When There is No Remedy, There is No Right

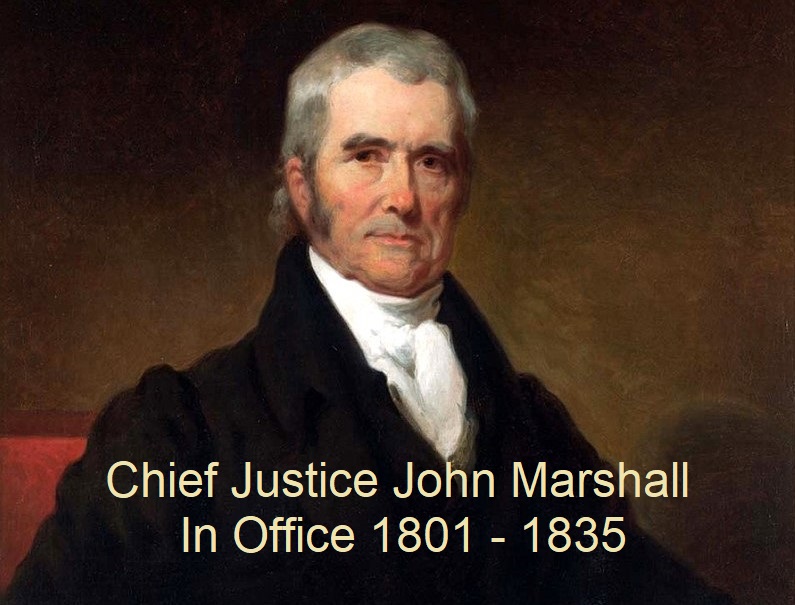

In probably the most famous and important United States Supreme Court case in history, Chief Justice John Marshall stated the obvious about constitutional rights in the young American Republic:

“It is a general and indisputable rule that where there is a legal right, there is also a legal remedy by suit or action at law whenever that right is invaded.” Chief Justice John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803).

The converse of that proposition is also true; where there is no remedy, there is no right.

That being said, the law is not what is says, but what it does. It doesn’t matter what they teach you in school, or what’s in a lawbook, or on the internet, or in the news. All that does matter is what happens to real people with real cases, with real judges and real juries.

In the end, if you cannot get a jury to vote for you and against the police, you have no rights, because you have no way to enforce them. For various reasons discussed below, more often than not, in the real world in police misconduct civil rights cases, they win and you lose. In the real world, you really do (almost) have no rights.

“Ubi Jus Ibi Remedium”, “For Every Right There is a Remedy”, is a Myth.

Americans generally believe that for every right there is a remedy; “Ubi Jus Ibi Remedium”. That belief system is misguided.

In the real world, between the Courts, the Congress, the Police Unions and the typical jury’s perception of today’s police officers, we have very few rights to protect us from police outrages, because in not most cases, no practical vehicle exists to enforce those rights.

In a very real sense, there is no such thing as the United States Constitution. The Constitution is nothing other than what the Ladies and Gentlemen of the Supreme Court say it is. It has never been anything else, nor will it ever be.

The United States Supreme Court has in recent times gone out of its way to convince the American people that the Supreme Court does not “make policy decisions”, but only interprets the Constitution and the federal laws. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Just read the “Opinions” of the Supreme Court (they’re free and online at Opinions of the Court – 2023 (supremecourt.gov)). Once you do so, it will become evident to you that if the Supreme Court was not making policy decisions, the cases wouldn’t be before them.

Lincoln was wrong. We are not a nation of laws, but a nation of men (and women). Men (and women) decided what the law is, whether to enforce it, how to enforce it, and who to enforce it against.

Due To Practical Considerations, Most Police Misconduct Civil Rights Cases Are Tried In Federal Court.

Most police misconduct civil rights cases are tried in federal court for several reasons.

