California, 119 Cal.App.4th 140 (2004) (Section 821.6 immunity even immunizes a police officer obtaining the issuance of a search warrant, when obtained by deliberate falsehoods made to issuing Judge.)

Police officers may not be all that familiar with words like “res judicata“ or “collateral estoppel“, or may not of even heard of Heck v. Humphrey, but they know enough; that if they get you convicted, you definitely cannot sue the officer for either false arrest or malicious prosecution, and, most likely, you can no longer sue (either as a practical or technical matter) for the use of unreasonable force upon you. Therefore, in order to protect him/her self from any criminal liability (i.e. 18 U.S.C. §§ 241 [conspiracy to deprive of federal Constitutional rights] & 242 [violation of federal Constitutional rights under color of law]; Cal. Penal Code § 146 [unlawful detention or arrest by peace officer] 149 [beating / torturing prisoners], 236 [false imprisonment], 192 [manslaughter], 187 [murder] and 245 [assault with deadly weapon / by means resulting in great bodily injury]), civil liability (i.e. federal civil remedy for violation of federal and statutory rights under color of state law [42 U.S.C. § 1983]), and California state law claims for battery, assault, false arrest / false imprisonment, wrongful death, violation of Cal. Civil Code § 52.1(retaliation for exercise of, or in attempt to, dissuade prevent another from exercising Constitutional rights), or administrative discipline (i.e. reprimand, suspension, rank reduction, and termination.)

Notwithstanding the absurd and cruel creation of immunity for peace officers that went well beyond the literal wording and clear meaning of Section 821.6 by the California Courts of Appeal, in 2016, Tort claims are typically matters of state law, raising no federal question. However, the conduct complained of may also violate the federal Constitution. In such a case, relief may be available in a federal court under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, which authorizes “constitutional torts”, by creating a private right of action in federal court (Congress even allowing federal claims in a state court), against any person who, “under color of [state law],” causes injuries by violating an individual’s federal Constitutional or statutory rights. Section 1983, however, “is not itself a source of substantive rights, but a method for vindicating federal rights elsewhere conferred by those parts of the United States Constitution and federal statutes that it describes.” Baker v. McCollan, 443 U.S. 137, 144 n.3 (1979.) Therefore, in order to bring a malicious prosecution claim under Section 1983, a malicious criminal prosecution must be deemed a deprivation of a right “secured by the Constitution.” 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

However, in 2023 in Leon v. County of Riverside, Case No. S269672, June 22, 2023, the California Supreme Court finally overruled Amylou R. v. County of Riverside, 28 Cal.App.4th 140 (1994) and held that California Government Code Section 821.6 immunity only provides immunity to police officers for malicious criminal prosecutions, but not for any other actions by them. This decision overruled Amylou R.’s immunity to the police for 29 years; from 1994 to 2023.

For Seven Years Prior To Leon v. County of Riverside, The Ninth Circuit Court Held That Government Code Section 821.6 Only Provided Immunity for Malicious Prosecutions.

On July 5, 2016, the Ninth Circuit handed down the seminal case of Garmon v. Cty. of Los Angeles, 828 F.3d 837, 847 (9th Cir. 2016), which rejected the California Court of Appeal’s ad nauseam expansion of Section 821.6 immunity and refused to immunize police officers pursuant to that section. In that Opinion, the Ninth Circuit held that they are only bound to follow state law on state law issues when either the highest court in a state (i.e. the California Supreme Court on California law) has decided that issue, or, when the state Courts of Appeals have decided an issue and the federal court finds that the state Supreme Court would have held otherwise. In reaching that holding that Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that the California Supreme Court already interpreted [California Government Code] section 821.6 as ‘confining its reach to malicious prosecution actions.’ “Sullivan v. County of Los Angeles, 12 Cal.3d 710, 117 Cal.Rptr. 241, 527 P.2d 865, 871 (1974), and that in their opinion, the California Supreme Court would adhere to Sullivan, notwithstanding many Opinions of the California Courts of Appeal holding otherwise.

Federal Malicious Prosecution Law From 1994 To 2017.

On the basis of dicta expressed by the plurality opinion in Albright v. Oliver, 510 U.S. 266 (1994), from 1994 to March 20, 2017 there was a wide political and practical acceptance of a federal constitutional right to be free of a malicious criminal prosecution; a frame-up by state actors. There are a myriad of Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals cases that allow the plaintiff in your typical police “beat-em-up” and “hook-em up” case, that allow the plaintiff who was deemed to have been falsely arrested and the victim of unreasonable force by police officers, to obtain monetary redress (i.e. money), as discussed below.

