THE SHAM AND SCAM OF DISCOVERY IN CALIFORNIA CRIMINAL CASES.

![JLS in Courtroom cropped 2]() Most, If Not All, Police Agencies Destroy Or Conceal Exculpatory Evidence, When Their Officers Abuse Civilians And Procure Their Bogus Criminal Prosecutions. Police Officers and Their Agencies Routinely Conceal and Destroy Exculpatory Evidence When They Violate Your Constitutional Rights.

Most, If Not All, Police Agencies Destroy Or Conceal Exculpatory Evidence, When Their Officers Abuse Civilians And Procure Their Bogus Criminal Prosecutions. Police Officers and Their Agencies Routinely Conceal and Destroy Exculpatory Evidence When They Violate Your Constitutional Rights.

The Genesis Of The Problem Of Police Arresting Their Victims – Terry v. Ohio.

First, we all acknowledge that there really are honorable, decent, brave and virtuous, men and women of the law enforcement profession, at all levels. The actual risk of physical injury by working as a peace officer is usually greatly exaggerated, but as George Orwell pointed out:

“Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.”

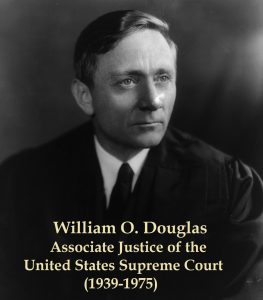

As discussed in other articles in this website, the exaggeration of that risk of danger to police officers, and the policy decisions by the courts in allowing “Officer Safety” to trump your and my Constitutional Rights, has lead to the police being excused from the traditional constraints on their power (i.e. the Fourth Amendment’s proscription of unreasonable searches and seizures), to, as a practical matter, being able to seize the individual at their whim. As Justice William O. Douglas had the courage and foresight to profess in Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) where, for the first time in the history of the Republic, the United States Supreme Court approved the seizure of a free citizen on less than “probable cause” to believe that the person had committed a crime:

“The opinion of the Court disclaims the existence of “probable cause.” If loitering were in issue and that was the offense charged, there would be “probable cause” shown. But the crime here is carrying concealed weapons; [n2] and there is no basis for concluding that the officer had “probable cause” for believing that that crime was being committed. Had a warrant been sought, a magistrate would, therefore, have been unauthorized to issue one, for he can act only if there is a showing of “probable cause.” We hold today that the police have greater authority to make a “seizure” and conduct a “search” than a judge has to authorize such action . . .

“The opinion of the Court disclaims the existence of “probable cause.” If loitering were in issue and that was the offense charged, there would be “probable cause” shown. But the crime here is carrying concealed weapons; [n2] and there is no basis for concluding that the officer had “probable cause” for believing that that crime was being committed. Had a warrant been sought, a magistrate would, therefore, have been unauthorized to issue one, for he can act only if there is a showing of “probable cause.” We hold today that the police have greater authority to make a “seizure” and conduct a “search” than a judge has to authorize such action . . .

. . . To give the police greater power than a magistrate is to take a long step down the totalitarian path. Perhaps such a step is desirable to cope with modern forms of lawlessness. But if it is taken, it should be the deliberate choice of the people through a constitutional amendment. [p39] Until the Fourth Amendment, which is closely allied with the Fifth, [n4] is rewritten, the person and the effects of the individual are beyond the reach of all government agencies until there are reasonable grounds to believe (probable cause) that a criminal venture has been launched or is about to be launched.

We have said precisely the opposite over and over again. [n3] Yet if the individual is no longer to be sovereign, if the police can pick him up whenever they do not like the cut of his jib, if they can “seize” and “search” him in their discretion, we enter a new regime. The decision to enter it should be made only after a full debate by the people of this country.” Douglas, J., Dissenting.

That all being said, because of the relaxation of Constitutional constraints on the police by the courts since 1968, the police have so much power, that many of them cannot resist abusing that awesome power.

As Lord Acton’s famous quote goes: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Most great men are bad men.”

As Lord Acton’s famous quote goes: “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Most great men are bad men.”

