Dirty Harry and the Criminal Procedure Counter-Revolution.

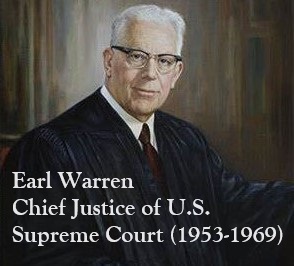

![Chief Justice Earl Warren]() The Criminal Procedure Revolution.

The Criminal Procedure Revolution.

Contrary to popular belief, the Bill of Rights, the first ten Amendments to the United States Constitution, was never intended to apply to the States. When the Bills of Rights were ratified by the States in 1791, the Bill of Rights was only supposed to be a restriction of power of the federal government. The States were free to ignore those protections provided for in the Bills of Rights until the Criminal Procedure Revolution of the 1960s.

Via the Doctrine of Selective Incorporation, the Supreme Court held some, but not all of the provisions of the Bill of Rights binding on the State. It was not until 2010 that the Second Amendment’s Right to Bear Arms was made obligatory on the States in McDonald v. Chicago, 561 U.S. 742 (2010); again through the liberal Doctrine of Selective Incorporation.

The Criminal Procedure Revolution and the Exclusionary Rule.

What we now know as the Fourth Amendment exclusionary rule did not apply to the States until 1961 in Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961). The Fourth Amendment Exclusionary Rule simply holds that evidence that is obtained by the police pursuant to an illegal search and seizure of a criminal defendant, his/her effects or his/her home, cannot be used by the prosecution against the defendant at his/her criminal trial. Mapp v. Ohio was the beginning of the Warren Court’s Criminal Procedure Revolution.

Prior to 1961, the States were not prohibited from using illegally obtained evidence at criminal trials. Following Mapp v. Ohio, the Warren Court issued a series of Selective Incorporation Decisions, incorporating and making binding the States various other provisions of the Bill of Rights, to wit:

The Sixth Amendment’s Right to Counsel Clause first became binding on the States in 1963 Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963).

The Fifth Amendment’s Right against Self-Incrimination Clause first became binding on the States in 1964 in Malloy v. Hogan, 378 US 1 (1964).

The Sixth Amendment’s Right to Confront Your Accusers, the Right to Cross-Examine hostile witnesses, first became binding on the States in incorporated in 1965 in Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965)

The Sixth Amendment’s Right to an Impartial Jury first became binding on the States in 1966 in Parker v. Gladden, 385 U.S. 363 (1966).

The Fifth Amendment’s Right Against Self-Incrimination and the Sixth Amendment’s Right to Counsel’s protection against Coercive Police Interrogations first became binding on the States in 1966 in Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966).

The Sixth Amendment’s Right to a Speedy Trial first became binding on the States in 1967 in Klopfer v. North Carolina, 386 U.S. 213 (1967).

The Sixth Amendment’s Right to Compulsory Process to obtain favorable witness testimony first became binding on the States in 1967 in Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1967).

The Fifth Amendment’s “Double Jeopardy Clause” was first made binding on the states in 1969 in Benton v. Maryland, 395 U.S. 784 (1969).

These landmark decisions of the Supreme Court we take for granted today.

The Criminal Procedure Counter-Revolution.

In 1969, President Richard Nixon appointed Warren Burger Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in place of the retiring Chief Justice, Earl Warren. Chief Justice Burger led the Supreme Court to overturn and reject many of the Criminal Procedure Decision of the Warren Court. This happened in large part due to the Exclusionary Rule, as the Justices and the public were not sympathetic to watching the “guilty go free because the Constable has blundered“.

Because of the Exclusionary Rule, many Americans came to believe that the Courts are a bunch of “liberal judges” who let the criminals go free for the slightest technicality. This is not reality, but what does reality have to do with politics. In politics, perception is reality.

Dirty Harry and the Criminal Procedure Counter-Revolution

In Clint Eastwood’s 1971 movie “Dirty Harry”, a psychopathic sniper named “Scorpio”, shoots a woman while she swims in a San Francisco skyscraper rooftop pool. He leaves behind a threatening letter demanding he be paid $100,000 or he will kill more people. The note is found by SFPD Inspector Harry Callahan, who is investigating the killing. The mayor teams up with the police to track down the killer, although to stall for time, he agrees to Scorpio’s demand over Callahan’s objections.

In Clint Eastwood’s 1971 movie “Dirty Harry”, a psychopathic sniper named “Scorpio”, shoots a woman while she swims in a San Francisco skyscraper rooftop pool. He leaves behind a threatening letter demanding he be paid $100,000 or he will kill more people. The note is found by SFPD Inspector Harry Callahan, who is investigating the killing. The mayor teams up with the police to track down the killer, although to stall for time, he agrees to Scorpio’s demand over Callahan’s objections.