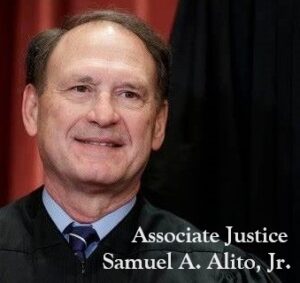

This political and practical consensus in the law was that a malicious criminal prosecution violates the Fourth Amendment’s proscription against “unreasonable searches and seizures”, but was not considered substantive due process violation under the Fourteenth Amendment. See, Albright v. Oliver, 510 U.S. 266 (1994) (malicious prosecution not substantive due process violation). This makes no sense, as police conduct that “shocks the conscience” that is not specified by a particular constitutional provision falls under the category of constitutional torts that constitute substantive due process violations. Even the most ant-civil rights and pro-police justice of the Supreme Court recognized that if a malicious criminal prosecution is a constitutional violation at all, it should be considered a substantive due process violation under the 14th Amendment:

I agree with the Court’s holding up to a point: The protection provided by the Fourth Amendment continues to apply after “the start of legal process,” ante, at 1, if legal process is understood to mean the issuance of an arrest warrant or what is called a “first appearance” under Illinois law and an “initial appearance” under federal law. Ill. Comp. Stat., ch. 725, §§5/109–1(a), (e) (West Supp. 2015); Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 5. But if the Court means more—specifically, that new Fourth Amendment claims continue to accrue as long as pretrial detention lasts—the Court stretches the concept of a seizure much too far.

What is perhaps most remarkable about the Court’s approach is that it entirely ignores the question that we agreed to decide, i.e., whether a claim of malicious prosecution may be brought under the Fourth Amendment. I would decide that question and hold that the Fourth Amendment cannot house any such claim. If a malicious prosecution claim may be brought under the Constitution, it must find some other home, presumably the Due Process Clause. See, Manuel v. Joliet, 580 U.S. ___ (2017), Alito, J., Dissenting:

Most United States District Courts and the United States Courts of Appeals (the federal intermediate level appellate courts) permitted a Section 1983 remedy for a malicious criminal prosecution by a peace officer. The First, Second, and Eleventh Circuits composed the “Tort Circuits,” wherein plaintiffs pleading malicious prosecution claims under Section 1983, were required to satisfy the common law elements of a malicious prosecution claim, in addition to proving a constitutional violation. The “Constitutional Circuits”—the Fourth, Fifth, Seventh, and Tenth — concentrated on whether a constitutional violation exists.

Most of the Circuits of the United States Courts of Appeals (save the seventh circuit that is headquartered in Chicago), allowed for an aggrieved person the right to sue for being subjected to a malicious criminal prosecution, federal (via 42 U.S.C. § 1983.) They did so based on various theories, since the right to be free from a malicious criminal prosecution is not described in the federal Constitution itself, but is nonetheless the type of pure evil and outrageous government action, that calls out for a declaration from the Supreme Court that such conduct constitutes a constitutional violation. It is so vile that it compels appellate judges to find some Constitutional foundation for that right, in order to allow a person who the government attempted to frame, some sort of remedy.

Although sister circuits categorized the Third Circuit as a “Tort Circuit”, the Third Circuit more recently acknowledged that “[o]ur law on this issue is unclear”; however, it continues to encourage plaintiffs to address each common law element. Similarly, the Sixth Circuit has avoided defining the required elements of a claim, although it appears to recognize a Fourth Amendment right against malicious prosecution and continued detention without probable cause. The Ninth Circuit lies on both sides of the divide; seemingly turning on whether they want the malicious prosecution plaintiff to prevail.

Until March 21, 2017, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that a person who the government attempted to frame may sue under Section 1983 for their malicious criminal state court prosecution, as a “naked constitutional tort”; as an unreasonable seizure under Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Galbraith v. County of Santa Clara, 307 F.3d 1119 (9th Cir. 2002.) This was the position of most of the other federal Circuit Courts of Appeals. The Ninth Circuit also continued its pre-Galbraith malicious prosecution jurisprudence and held that in in addition to constituting a Fourth Amendment violation, that one could sue for a malicious criminal prosecution if the prosecution was brought to deprive the innocent of some other constitutional right, such as attempting to frame an innocent in retaliation for protected exercise of First Amendment free speech. Awabdy v. City of Adelanto, 368 F.3d 1062, 1069–72 (9th Cir. 2004.)