The power that Terry v. Ohio gave the police is simply too much for many police officers to handle. For example, in Terry v. Ohio, for the first time in the history of the Republic, the Supreme Court “gave” the police the power to stop and frisk a person whom the police officer, based on articulable facts: 1) had a reasonable suspicion that crime “may be afoot” (“criminality afoot“), 2) that a particular person is suspected of being involved in that crime, and 3) he person suspected is armed and dangerous. A “stop and frisk” is also known as a “Terry stop.” A judge cannot issue a warrant for a person to be detained for questioning. There is no such thing as a detention warrant.

Terry v. Ohio was never meant to allow detentions of persons who were suspected of criminal activity and were not reasonably believed to have been armed and dangerous. See, Stop and Frisk Laws,Panelists discussed the Terry v. Ohio case, which dealt with law enforcement and police citizens encounters, C-SPAN Video, April 2, 1998. However, implicit in Terry’s stop and frisk of civilians is the ability of the police to detain that person. The police cannot frisk someone without in some way temporarily restricting their freedom to ignore the presence of the officer and to go about their business. They can’t pat them down on the run.

However, as always, give them an inch and they’ll take a mile. Accordingly, the “long step down the totalitarian path” was the Supreme Court’s departure from 177 years of American jurisprudence that required the government to have “probable cause” to believe that you committed a crime to restrain your liberty.

A “stop and frisk” is also known as a “Terry stop.”A judge cannot issue a warrant for a person to be detained for questioning. There is no such thing as a detention warrant.

So, the Supreme Court has given the police more power than a judge. The outcome of that endowment of police power, is the modern nationwide tsunami of acts of police abusing the public; usually for nothing other than their assertion of their Constitutional rights, or verbal challenge to unreasonable police orders to them. When a police officer abuses a civilian, the reaction of every police agency that this author has dealt with since 1984, isn’t to actually investigate the officer, but to put into motion the machinery of police agency damage mitigation; to shift the blame to the civilian who is the victim of police abuse.

Because, as a practical matter, the police have unfettered discretion stop you, to point a gun at you, to handcuff you, to search your person, to make you sit or prone on the ground, and to do other nasties to you, police officer often will arrest you for conduct that isn’t a crime; usually when you question or challenge their authority, or don’t do what they order you to do, without question or protest. When they do so, the violating police officer, his/her employing agency, and the violating officer’s fellow employees, are all now put in a position of either being honest and forthcoming (i.e. telling what really happened in their supplemental report, keeping and maintaining exculpatory evidence, and divulging exculpatory evidence), or being a “team player” (i.e. lying in their supplemental reports about what really happened, or destroying or concealing exculpatory evidence.) Otherwise honest cops are left with a choice of either implicating their fellow officers in crimes and constitutional torts, or telling the truth, and being driven out of their employing police agency. If the officer tells the truth, and implicates a fellow officer, his/her career is, for all practical purposes, over. There is always tremendous institutional pressure for a police agency that arrested you for a crime that you didn’t commit, to shift the blame to you. This is reality.

In the practical way that the real world works, when it comes to choosing between the Constable’s career either ascending or descending, or whether they’re willing to be labeled as a “rat” and still work every day with cops who will hate their guts for telling the truth, we all know which choice is going to be made by the Constable. So, we have a society in modern America, that actually encourages police officers to abuse and frame innocents; usually for committing what is know in law enforcement circles as “Contempt of Cop“. “Contempt of Cop” often results in a person being arrested for bogus offenses, such as:

1) Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1); Resisting / obstructing / delaying a peace officer;

2) Cal. Penal Code § 69; Use of violence or threat of violence, to prevent, or to attempt to prevent public officer from lawfully performing duty;

3) Cal. Penal Code § 242/243(b); Battery on a peace officer; and

4) Cal. Penal Code § 240/241(c); Assault on a peace officer.

It is these offenses, known as “Resistance Offense”, that persons who are falsely arrested are usually arrested for, and that police most often conceal or destroy exculpatory evidence in connection with.

CONCEALMENT AND DESTRUCTION OF EXCULPATORY EVIDENCE BY POLICE AND PROSECUTORS.