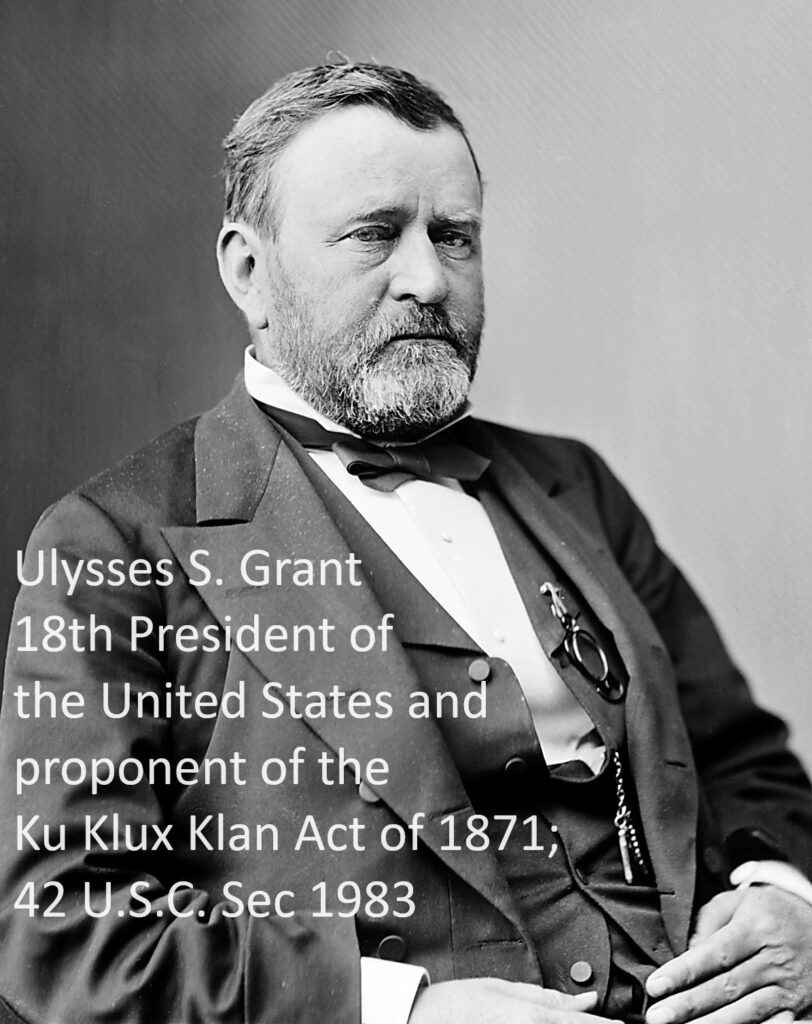

First, the statute for you to sue state and local police officers for violating your federal constitutional rights is 42 U.S.C. § 1983; a federal statute that gives the federal courts the jurisdiction to adjudicate your civil rights case. Even if you file your Section 1983 claims in a state court, the police defendants may remove that case to federal court, and they almost always do so pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1446.

As a practical matter, persons who have been subjected to a false arrest or the use of excessive force (or other constitutional violations) almost always need to sue the police under Section 1983, because a successful plaintiff in a Section 1983 civil rights case can obtain an award of Attorney’s Fees in addition to any judgment that they may obtain from a judge or jury.

The “American Rule” is that in the absence of a fee-shifting statute, each side to a civil lawsuit case pays their own attorney’s fees. Without the Attorney’s Fees provision of 42 U.S.C. § 1988 that provides for the award of Attorney’s Fees to a successful 42 U.S.C. § 1983 plaintiff, almost no one would be suing the police for the violation of their constitutional rights, unless the damages from such civil rights suit were upwards of a million dollars or more.

No lawyer is going to do hundreds of thousands dollars of work on a civil rights case, for 40% of $10,000.00, or even $100,000.00. Without the Attorney’s Fees award obtainable by a successful Section 1983 plaintiff, cases with less than high six-figure damages would just not be litigated. Moreover, malicious criminal cases for resistance offense cases (i.e. resisting peace officer, battery on peace officer), are very commonly procured by police officers to protect them from civil liability, as if one is convicted of such a resistance offense, one typically cannot sue the police; they are precluded from doing so under the doctrine of collateral estoppel, or via the policy doctrine created by the U.S. Supreme Court in Heck v. Humphrey, 512 U.S. 477 (1994) (cannot sue for false arrest of convicted, even if no warrant or probable cause for arrest).