In other words, some right other than the right to be free of a malicious criminal prosecution. This basis for the creation of the “Constitutional Tort” of “malicious criminal prosecution” by the Ninth Circuit; that you were maliciously prosecuted (i.e. attempted frame-up) to deprive you of some other Constitutional right, makes no sense. If the police attempted to frame you because you criticized them, that’s a straight-up First Amendment Free Speech / Right To Petition For Redress Of Grievances violation. You don’t need to prove the “constitutional tort” of malicious prosecution, as your damages are the same.

Notwithstanding that obvious exercise in logic, the Ninth Circuit nonetheless felt compelled to make that illogical construct in the 1980′s in Usher v. City of Los Angeles, 828 F.2d 556 (9th Cir. 1987). In that case a black man of African descent claimed that two LAPD officers beat-him-up and falsely arrested him while calling him a “nigger” and a “koon”, and latter attempted to frame him by submitting false police reports to the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office and lying at his trial; testimony that the jury didn’t believe. The Ninth Circuit allowed him to sue for his malicious prosecution, because it was brought to deprive him of “some other constitutional right”; in this case, the right to equal protection of the laws (i.e. actions committed because of Usher’s race.) That is, that the “malicious prosecution” was merely the tool that the officers used to deny Usher “equal protection of the laws.

On it face, however, Usher’s analysis is faulty. Under the Usher Line of case, all that the aggrieved plaintiff needs to show to claim to recover damages for their bogus malicious prosecution, is that the officers procured their bogus criminal prosecution to violate some other constitutional right. In Usher, his malicious prosecution was procured because of his race.True, in “complex causation cases” such as when a police officer procures someone else to do his dirt work (i.e. the Deputy District Attorney either suckered by the constable or who is desirous of using the criminal process to simply protect him), the plaintiff has to prove the absence of probable cause, even if the plaintiff can clearly show first amendment free speech / right to petition retaliation was the reason why the prosecution was brought. See, Hartman v. Moore, 547 U.S. 250 (2006) (for false arrest cases where the motive was first amendment retaliation, the plaintiff need not either plead or prove a lack of probable cause). See, Skoog v. County of Clackamas, 469 F.3d 1221 (2006) (plaintiff may pursue first amendment claim for his arrest as retaliation for protected speech claim, notwithstanding the existence of probable cause for the arrest.

Accordingly, the constitutional violation was a violation of Usher’s right to equal protection of the laws under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; exactly the equal protection that the 14th Amendment was designed to protect. Similarly, if the police had procured Usher’s bogus criminal prosecution because he verbally protested or verbally challenged their actions, then Usher could also recover damages for his malicious criminal prosecution as a violation of his right to Freedom of Speech / Right to Petition the Government for Redress of Grievances under the First Amendment.

Notwithstanding that pre-Galbraith and pre-Albright language, you can and could, as a real life practical matter, usually get a United States District Judge to allow you to sue for a malicious criminal prosecution as a “naked constitutional tort”, and they usually are not going to insist that your malicious criminal prosecution was brought to deprive you of some other right. However, to this day, the confusion has recently been cleared up in part, and made cloudy in part by the Supreme Court’s decision of March 21, 2017 in Manuel v. City of Joliet., No. 14–9496.

Federal Malicious Prosecution Law as Of March 21, 2017; Manuel v. City of Joliet,

As show in more detail below, the March 21, 2017 United States Supreme Court decision in Manuel v. City of Joliet, No. 14–9496 (March 21, 2017), essentially held that a police officer could be held liable for damages for the continued incarceration of one that he arrested, after the District Attorney’s Office filed formal criminal charges against Manuel:

“As reflected in those cases, pretrial detention can violate the Fourth Amendment not only when it precedes, but also when it follows, the start of legal process.

The Fourth Amendment prohibits government officials from detaining a person absent probable cause. And where legal process has gone forward but has done nothing to satisfy the probable-cause requirement, it cannot extinguish a detainee’s Fourth Amendment claim.

That was the case here: Because the judge’s determination of probable cause was based solely on fabricated evidence, it did not expunge Manuel’s Fourth Amendment claim. For that reason, Manuel stated a Fourth Amendment claim when he sought relief not merely for his arrest, but also for his pre-trial detention.” (Kagan, J., slip opinion at p.2).