A doctor who treated Scorpio phones the police and tells Callahan and his new partner, Frank DiGiorgio (John Mitchum), that he has seen Scorpio before, and that he thinks that Scorpio (the wounded man that he treated for the stab wound), works at and has a bed room in Kezar Stadium. Running out of time, Callahan and his new partner break into Scorpio’s stadium living quarters; looking for Scorpio and/or evidence of the buried girls whereabouts, finds the rifle that Scorpio used to kill the girl on the roof top pool, and see Scorpio running away, on the football field itself. Inspector Callahan then shoots the fleeing Scorpio in his already stab-wounded leg (with his .44 Magnum revolver.)

When Scorpio refuses to reveal the location of the girl and demands a lawyer, Callahan tortures the killer, by standing on and grinding Scorpio’s wounded leg until he reveals the girl’s whereabouts. However, by the time that the SFPD is able to go to the girl’s burial site, they find her dead; suffocated.

Because Callahan searched Scorpio’s home (a live-in custodian’s room at a local football stadium) without a warrant and “improperly” seized his rifle, the District Attorney tells Inspector Callahan, that the killer cannot be charged with the murder of the girl in the rooftop swimming pool, because that rifle that was used to shoot her was found by Callahan in Scorpio’s lair was seized in violation of Scorpio’s Fourth Amendment rights.

The screenplay claims that because “Dirty Harry” located and seized the rifle without a search warrant, that it’s now inadmissible as evidence in court against Scorpio. The District Attorney also tells Inspector Callahan that they can’t even prosecute Scorpio for the murder of the buried girl, because her body was found as the product of “Dirty Harry” torturing the girl’s whereabouts out of Scorpio.

This advisement that the search was unlawful, was reiterated by a California Court of Appeal Judge, who is seen sitting in the San Francisco District Attorney’s Office, advising the DA and Inspector Callahan, that the evidence was inadmissible in court against Scorpio (Appellate Judges just don’t hang-up with the DA; at least until after they retire.)

When the DA and the Judge tells Dirty Harry that the law dictates that the evidence is inadmissible in court against Scorpio, Dirty Harry retorts that he didn’t have time to get a search warrant (which he didn’t.) When the DA tells Callahan, too bad; Scorpio walks; that’s the law, Dirty Harry tells the DA “then the law is crazy”, and is taken off of the case; warning that Scorpio will kill again (in the film Scorpio later kidnapped a school bus full of children at gunpoint, and ended-up getting his “head blown clean off” by Dirty Harry’s .44 Magnum revolver; “The Most Powerful Handgun In The World”.)

Moreover, under the scenario described above, the search by Dirty Harry wasn’t unlawful at all. There was no time for Inspector Callahan to have sought a search warrant, because “Scorpio” was telling the police that the kidnapped girl only had an hour or two of air left in her buried prison, and evidence of the girl’s whereabouts might be found in Scorpio’s living quarters at the stadium. However, Dirty Harry wouldn’t be Dirty Harry if he didn’t step on a few Constitutional Rights to achieve curbside justice.

So, the viewing audience is now convinced that “liberal judges” have created Constitutional prohibitions against seemingly reasonable police conduct. Their view of the Constitution has been distorted, because the viewers are led to believe that “the law is crazy”, and that police officers who ignore Constitutional constraints on their conduct are in the right, and heroes for doing so. Lesson learned by the body politic; the Constitution contains stupid technicalities created by liberal Judges, that stand in the way of public safety and justice itself.

Unfortunately, since most Americans learn criminal procedure by watching dramas, the voters, who elect the politicians, who appoint most of the state court Judges, and all federal (Article III) Judges (i.e. United States District Judges, all Judges of the United States Court of Appeals, and the Justices of the United States Supreme Court.) As a result, in California criminal cases, the Appellate Courts very often distort and pervert (i.e. actually change, via judicial fiat,) the contours the protections provided for in the United States Constitution, by simply stating that the Constitution doesn’t prohibit a particular form of government conduct (anymore, or ever), so they don’t have to exclude evidence in a criminal trial; evidence that will often prove the defendant’s guilt, and without which, the government has no case.

This, unfortunately, is the unintended consequence of the exclusionary rule; the rule created by the United States Supreme Court, to curb unconstitutional police conduct, by excluding evidence obtained in violation of the defendant’s Constitutional rights.