This effort by the police, to conceal exculpatory evidence from you, is basically twofold:

In the first instance, where the very policies, customs and practices of the involved police agency leads to concealing exculpatory evidence from both the District Attorney’s Office, and, therefore, also from the criminal defendant.

In the second instance, where an individual police officer or deputy sheriff simply conceals or destroys exculpatory evidence. Both of these practices are very real and very commonplace.

This is not some lefty Socialist Worker’s Party propaganda; this is a simple matter of truth, justice and the American way; at least what we’re taught is the American way. See, Judge Kozinski on prosecutorial misconduct, Washington Post, July 17, 2015.

For example, under the California discovery scheme, the defendant has a right to the discovery of the statements of witnesses who the prosecution intends to call at trial. Cal. Penal Code § 1054.1 However, notwithstanding that clear mandate of Section 1054.1, more often than not, even though the police know that items like police “Deputy / Officer Daily Activity Reports”, “Use of Force Investigation” packages, “Patrol Sergeant’s Daily Reports“, Deputy / Officer emails to each other and to supervisors, Intra-Departmental Memos, BOLO’s (be on look out for) and as especially the Internal Affairs investigation of the very incident complained of; something that contains the statements of the very witnesses that the prosecution intends to call at trial (i.e. the arresting officer who beat you up.)

These Internal Affairs Investigation files are not only kept secret from the accused, but also from the District Attorney’s Office;literally disabling the District Attorney’s Office from complying with their obligations under Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963). See, How a Man Named Brady Made History 50 Years Ago. New York Law Journal, May 13, 2013.

To even make things worse, in People v. Superior Court, S221296, Cal. Supreme Court (2015), the California Supreme Court held that in California Public Prosecutors comply with the state’s duty to provide exculpatory to a criminal defendants by waiting for police “tips” that a particular peace officer in a particular case might have evidence in their personnel records that may be exculpatory. Sorry folks, but the police are the last people in the world to give anyone any such tips:

“Because criminal defendants and the prosecution have equal ability to seek information in confidential personnel records , and because such defendants, who can represent their own interests at least as well as the prosecution and probably better, have the right to make a Pitchess motion whether or not the prosecution does so, we also conclude that the prosecution fulfills its Brady duty as regards the police department‘s tip if it informs the defense of what the police department informed it, namely, that the specified records might contain exculpatory information. That way, defendants may decide for themselves whether to bring a Pitchess motion.

Unfortunately, most criminal lawyers (who don’t sue police officers) have limited knowledge of what types of evidence is “out there”, to improve their odds of success in their trials and motions. The Judges, both trial and appellate, have this attitude, that because you’re being criminally prosecuted, that you should have less discovery rights when your freedom and your life is at stake, than if you sued your neighbor about making rude remarks to you.See, Haggerty v. Superior Court, 12 Cal.Rptr.3d 467 (2004.)

This has to change. Moreover, as shown below, the cops simply lie through their teeth, and don’t give-up any “juice” against them, unless they conclude that they are going to get caught if they ditch the evidence. However, even if they do get caught, nothing is going to happen to them. Nothing.

Moreover, the prosecution routinely claims that they defendant should have certain discovery because they’re engaged in a “fishing expedition.” Really? No kidding? That’s exactly what discovery is. If you already knew what you were asking for, they wouldn’t call it “discovery.”

THE “BRADY RULE” AND PROPOSITION 115.

Because of the United States Supreme Court case of Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963), a police agency or prosecutorial agency (i.e. the State Attorney General’s Office, a County District Attorney’s Office, a City Attorney’s Office, the United States Attorney’s Office / United States Department of Justice. etc.) must notify a criminal defendant about any “exculpatory evidence” (i.e. evidence that either tends to show that the defendant is innocent, or evidence that can be used to impeach a witness’ character for honesty) that it knows of. In California criminal cases, the defendant can only obtain pre-trial discovery (i.e. police reports, patrol video and audio recordings, probable cause for warrantless arrest declarations, radio recordings, activity reports, use of force reports, etc.) by first making “informal” discovery demands (i.e. a letter) to the District Attorney’s Office, and cannot directly subpoena the investigating or arresting police agency to produce items of evidence. See, Cal. Penal Code § 1054(e) (” . . . no discovery shall occur in criminal cases except as provided by this chapter, other express statutory provisions, or as mandated by the Constitution of the United States”), and Cal. Penal Code § 1054.5:

“This chapter shall be the only means by which the defendant may compel the disclosure or production of information from prosecuting attorneys, law enforcement agencies which investigated or prepared the case against the defendant, or any other persons or agencies which the prosecuting attorney or investigating agency may have employed to assist them in performing their duties.”

This all came about as a result of the Glendale Doctor Murder Case, in which there was a six month long preliminary examination. Because of that six month long preliminary examination, the voters had enough of the “wasting of their money” by continuing to give those accused of crimes their fundamental rights, such as the right to confront their accusers, such as the right to “confront” (i.e. cross-examine) those witnesses accusing the defendant of a crime (a Sixth Amendment right), to decide whether the prosecution can show sufficient evidence to even have a felony trial. The right to a preliminary examination exists to weed-out meritless felony cases, so a person need not have to suffer the expense and degrading experience of have to defend themselves in a felony trial.

Prior to Proposition 115 (the “Crime Victims Justice Reform Act” of 1990), a person had a right to have non-hearsay evidence presented at their preliminary examination, so they could cross-examine the witnesses. So, for example, if your neighbor told the police that you stole his car, and you got arrested for auto theft, at your preliminary examination, the “victim” had to personally testify about what happened, and was subject to cross-examination. Now, with Prop 115, all that the prosecution need do, is to put a cop on the stand who is “Prop 115 qualified“, who then tells the judge, what he saw, and what everyone else told him (hearsay.) The cop can even testify as to what’s contained in another officer’s police report. You can’t cross-examine a police report, and you can’t cross-examine a witness who isn’t there. You might as well just give the police report to the judge, and let him rule based strictly on the report, because, in essence, that’s what’s going on; all under the guise of “reform”.

This wave of “reform” (Proposition 115) was part of former California Governor Pete Wilson Gubernatorial Campaign in 1990, that lead to his election that year. No longer would those being accused of felonies (those pesky criminal defendants that costs us honest folks so much money.)

Accordingly, under Brady and its progeny, if any such police or prosecutorial agency is aware of acts of dishonesty by a police officer, or other actions by a peace officer, or complaints made or actions (lawsuits) brought against a peace officer that may be exculpatory in a particular case (i.e. acts of excessive force showing that the officer “gooned” a civilian, that may tend to show that he used excessive force during the incident complained of; and is defense to a “contempt of cop” type crime), such evidence must be disclosed to the criminal defendant’s lawyer; even the absence of a request for such evidence by any such criminal defendant. The prosecutorial agency is deemed to be the same as the police, for this evidentiary constitutional mandate. Kyles v. Whitely, 514 U.S. 419 (1995.)

However, there “glitches” with this system.

FIRST “GLITCH” IN CALIFORNIA’S STATUTORY CRIMINAL DISCOVERY SCHEME; PLAUSIBLE DENIABILITY.

BECAUSE “PLAUSIBLE DENIABILITY” IS INHERENT IN CALIFORNIA’S STATUTORY DISCOVERY SCHEME, THE POLICE CAN, AND DO, LIE THROUGH THEIR TEETH TO THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE, ABOUT WHAT EVIDENCE EXISTS, AND WHAT DOESN’T.

If you can’t subpoena the custodian of records from the investigating or arresting agency, the Deputy District Attorney simply stands in court and tells the judge that the police agency told him that no such documents or recordings exist, and the judge tells the defense lawyer, “Well, there you go. Next case please.”

In fact, the criminal defense lawyer needs to subpoena the custodian of records and/or the person with the investigating and arresting agency to the motion to compel discovery, and put them to task; make them testify as to whether any such items of discovery exist, and, if so, where are those items. Some judges won’t permit viva voce testimony at these hearings (mainly, because they’re creepy and/or they feel that they have to protect the cops, or they just don’t know any better.)

