Atwater v. Lago Vista, 532 U.S. 318 (2001)

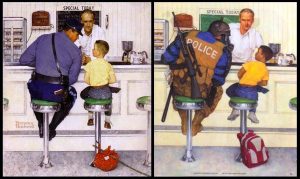

The police can arrest you for anything that the law prohibits; anything at all, no matter how trivial. (See, full U.S. Supreme Court Opinion at Atwater v. Lago Vista, 532 U.S. 318 (2001))

In Atwater v. Lago Vista, a City of Lago Vista police officer arrested Gail Atwater for driving her truck in Lago Vista, Texas, with her small children in the front seat. None of them were wearing a seatbelt. City of Atwater police officer Bart Turek verbally berated Mrs. Atwater, handcuffed her, placed her in his squad car, and drove her to the local police station, where she was made to remove her shoes, jewelry, and eyeglasses, and empty her pockets.

Officers took her “mug shot” and placed her, alone, in a jail cell for about an hour, after which she was taken before a magistrate and released on bond. She was charged with, among other things, violating the seatbelt law.

She pleaded no contest to the seatbelt misdemeanors and paid a $50 fine. She and her husband (collectively Atwater) filed suit under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, alleging, inter alia, that the actions of respondents (collectively City) had violated her Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable seizure.

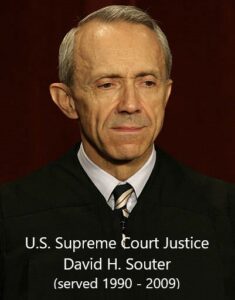

The United States Supreme Court held that because Officer Turek had probable cause to arrest Mrs. Atwater, and there was no evidence the arrest was conducted in an extraordinary manner, unusually harmful to Atwater’s privacy interests, the court (Justice Souter) held the arrest not unreasonable for Fourth Amendment purposes.

Accordingly, a police officer can arrest one for anything that the law prohibits; anything at all.

Although under various state laws, such as in California, a peace officer can only give you a Citation and cannot take you to jail for a minor traffic infraction if you have sufficient identification, because in California state law claim for false arrest does not provide for an award of attorney’s fees, and because most de minimis false arrest cases are “fees driven cases” (that is, the award of attorney’s fees will probably exceed the award to the plaintiff), most lawyers will not take state law false arrest cases.

Accordingly, because Justice Souter decided that he doesn’t want to burden police officers with having to determine if the crime that he found you in violation of is one that is an arrestable offense under state law, if the police have probable cause to believe that you violated any public offense, felony, misdemeanor of de minimis infraction (i.e. speeding, improper lane change, etc.), it does not violate the Fourth Amendment for the officer to take you to jail for any such violation.

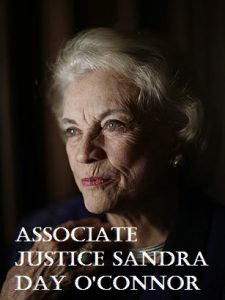

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a traditional Republic Conservative, appointed by President Ronald Reagan, railed against the Majority’s Opinion, hold that the Supreme Court was basically turning the United States into a police state:

In Atwater v. Lago Vista, a City of Lago Vista police officer arrested Gail Atwater for driving her truck in Lago Vista, Texas, with her small children in the front seat. None of them were wearing a seatbelt. City of Atwater police officer Bart Turek verbally berated Mrs. Atwater, handcuffed her, placed her in his squad car, and drove her to the local police station, where she was made to remove her shoes, jewelry, and eyeglasses, and empty her pockets.

Officers took her “mug shot” and placed her, alone, in a jail cell for about an hour, after which she was taken before a magistrate and released on bond. She was charged with, among other things, violating the seatbelt law.

She pleaded no contest to the seatbelt misdemeanors and paid a $50 fine. She and her husband (collectively Atwater) filed suit under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, alleging, inter alia, that the actions of respondents (collectively City) had violated her Fourth Amendment right to be free from unreasonable seizure.