When Judges are faced with a choice of either excluding incriminating evidence at criminal trial because it was obtained in violation of the federal Constitution (or in many states, the state Constitution), or simply reinterpreting (changing) the protection that a particular constitutional provision provides, Appellate Court Judges often change the protections of the applicable Constitutional provision (i.e. usually 4th, 5th and 6th amendment rights), to let the evidence in. Although this may be just wonderful for convicting the guilty, the consequences of reducing the protections afforded to all persons under a particular Constitutional provision, undermines the liberty interests of the rest of us innocent people:

“By the Bill of Rights the founders of this country subordinated police action to legal restraints, not in order to convenience the guilty but to protect the innocent. Nor did they provide that only the innocent may appeal to these safeguards. They knew too well that the successful prosecution of the guilty does not require jeopardy to the innocent. The knock at the door under the guise of a warrant of arrest for a venial or spurious offense was not unknown to them. Compare the statement in Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383, 390, 34 S.Ct. 341, 343 (1913) , that searches and seizures had been made under general warrants in England ‘in support of charges, real or imaginary.’ We have had grim reminders in our day of their experience. Arrest under a warrant for a minor or a trumped-up charge has been familiar practice in the past, is a commonplace in the police state of today, and too well-known in this country. See Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U.S. 451, 59 S.Ct. 618, 83 L.Ed. 888. The progress is too easy from police action unscrutinized by judicial authorization to the police state. The founders wrote into the Constitution their conviction that law enforcement does not require the easy but dangerous way of letting the police determine when search is called for without prior authorization by a magistrate. They have been vindicated in that conviction. It may safely be asserted that crime is most effectively brought to book when the principles underlying the constitutional restraints upon police action are most scrupulously observed.” United States v. Rabinowitz, 339 U.S. 56 (1950), (Frankfurter, J.)

Sorry ladies and gentlemen; the very tool fashioned by the United States Supreme Court since 1914 to dissuade Constitutional violations against civilians by peace officers, the Exclusionary Rule, has backfired. In 1914 in Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914) the Supreme Court stated:

“The tendency of those executing Federal criminal laws to obtain convictions by means of unlawful seizures and enforced confessions in violation of Federal rights is not to be sanctioned by the courts which are charged with the support of constitutional rights.

The Federal courts cannot, as against a seasonable application for their return, in a criminal prosecution, retain for the purposes of evidence against the accused his letters and correspondence seized in his house during his absence and without his authority by a United States marshal holding no warrant for his arrest or for the search of his premises.

While the efforts of courts and their officials to bring the guilty to punishment are praiseworthy, they are not to be aided by sacrificing the great fundamental rights secured by the Constitution.”

That is the real birth of the great exclusionary rule. It is virtuous, and it is the right decision. The exclusionary rule was first applied to the states, via the selective incorporation doctrine, in 1961 in Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961.)

It has caused the various state and federal Appellate level courts, and the state and United States Supreme Court, to go along with hacking away your basic Constitutional protections against police seizure, harassment and oppression of you, in order to allow the introduction of evidence at criminal trials.

Imagine a hypothetical situation where the Judge presides over a rape and murder case, involving the rape and murder of a young girl by a middle-age man, with overwhelming evidence that the man is guilty. The defendant claims that the evidence that also proves his guilt, was obtained in violation of his federal constitutional rights. The Judge is then faced with the choice of either: 1) finding that there was a constitutional violation, which would require that Judge to exclude the introduction of that evidence at trial, or, 2) simply finding that the conduct of the police complained of by the defendant, was no constitutional violation at all. Which one do you think that the trial court is going to choose?

Also assume that the only logical conclusion from undisputed evidence, like a police video, is that the police committed a violation of federal constitutional law in obtaining that “smoking gun” evidence, and the constitutional violation is based on Supreme Court cases that make that principal “clearly established law”. If the Judge (the one who let all of the TV cameras in his courtroom) followed then existing Constitutional Jurisprudence on an issue of federal constitutional law, generally, the Judge must exclude that “smoking gun” evidence at trial. How popular is that Judge going to be with his TV and media audience if he granted the obviously guilty defendant’s motion to suppress the evidence? What are that Judge’s chances of reelection, if he lets an obviously guilty child rapist and murdered go free?

That’s why federal judges are appointed by the President, and approved by the United States Senate, for life. They can’t be fired; they may only be removed upon a Bill of Impeachment being presented to the Senate, and the Senate, holding a trial of that Bill; determining whether or not to remove that judge from office. That doesn’t mean that all federal judges are now kind and understanding. But it does mean that they don’t have to be a political weather vanes. Nonetheless, the great remedy has “collateral damage”; your and mine protection from government oppression.

“Dirty Harry” was right; the law is crazy. It’s also somewhat of a scam, albeit the best one on this earth.

LAW OFFICES OF JERRY L. STEERING

Jerry L. Steering, Esq.

Published: 2/5/2019

The Criminal Procedure Revolution.

The Criminal Procedure Revolution.