Because of the Supreme Court case law that resulted in the Manuel decision, a judicial scholar would opine whether the Supreme Court has either permitted a straight-up malicious criminal prosecution when there was no pre-trial confinement (i.e. posting bail to avoid arrest after warrant issued), and, if malicious prosecution actions still need to show the common law elements of the tort of malicious prosecution to succeed on a straight-up malicious prosecution claim. This will be the subject of future cases in both the state and federal courts for years to come. After all, it took the 23 years since Albright v. Oliver, 510 U.S. 266 (1994). to have an actual operative majority of Supreme Court justices to finally declare what Albright opined in dicta in footnotes in 1994; that a police officer can be held liable for an arrestee’s confinement in jail after the District Attorney’s Office files a criminal case against him, and he can’t or won’t make bail. Now, for the next 23 years the lawyers and the judges get to argue whether a straight-up malicious criminal prosecution is a naked constitutional tort, without any arrest of the falsely accused.

As Justice Alito stated in his Dissent in Manuel v. Joliet:

“I agree with the Court’s holding up to a point: The protection provided by the Fourth Amendment continues to apply after “the start of legal process,” ante, at 1, if legal process is understood to mean the issuance of an arrest warrant or what is called a “first appearance” under Illinois law and an “initial appearance” under federal law. Ill. Comp. Stat., ch. 725, §§5/109–1(a), (e) (West Supp. 2015); Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 5. But if the Court means more—specifically, that new Fourth Amendment claims continue to accrue as long as pretrial detention lasts—the Court stretches the concept of a seizure much too far.

What is perhaps most remarkable about the Court’s approach is that it entirely ignores the question that we agreed to decide, i.e., whether a claim of malicious prosecution may be brought under the Fourth Amendment. I would decide that question and hold that the Fourth Amendment cannot house any such claim. If a malicious prosecution claim may be brought under the Constitution, it must find some other home, presumably the Due Process Clause.” Alito, J., Dissenting

In 2022 the U.S. Supreme Court Finally Recognized the Constitutional Tort of Malicious Prosecution if the Arresting Officer Also Procured the Underlying Criminal Prosecution, Thompson v. Clark.

On April 4, 2022, the United States Supreme Court published its opinion of Thompson v. Clark, 596 U.S. ___ (2022).

Prior to Thompson v. Clark, in most of the federal Circuits, in order to successfully establish a claim for malicious prosecution, a malicious prosecution under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, the plaintiff must have proved that: (1) the underlying criminal case was “instituted without probable cause”; (2) the police officers acted maliciously in procuring the filing of the criminal case, and that (3) the prosecution was “terminated in a manner inconsistent with guilt”.

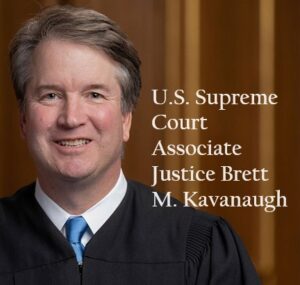

The third element, requiring favorable termination, was at the center of the dispute between the parties in Thompson. In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court held that “a Fourth Amendment claim under § 1983 for malicious prosecution does not require the plaintiff to show that the criminal prosecution ended with some affirmative indication of innocence.”

Writing for the majority, Justice Kavanaugh emphasized how this result is aligned with “the American tort-law consensus as of 1871” – when the tort of malicious prosecution was born – as well as with “the values and purposes” of the Fourth Amendment. Since 1871, most courts that considered the favorable termination requirement of the tort of malicious prosecution held that the claim was satisfied if the prosecution ended without a conviction.

Writing for the majority, Justice Kavanaugh emphasized how this result is aligned with “the American tort-law consensus as of 1871” – when the tort of malicious prosecution was born – as well as with “the values and purposes” of the Fourth Amendment. Since 1871, most courts that considered the favorable termination requirement of the tort of malicious prosecution held that the claim was satisfied if the prosecution ended without a conviction.

Justice Alito, with Justices Thomas and Gorsuch joining him, dissented. In their view, the majority’s decision created a “grim monster” by morphing together the elements of “a Fourth Amendment unreasonable seizure claim and a common law malicious-prosecution claim.”[28] Justice Alito’s primary focus is the fact that there is no overlap between the elements of the two claims.[29] To this point, he is correct in identifying the distinction between the two: the cause of action for malicious prosecution is based on the conduct of prosecuting the action, while the cause of action for a violation of rights under the Fourth Amendment is based on the arrest. Usually, the actors in each context are distinct – the former being prosecutors, while the latter being police officers.