The United States Supreme Court held that because Officer Turek had probable cause to arrest Mrs. Atwater, and there was no evidence the arrest was conducted in an extraordinary manner, unusually harmful to Atwater’s privacy interests, the court (Justice Souter) held the arrest not unreasonable for Fourth Amendment purposes.

Accordingly, a police officer can arrest one for anything that the law prohibits; anything at all.

Although under various state laws, such as in California, a peace officer can only give you a Citation and cannot take you to jail for a minor traffic infraction if you have sufficient identification, because in California state law claim for false arrest does not provide for an award of attorney’s fees, and because most de minimis false arrest cases are “fees driven cases” (that is, the award of attorney’s fees will probably exceed the award to the plaintiff), most lawyers will not take state law false arrest cases.

Accordingly, because Justice Souter decided that he doesn’t want to burden police officers with having to determine if the crime that he found you in violation of is one that is an arrestable offense under state law, if the police have probable cause to believe that you violated any public offense, felony, misdemeanor of de minimis infraction (i.e. speeding, improper lane change, etc.), it does not violate the Fourth Amendment for the officer to take you to jail for any such violation.

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a traditional Republic Conservative, appointed by President Ronald Reagan, railed against the Majority’s Opinion, hold that the Supreme Court was basically turning the United States into a police state:

Jerry L. Steering, Esq.“Under today’s holding, when a police officer has probable cause to believe that a fine-only misdemeanor offense has occurred, that officer may stop the suspect, issue a citation, and let the person continue on her way . . . . Or, if a traffic violation, the officer may stop the car, arrest the driver, . . . search the driver, . . . search the entire passenger compartment of the . . . car including any purse or package inside, see New York v. Belton, 453 U. S., at 460, and impound the car and inventory all of its contents . . . Although the Fourth Amendment expressly requires that the latter course be a reasonable and proportional response to the circumstances of the offense, the majority gives officers unfettered discretion to choose that course without articulating a single reason why such action is appropriate. Such unbounded discretion carries with it grave potential for abuse. The majority takes comfort in the lack of evidence of “an epidemic of unnecessary minor-offense arrests.” But the relatively small number of published cases dealing with such arrests proves little and should provide little solace. Indeed, as the recent debate over racial profiling demonstrates all too clearly, a relatively minor traffic infraction may often serve as an excuse for stopping and harassing an individual. After today, the arsenal available to any officer extends to a full arrest and the searches permissible concomitant to that arrest. An officer’s subjective motivations for making a traffic stop are not relevant considerations in determining the reasonableness of the stop. See Whren v. United States, supra, at 813. But it is precisely because these motivations are beyond our purview that we must vigilantly ensure that officers’ poststop actions—which are properly within our reach—comport with the Fourth Amendment’s guarantee of reasonableness. The Court neglects the Fourth Amendment’s express command in the name of administrative ease. In so doing, it cloaks the pointless indignity that Gail Atwater suffered with the mantle of reasonableness. I respectfully dissent. O’Connor, J.”

“Under today’s holding, when a police officer has probable cause to believe that a fine-only misdemeanor offense has occurred, that officer may stop the suspect, issue a citation, and let the person continue on her way . . . . Or, if a traffic violation, the officer may stop the car, arrest the driver, . . . search the driver, . . . search the entire passenger compartment of the . . . car including any purse or package inside, see New York v. Belton, 453 U. S., at 460, and impound the car and inventory all of its contents . . .

“Under today’s holding, when a police officer has probable cause to believe that a fine-only misdemeanor offense has occurred, that officer may stop the suspect, issue a citation, and let the person continue on her way . . . . Or, if a traffic violation, the officer may stop the car, arrest the driver, . . . search the driver, . . . search the entire passenger compartment of the . . . car including any purse or package inside, see New York v. Belton, 453 U. S., at 460, and impound the car and inventory all of its contents . . .