Also, as in states like California, police officers are immune from lawsuits for their attempting framing of innocents (i.e. Cal. Gov’t Code § 821.6), one’s only remedy is the federal constitutional tort of malicious criminal prosecution, only actionable under 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

Many Police Misconduct Civil Rights Cases Cannot Succeed Because the Doctrine of Qualified Immunity is Too Often a Defense to a Federal Civil Rights Claim Brought Under 42 U.S.C. § 1983

Therefore, persons whose federal constitutional right have been violated, almost always need to sue under the federal civil rights protections of 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

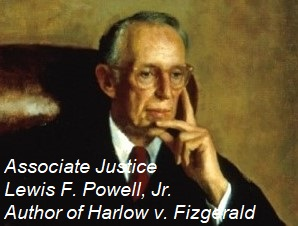

Qualified immunity is one of the most oppressive legal doctrines in our nation’s history. It is a doctrine created by the U.S. Supreme Court that shields government officials, such as police officers, from liability for their misconduct, even when they break the law.

Qualified immunity was first created by the U.S. Supreme Court in Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800 (1982). In that case the Supreme Court held that federal government officials are entitled to qualified immunity, because “the need to protect officials who are required to exercise discretion and the related public interest in encouraging the vigorous exercise of official authority”, requires that they carry out their duties, free from concern that they might be sued for doing so. This was a pure policy decision; nothing more.

In its modern-day form, qualified immunity prevents government agents from being held personally liable for constitutional violations unless the violation was of “clearly established law“, which usually requires specific precedent on point with the case before the court; both factually and legally.

Qualified Immunity is simply another doctrine made-up by the U.S. Supreme Court for policy reasons; to protect the police from liability for their outrages. It has drastically hampered the ability of victims of constitutional violations by public officials from obtaining redress in the courts. It allows the federal courts to contemporaneously declare that a civil rights plaintiff’s constitutional rights were violated, but he/she is nonetheless not entitled to be compensated for the violations of those rights because not every police officers would be on notice that their conduct constituted a constitutional violation, making a mockery of the Bill of Rights.

The application of qualified immunity to real cases of even the most egregious constitutional violations is day by day, case by case, turning the United States into a police state.

Unless you can show the court binding precedent that is so factually and legally similar to your case that no judge could possibly argue with a straight face that the police were not reasonably put on notice that such actions constituted constitutional violations, you lose; even when that same judge in that same case also declares that your constitutional rights were violated.

The issue of whether there was a constitutional violation must also be “beyond debate” See, Stanton v. Sims, 571 U.S. 3 (2013).

In the legal world almost nothing is “beyond debate“. Accordingly, in the real world with real judges, if any reasonable judge might have deemed the action permissible, the law is not “clearly established”; at least not for you. Moreover, the Supreme Court has now changed the qualified immunity analysis to essentially prevent any future cases of similar police outrages from being shown as constitutional violations; thus continuing to allow the police to continue to commit those same constitutional violations in perpetuity.

Qualified Immunity is one of the major reasons that in modern American society, you (almost) have no rights.

Many Police Misconduct Civil Rights Cases Cannot Succeed Because Almost all of the Juries Who Actually Get to Sit on Those Cases Are Mostly White, Conservative Cop-Loving Jurors

The Seventh Amendment, Rule 48 and the Jury Pool

Almost all Police Misconduct Cases sue the police for violation of their victims Federal

Almost all Police Misconduct Cases sue the police for violation of their victims Federal

Constitutional Rights, and, therefore, at least some of the claims brought by Police Misconduct Victims sue the Police under 42 U.S.C. § 1983; the 1871 statute enacted by Congress to give “black widows” (not the spider type) in the Post-Civil War Southern States a federal court venue to vindicate the violation of their federal constitutional rights.

Victims of police abuse also often sue the police under various state law statutes and common law torts, such as false arrest / false imprisonment, battery, assault, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and whatever state law remedies exists in their state for police abuse.