Despite this, the dissent sidesteps an important factual distinction that perhaps sets this case apart from other malicious prosecution cases: those who instigated the arrest, the police officers, also instigated the alleged malicious prosecution. In such situations, a malicious prosecution case can be brought against police officers if they “instigate” the prosecution. Moreover, regardless of whether prosecuting attorneys or police officers instigate the prosecution, there remains a connection to a Fourth Amendment violation of constitutional rights because the arrest leading to the prosecution is rooted in the Fourth Amendment. The Court and its precedents recognize this nexus – “If the complaint is that a form of legal process resulted in pretrial detention unsupported by probable cause, then the right allegedly infringed lies in the Fourth Amendment.”

The outcome of this case will give claimants pursuing § 1983 claims for malicious prosecution a fighting chance. Justice Kavanaugh implies this in his majority opinion, noting how unreasonable it would be for an individual to rely on a prosecutor or court to explain why criminal charges against him or her were dismissed. To require that would simply be unrealistic and unfair, because it is unlikely that the prosecution would ever be forthcoming with such information.

While, in theory, removing the affirmative indication of innocence condition of the favorable termination requirement will ease the burden for claimants pursuing § 1983 claims for malicious prosecution, individuals pursuing such claims, in general, still have high hurdles to jump.

The Greatest Obstacle to Obtaining Damages for One’s Malicious Criminal Prosecution; the Presumption of Regularity of Governmental Actions; Actions With Either Real Evidence or Independent Witnesses.

A police officer will be deemed to have procured (to have legally “caused”) a malicious criminal prosecution if he submits materially false police reports that prosecutorial authorities rely on in deciding to file criminal charges against the Section 1983 plaintiff, or, if he pressures the prosecutor in filing the case, when he wouldn’t have otherwise done so, or when the prosecutor fails to use their independent judgment and become a rubber stamp for the police. See, Smiddy v. Varney, 803 F.2d 1469 (9th Cir. 1986) (malicious prosecution plaintiff must rebut presumption of independent prosecutorial judgment [that is, the presumption of the regularity of governmental proceedings under the federal rules of evidence] in deciding to prosecute, by showing that prosecutor either relied on materially false representations by police, or succumbed to pressure by the police (or others), such as filing the criminal action, to protect the police; not because the defendant was guilty.) See also, Borunda v. City of Richmond, 885 F.2d 1384, 1389 (9th Cir. 1988); Barlow v. Officer George Ground, 943 F.2d 1132 (9th Cir. 1991); Usher v. City of Los Angeles, 828 F.2d 556 (9th Cir. 1987), Karim-Panahi v. Los Angeles Police Department, 839 F.2d 621 (9th Cir. 1988.)

“A plaintiff who proves that police arrested him without probable cause is entitled to compensation for the economic and non-economic damages he incurs as a proximate result of these violations. Borunda v. City of Richmond, 885 F.2d 1384, 1389 (9th Cir. 1988). Reasonable attorney’s fees incurred by the plaintiff can constitute part of the foreseeable economic damages, unless the prosecutor’s decision to file charges is such an independent judgment that it must be considered the proximate cause of the subsequent criminal proceedings. Id., at 1389-90. However, under California state law, you cannot obtain damages for your false arrest, for your continued incarceration in jail, after than point in time when the District Attorney files criminal charges against you with the Court. See, Asgari v. City of Los Angeles, 15 Cal. 4th 744 (1997.) The rationale for that holding is that since Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6 provides immunity to any California public employee (acting in the course and scope of their employment) from civil liability for damages caused by their procuring your bogus and malicious criminal prosecution, that they are not civilly liable to you for any continued confinement of you in jail because of your criminal prosecution. Accordingly, under California state law, a police officer who falsely arrests you may be liable in damages to you for your arrest and incarceration; but only for that period of time prior to the DA’s Office filing a criminal case against you. If you’re required to post bail to be released from pre-trial custody, and you either can’t or won’t post bail, or, if you’re simply denied bail and have to remain in jail before your trial, the dirty rat cop that falsely procured your completely bogus criminal prosecution isn’t liable for either your confinement on false charges, or for having to defend those bogus charges.”