Although the United States Congress has given state courts of general jurisdiction the authority to sue the police under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, even if a police misconduct victim sues the police in their state’s court of general jurisdiction, like a state Superior Court, the police have a right to remove that case to the local federal district court under 28 U.S. Code § 1441 so long as the lawsuit contains a claim under a federal statute, such as 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Accordingly, as most police misconduct civil rights cases bring claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, most such cases end up being tried in a United States District Court; either because the civil rights plaintiff filed the case in federal court, or because the police removed the case from state court to federal court.

Under the Seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution, in a federal court civil case, when the amount sued for exceeds $20.00, all parties to that civil case are entitled to a trial by jury. Therefore, most police misconduct civil rights cases are decided by juries in United States District Courts. If by some chance the District Court Judge does not grant some Dispositive Pre-Trial Motion that disposes of your case before you get to trial (i.e. Motion to Dismiss for Failure to State a Claim, or Motion for Summary Judgment), the next obstacle that you have to overcome to win your federal constitutional rights are those jurors who decide who wins and who loses.

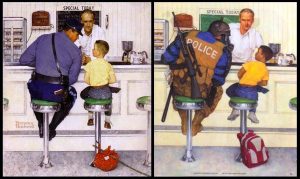

Other than a Police Misconduct civil rights lawsuit seeking Injunctive Relief (i.e. Order to the Sheriff to house inmates differently, Order to Police Agency to stop engaging in certain conduct), it is extremely rare that a Police Misconduct Civil Rights case is decided by a District Judge, and not a jury. Juries almost always decide Police Misconduct Civil Rights cases when the case makes it to trial. That being the case, the issue then becomes, what type of people actually get to sit on juries in police misconduct civil rights cases in federal court. The answer is pretty simple; fairly conservative, cop-loving and mostly white jurors, none or almost none of whom ever had or personally seen an instance of police misconduct.

None (or almost none) who have ever been or have had a loved one falsely arrested gets to sit in judgment in these type of case. None (or almost none) of whom has ever been or have had a loved one subjected to excessive force. None (or almost none) who have been or have had a loved one falsely accused of a crime by a police officer. None (or almost none) who, therefore, understand the real world of policing in America.

Here is why.

Why the Jury Selection Process Almost Always Results in Mostly White Cop-Loving Jurors Sitting in Judgment in Police Misconduct Cases

In the real world, almost none of those jurors who get to actually sit on police misconduct civil rights federal jury trial understand the reality of how many police officers really do bad things to people who don’t deserve it.

In the real world, almost none of those jurors who get to actually sit on police misconduct civil rights federal jury trial understand the reality of how many police officers really do bad things to people who don’t deserve it.

In federal court civil trials (cases seeking monetary damages), only six jurors are required for a verdict (Fed. Rule Civil Proc. 48), unlike federal criminal trials and most state criminal trials, where twelve jurors are required for a verdict.

Although Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 48 allows up to a maximum of 12 jurors in civil cases, United States District Judges usually have 8 jurors sit in Police Misconduct Civil Rights cases rather than the minimum 6 jurors, in the event that one or two of them get ill, or other problems arise with a juror. Accordingly, if one or two of those 8 jurors becomes ill, misbehaves or otherwise cannot continue to serve as jurors on the cases, there will usually be at least the mandatory 6 jurors left to render a verdict on the case.

Moreover, under Rule 48, there are no “Alternate Jurors” like in state court cases and in federal criminal cases. All of the jurors decide the case, and their Verdict must be unanimous under Rule 48.

During the jury selection process of those 8 jurors for police misconduct civil rights cases, the District Judge usually had the jury commissioner call-up a panel of 40 to 45 prospective jurors, who usually have been “pre-qualified” to sit by a United States Magistrate Judge. The “pre-qualification” process usually involves making sure that the panel of 40 to 45 prospective jurors do not have time conflicts or claims of economic hardship; claims that the prospective juror would suffer an “economic hardship” if they had to take the week or so off of work to sit as a juror on the case.

When such jurors do claim such an “economic hardship”, the Magistrate Judge might excuse them from jury duty, or send them up with the panel of 40 to 45 prospective jurors, for the United States District Judge to decide to excuse them from jury duty based upon their claim of time conflicts (i.e. medical appointments, pre-paid for vacations, students needing to take exams, etc.) or “economic hardship” (i.e. sole provider for family and could not pay their rent if they had to take off of work).

Thereafter, the District Judge and the lawyers will examine the 40 to 45 prospective jurors in a process called “voir dire“; French for “to speak the truth”.

During the voir dire questioning of witnesses, usually the District Judge, and sometimes the lawyers, will ask the prospective jurors if they or a close friend or loved-one have ever had a bad experience with the police, or have personally witnessed what they perceived a police misconduct. Typically, if the plaintiff is lucky, approximately 10 percent or less of those 40 to 45 jurors will raise their hands in response to that question; 3 or 4 jurors out of the panel of 40 to 45 prospective jurors.

The District Court will then ask those 3 to 4 jurors who (or close-friend or loved one) had a bad experience with the police, if that bad experience with the police would bias them against the police. That they would feel compelled to vote against the police defendants, or, without any evidence being heard yet, that the plaintiff is already starting ahead of the police in terms of which way that would decide the case. Usually, at least 2 of the 3 or 4 jurors who raised their hands to that question will say “Yes”; that they are biased against the police, or that the bad experience with the police would cause them to favor the plaintiff over the police when they vote for a verdict in the case. When those jurors make those statements, the District Court will then almost always those jurors will be “excused for cause” by the Court.

When a juror is “excused for cause”, the Court dismisses that juror, and neither party had to use one of their peremptory jury challenges to exclude that person from sitting on the jury. Say that there were as many as 4 jurors who answered affirmatively to the question of whether they or a close friend or relative had a bad experience with the police. Typically then, after excusing jurors for cause, there are now 1 or 2 jurors left who answered affirmatively to the question of whether they or a close friend or relative had a bad experience with the police.

In federal civil cases, each side to the case is allowed 3 peremptory juror challenges (the exclusion of a potential juror without the need for any reason or explanation) under 28 U.S. Code § 1870. Accordingly, the police defendants’ lawyers most assuredly will use their peremptory juror challenges to exclude any prospective jurors from sitting as jurors on the case who answered affirmatively to the question of whether they or a close friend or relative had a bad experience with the police. This leaves the only jurors who ultimately get to sit as jurors in police misconduct civil rights cases are people who have only had good experiences with the police. That is why the police usually win police misconduct civil rights cases; because of these mostly white and conservative cop-loving jurors. Because notwithstanding the evidence presented to them, these mostly white and conservative cop-loving jurors are just not inclined to vote against the police.

Again, if you cannot get these mostly white and conservative cop-loving jurors to vote for you and against the police, in the real world you have no rights, because you have no way to enforce those rights.

The Police Know How the Game is Played

In the real world of policing, if an officer lies for the department, he/she is lauded, maybe even promoted (no joke). However, if the officer tells the truth, and that truth implicates a fellow officer, he/she is ostracized or worse (i.e. not backed-up in the field while in danger) by his/her fellow officers, and, in the end, usually fired based on trumped-up charges by fellow officers and superiors.

In the real world of policing, if an officer lies for the department, he/she is lauded, maybe even promoted (no joke). However, if the officer tells the truth, and that truth implicates a fellow officer, he/she is ostracized or worse (i.e. not backed-up in the field while in danger) by his/her fellow officers, and, in the end, usually fired based on trumped-up charges by fellow officers and superiors.

Moreover, police officers are professional witnesses. They know how to testify, and they know that lying for the department is not considered a vice, but a virtue in the police world. That is the real world.

The movie “L.A. Confidential” is a lot more realistic than the general public either knows or would care to know. L.A. Confidential is a movie showing LAPD corruption and cover-ups of LAPD murders and other crimes and constitutional violations, from the District Attorney, the Chief of Police, on down the line.