So, although California state law absolutely immunizes peace officers and any other public employee acting the course and scope of their employment for attempting to frame innocents, federal law no longer does; at least when there was an actual arrest of that person falsely accused.

THE GREAT OBSTACLE TO OBTAINING DAMAGES FOR ONE’S MALICIOUS CRIMINAL PROSECUTION; NEWMAN v. COUNTY OF ORANGE.

In Newman v. County of Orange, 457 F.3d 991 (9th Cir. 2006) the Ninth Circuit Ignored Circuit precedent, traditional tort law principles of causation and Supreme Court law on Summary Judgment Motions, in favor of a judicially created policy of protecting police frame-ups of innocents and encouraging police perjury and outrages.

Notwithstanding Smiddy v. Varney’s longstanding rule of causation and how the presumption of prosecutorial independent judgment may be rebutted, in Newman v. County of Orange, the Ninth Circuit ignored well established Circuit precedent, the Supreme Court, logic, reason, and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and of Evidence. Newman held that if the only evidence that a malicious prosecution plaintiff can produce is his own sworn testimony to show that the police provided false information to the prosecutor, that such sworn testimony is not sufficient to rebut the presumption of prosecutorial independent judgment in deciding to file the criminal action:

“Sloman did not and does not point to any evidence of . . . fabrication other than the fact that the officers’ reports were inconsistent with Sloman’s own account of the incidents leading to his *995995 arrest. Such conclusory allegations, standing alone, are insufficient to prevent summary judgment. Id. Because Sloman had no evidence of material omissions, or inconsistent police or eyewitness accounts, he could not demonstrate a genuine issue of material fact as to whether the prosecutor exercised independent judgment. Summary judgment for the defendant officers was therefore appropriate. Id.

“ . . . First, Newman’s argument places the focus on the wrong party. The question, under Smiddy, is not whether the prosecutor, in the face of conflicting accounts, would have filed charges based on the plaintiffs story, but whether she would have done so based on the officer’s. Prosecutors generally rely on police reports — not suspect’s stories — when deciding whether charges should be filed. We presume they rely on their independent judgment when deciding whether such reports warrant the filing of criminal charges, unless contrary evidence is presented. If charges are filed, Smiddy protects the officers unless such evidence shows that officers interfered with the prosecutor’s judgment in some way, by omitting relevant information, by including false information, or by pressuring the prosecutor to file charges. A suspect’s account of an incident, by itself, is unlikely to influence a prosecutor’s decision, and thus, it cannot, by itself, serve as evidence that officers interfered with the prosecutor’s decision. “

Indeed, Newman’s argument would effectively nullify the presumption entirely. We are hard-pressed to conceive of a malicious prosecution case in which the plaintiffs version of events would not conflict with the arresting officer’s account. In virtually every case, then, the presumption would be rebutted, and it would never limit the liability of the officer, contrary to its stated purpose.

With all due respect to the Ninth Circuit, this analysis is nonsense; a complete breakdown in logic and obvious common sense. It will do nothing other than shove the dagger of evil through the heart of truth, justice and the American way.

First, many prosecutors will meet with potential criminal defendants to seek their side of the story. Plaintiff counsels in this case have both taken criminal defendant to the District Attorney’s Office and had them dismiss cases (or not file them) based on a “suspect’s” account of the events.

Second, the Ninth Circuit’s statement, “Newman’s argument places the focus on the wrong party. The question, under Smiddy, is not whether the prosecutor, in the face of conflicting accounts, would have filed charges based on the plaintiffs story, but whether she would have done so based on the officer’s.”, shows a meltdown in logic. If the police officer’s version of the events contained material false statements of facts and/or material omissions of facts, and the District Attorney files a criminal charge on reliance of the police version being truthful, then the District didn’t act with his/her independent judgment in deciding to file that case, because the District Attorney’s judgment was based upon police lies. It’s that simple.

For example, say that a police officer, hypothetical Officer Smith, wanted to frame a man who was dating his sister; the hypothetical Mr. X, because he didn’t want her to marry him. Then assume that Officer Smith saw Mr. Jones walking down the street, and when Mr. X got close to Officer Smith’s patrol car, Officer Smith picked-up a rock and threw it through a window of his patrol car. Then assume that Officer Smith then arrested Mr. X for vandalizing his patrol car, and authored a police report in which Officer Smith claimed that he witnessed Mr. X throw a rock through the patrol car window. Then assume that Officer Smith’s police report was forwarded to the District Attorney’s Office, and in reliance on the contents of that bogus police report, the District Attorney files a criminal case against Mr. X for vandalizing the police car. Also assume that the case goes to trial and the jury believes Mr. X, and finds him not guilty. Mr. X then sues for his false arrest and his malicious prosecution.

In this situation, Officer Smith is the cause, or at least a “proximate cause” or “legal cause” of the prosecution of Mr. X. The District Attorney’s filing of the action doesn’t break the chain of causation because the District Attorney didn’t use his independent judgment, as the District Attorney wasn’t told the true facts. So, if the malicious prosecution plaintiff (Mr. X) proves that the material statements of facts contained in the police report are false, Mr. X then he has rebutted the presumption of regularity of governmental decision making. Nonetheless, under Newman, the wrongfully accused has no remedy, because the only material evidence that he/she has is his/her word. That is not right. That is not fair. That is frankly creepy.

In any malicious prosecution case, the Section 1983 malicious prosecution plaintiff necessarily was criminally prosecuted, and necessarily won his/her underlying criminal case. In any Section 1983 malicious prosecution case, the police were either able to convince the prosecuting authorities to file the criminal action based on the police version of the events, or somehow pressured the prosecuting authorities to file the action, or simply were able to procure the prosecution because the prosecutor was nothing more than a rubber-stamp for the police. Putting the second and third reasons for the criminal prosecution aside, rebutting of the presumption of the propriety of governmental decision making only involves the question of whether the prosecutor relied on material police lies. That’s it in toto.

The statement by the Ninth Circuit in Newman that “Newman’s argument places the focus on the wrong party. The question, under Smiddy, is not whether the prosecutor, in the face of conflicting accounts, would have filed charges based on the plaintiffs story, but whether she would have done so based on the officer’s.”, is just plain wrong. In any such case, the mere fact that the case was filed shows that the prosecutor “filed charges based on the officer’s story.” That’s the whole point; that the officer’s version of material events resulted in a bogus criminal prosecution, and, that the police version was a lie to frame the malicious prosecution plaintiff. That’s why the constable’s liable; not because he made a mistake, but because he lied to get the plaintiff prosecuted.

There is no logical or legitimate reason why a police officer who attempted to frame a malicious prosecution plaintiff can be deemed the cause of the plaintiff’s bogus criminal prosecution if the plaintiff has testimony from a witness other than himself/herself, but if there were no witnesses, even if the jury believes the plaintiff and not the officer, the officer cannot be held liable for the bogus criminal prosecution that he caused by lying to the prosecutor.

Unless the police pressured the prosecutor to file the subject criminal action, or the prosecutor was merely a “rubber stamp” for the police in prosecuting their victims, the only inquiry on causation, is whether the police lied to the prosecutor to procure the plaintiff’s bogus criminal prosecution. That’s it. Under the Ninth Circuit’s analysis in Newman, a police officer can lie to a prosecutor all that he wants to attempt to frame the plaintiff, and if the plaintiff doesn’t have a witness other than himself, no matter how much a jury believed that the constable lied to procure the plaintiff’s bogus prosecution, the constable escapes liability.

The fallacy of this analysis can be seen by the mere fact that the same malicious prosecution plaintiff who is barred by this rule from obtaining damages for his/her bogus criminal prosecution, can nonetheless still prove and obtain damages against the very same police officer for his false arrest, by showing that the police lied about the plaintiff’s same conduct. Take the example of the police beating-up an innocent, arresting him and then filing false police reports to get their victim prosecuted. In deciding whether the plaintiff was falsely arrested the finder of fact is called upon to determine whether or not the police version of the events is true or not. The issue of fact for a jury would be identical in either a malicious prosecution case, or a false arrest case for the same conduct by the police. So, the very same plaintiff who can prove that the constable lied to the DA (and to them) and attempted to frame the plaintiff, can obtain damages for his false arrest, but can’t obtain damages for his bogus criminal prosecution, even though those same police lies were the cause of the bogus criminal prosecution; even if the plaintiff can prove that the police version of the events is a lie, with their own sworn testimony only. This is an absurd and cruel rule, that cannot withstand either logical scrutiny or any semblance of decency or justice. Moreover, the Ninth Circuit’s logic for having such a rule shocks the conscience; to limit police liability, no matter how truly evil (i.e. that they need to limit police liability based on a fiction; the presumption of regularity of governmental actions.