When L.A. Confidential was released in 1997, this author spoke with the lawyer (and former LAPD Captain) who ran the Police Litigation Section for the Los Angeles City Attorney’s Office in 1997 about L.A. Confidential. That Senior Assistant City Attorney admitted to this author, that the way that police misconduct was shown in L.A. Confidential was very realistic, and was exactly how the LAPD handled those situations in the 1950’s, and for some time thereafter.

Things haven’t changed all that much at the LAPD and in most modern police departments. For example, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department has a long history of Deputy Gangs at the various Sheriff’s Department stations throughout Los Angeles County. See, the Report of the Los Angeles County Civilian Oversight Commission, discussing the reality of these Deputy Gangs; some of which the Deputy must actually commit an on-duty murder for admission to the gang, such as the Compton Station gang “The Executioners”.

Although successive Los Angeles County Sheriff’s have promised to do something about these Deputy Gangs, and although the California Legislature has passed laws to outlaw them, nothing has changed at the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

In the 2021 trial of Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin, the Chief of Police of the Minneapolis Police Department took the witness stand and testified that Officer Derek Chauvin’s conduct was “out of policy” of the Department, and that any reasonably well-trained police officer would know that Officer Chauvin’s conduct was outrageous and constituted the use of excessive force upon George Floyd. That was probably the first time that certainly the Minneapolis Chief of Police, and also probably the first or one of the very few times that a Minneapolis police officer testified that a fellow officer’s use of force was excessive. That just does not happen in the real world.

In the 2021 trial of Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin, the Chief of Police of the Minneapolis Police Department took the witness stand and testified that Officer Derek Chauvin’s conduct was “out of policy” of the Department, and that any reasonably well-trained police officer would know that Officer Chauvin’s conduct was outrageous and constituted the use of excessive force upon George Floyd. That was probably the first time that certainly the Minneapolis Chief of Police, and also probably the first or one of the very few times that a Minneapolis police officer testified that a fellow officer’s use of force was excessive. That just does not happen in the real world.

Rather, the police agencies “circle the wagons”, come-up with some choreographed false version of the use of force incident and lie about what happened under oath, and then have some “Court Whore” Expert Witness for Sale Use of Force Police Procedures Expert justify the subject Use of Force. That is what happens in the real world. Ask any lawyer or judge who deals with these cases off the record, and they will confirm this.

Moreover, in the real world, there is no such thing as perjury. The only people who get prosecuted for perjury, are politicians, DMW applicants and welfare recipients; that’s it. Just ask you local Deputy District Attorney.

There are always two sides to a story in court, and one of the sides is lying under oath. Besides, who is going to prosecute the police for lying for the police? The District Attorney’s Office or the U.S. Attorney’s Office? Not a chance. No one gets prosecuted for perjury in police misconduct trials.

The George Floyd case was nothing more than the political human sacrifice of Officer Chauvin. The “riotous mob” had burned-down a Minneapolis Police Department Precinct Station, and there were massive nationwide protests, riots and looting over George Floyd’s suffocation by Derek Chauvin.

U.S. Representative Maxine Waters, an African American woman, held a press conference in Minneapolis before the jury in the Chauvin criminal case had been sequestered, calling for nationwide riots if the jury did not convict Officer Chauvin; something that the trial judge called abhorrent.

U.S. Representative Maxine Waters, an African American woman, held a press conference in Minneapolis before the jury in the Chauvin criminal case had been sequestered, calling for nationwide riots if the jury did not convict Officer Chauvin; something that the trial judge called abhorrent.

Ironically, Representative Waters’ press conference was reminiscent of the days in the old South, when the KKK would gather around the courthouse and intimidate jurors to convict a black criminal defendant.

Other Reasons Police Misconduct Civil Rights Cases Cannot Succeed, Plaintiff’s with Extensive Criminal Histories

Federal Rule of Evidence 609 allow the Impeachment of a Witness with evidence that they have been convicted of any felony, or any misdemeanor of dishonesty, such as shoplifting. Accordingly, because police misconduct civil rights plaintiff invariably will have to testify at the trial of their civil case against the police, if their criminal conviction history is sordid enough, the jury won’ care what the police did to that person. It doesn’t matter if you have rights on paper, if not jury is going to care about them.