Moreover, as shown below, this new rule of evidence contradicts the evidentiary standard for summary judgment motions contained in F.R.Civ.P. 56(e), and the standard established by Congress for rebutting evidentiary presumptions contained in F.R.E. 301[2].

A presumption is not evidence and may not be given weight as evidence. New York Life Ins. Co. v. Garner, 303 U.S. 161,171, (1938); Routen v. West, 142 F.3d 1434, 1439 (Fed. Cir. 1998). It merely shifts the burden to the other party of coming forward with evidence (the burden of production), and does not shift the burden of persuasion. Wards Cove Packing Co. v. Atonio, 490 U.S. 642, 659-660, (1989).

“Federal Rules of Evidence 301 follows the “bubble bursting theory”. If the presumption is rebuttable and the foundational fact is controverted, then – the bubble having been burst – the presumption is rebutted and drops from the case. Fed. R. Evid. 301; see Texas Dep’t of Cmty. Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248, 254-56, 67 L.Ed.2d 207, 101 S.Ct. 1089 (1981)” . . . In construing the “substantial” evidence standard for rebutting presumptions, the decisions tend to apply a clone of the directed verdict standard for determining when evidence is substantial enough to rebut the date stamp presumption. Silverton, 237 F.2d at 144. WEINSTEIN § 301.02[2] evidence presented to rebut a presumption must be sufficient to overcome a directed verdict.”

In re David C. Bryan, United States Bankruptcy Appellate Panel for the Ninth Circuit, 261 B.R. 240, 244 (2000).

“There is nothing in the Federal Rules of Evidence that somehow makes a plaintiff incompetent to testify as a witness in his own case, or not worthy of belief. It has long been held that the testimony of a single person is sufficient to defeat a motion for summary judgment. See, Dominguez-Curry v. Nevada Transp. Dept., 424 F.3d 1027, 1039 (9th Cir. 2005). Moreover, in a summary judgment motion, the court must accept the non-movant’s version of the facts as true, and refrain from making credibility determinations. Hopkins v. Andaya, 958 F.2d 881 (9th Cir. 1992.)”

“Credibility is the responsibility of jurors. “The judge’s function is not himself to weigh the evidence and determine the truth of the matter but to determine whether there is a genuine issue for trial . . . Credibility determinations, the weighing of evidence, and the drawing of inferences from the facts are jury functions. Anderson v. Liberty Lobby, Inc., 477 U.S. 242, 249-255, 106 S.Ct. 2505, 2511-2513, 91 L.Ed.2d 202 (1986).

Sorry folks; Newman is just a straight-up transparent nonsensical effort by Judges to thwart legitimate malicious prosecution plaintiffs from obtaining the redress that they are due.

Good luck,

Jerry L. Steering, Esq.

Published: 2/5/2019

Can I Sue the Police for a Malicious Criminal Prosecution?

Can I Sue the Police for a Malicious Criminal Prosecution?  I agree with the Court’s holding up to a point: The protection provided by the Fourth Amendment continues to apply after “the start of legal process,” ante, at 1, if legal process is understood to mean the issuance of an arrest warrant or what is called a “first appearance” under Illinois law and an “initial appearance” under federal law. Ill. Comp. Stat., ch. 725, §§5/109–1(a), (e) (West Supp. 2015); Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 5. But if the Court means more—specifically, that new Fourth Amendment claims continue to accrue as long as pretrial detention lasts—the Court stretches the concept of a seizure much too far.

I agree with the Court’s holding up to a point: The protection provided by the Fourth Amendment continues to apply after “the start of legal process,” ante, at 1, if legal process is understood to mean the issuance of an arrest warrant or what is called a “first appearance” under Illinois law and an “initial appearance” under federal law. Ill. Comp. Stat., ch. 725, §§5/109–1(a), (e) (West Supp. 2015); Fed. Rule Crim. Proc. 5. But if the Court means more—specifically, that new Fourth Amendment claims continue to accrue as long as pretrial detention lasts—the Court stretches the concept of a seizure much too far. “As reflected in those cases, pretrial detention can violate the Fourth Amendment not only when it precedes, but also when it follows, the start of legal process.

“As reflected in those cases, pretrial detention can violate the Fourth Amendment not only when it precedes, but also when it follows, the start of legal process.