The criminal defendant’s lawyer makes “informal” discovery requests upon the District Attorney’s Office (or State Attorney General’s Office or City Attorney’s Office; who ever is prosecuting the case), pursuant to Cal. Penal Code §§ 1054.1 and 1054.5. The District Attorney’s Office forward’s the defendants discovery request to the arresting and/or investigating police agency (if you’re lucky, and when they get around to it), who then supposedly looks for the requested evidence, and then supposedly produces the same to the District Attorney’s Office. The police tell the District Attorney’s Office that they don’t have certain items of evidence, but, in almost every case, they actually do; usually lots of other evidence. This is no joke.

Then, after being denied the requested discovery, the defendant’s lawyer files a Motion to Compel Discovery with the Superior Court. The Judge then makes rulings on compelling the disclosure of certain items of evidence, and, very often, will simply take the DA’s or police agency’s word that certain items don’t exist. If, somehow, the criminal defendant can prove that these type of documents are routinely used by that particular police agency, the defendant’s lawyer may be able to convince a judge to issue an order compelling the production of the sought evidence. However, many Judges are either just too “pro-police”, or too scared that they won’t get the police union’s endorsement when they have to run for reelection, to issue such discovery orders, when the DA’s office or police agency tells him that the requested items don’t exist. Thus, the system is rigged against the criminal defendant.

In a recent case handled by Law Offices of Jerry L. Steering Associate Attorney Gregory Paul Peacock, People v. Osborne (Rancho Cucamonga – San Bernardino County Superior Court), Mr. Osborne was accused of violation of Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1); resisting / obstructing / delaying a peace officer engaged in the performance of his/her duties, for refusing to consent to a warrantless search of his home in Upland, California. The police also gooned Mr. Osborne, and arrested him; notwithstanding that there was clearly established law that a refusal to consent to a warrantless search is never a crime. See, People v. Wetzel , 11 Cal.3d 104 (1974) (defendant’s refusal to move out of doorway of her home, even when police had legal right to pursue fleeing suspect inside home, not a crime.) See also, See v. City of Seattle, 387 U.S. 541 (1967) and Camara v. Municipal Court, 387 U.S. 523 (1967) (both cases holding no crime to refuse consent for warrantless search by police.)

On June 7, 2013, at Mr. Osborne’s Motion to Compel Discovery in that criminal case, the prosecution represented to the Court that there was no audio recording of the incident complained of in that action by Upland Police Department Officer Boyle. Officer Boyle was sitting right there, but said nothing. The Court told Mr. Peacock that unless he could prove that there was an audio recording of the incident made by Officer Boyle (something apparent from the minute and second reference in Officer Boyle’s police report), that the Court would deny Mr. Osborne’s motion to compel the production of the alleged recording. Mr. Peacock then called Officer Boyle to the witness stand, and to everyone’s shock and disbelief, Officer Boyle actually testified that he audio recorded the entire incident (See, Reporter’s Transcript of Oral Proceedings in People of the State of California v. Osborne; San Bernardino County Superior Court.)

Many times, the police are either too lazy to do their job (i.e. locate and produce the evidence to the District Attorney’s Office), or too corrupt to produce evidence that they believe might result in either the acquittal of the criminal defendant, or might otherwise implicate the police agency in misconduct; especially misconduct that might expose the employing municipal entity to civil liability (Yes, police agencies really do that routinely; just like in the Osborne case, above.) Who is going to either care, or do anything about the police routinely and quite deliberately, withholding exculpatory evidence? Jerry Brown? Kamala Harris? Eric Holder? Kofi Annan? The Pope? Santa Claus? The answer is, nobody.

The overwhelming majority of cases handled by the Law Offices of Jerry L. Steering involve police officers and deputy sheriffs who have committed acts of dishonesty (i.e. false testifying in depositions in civil rights cases, falsely testifying in court, authoring false and misleading police reports), or have committed other acts that can be used to show a criminal defendant’s innocence (i.e. a pattern of beating-up innocents and then framing or attempting to frame them.) Moreover, because The Law Offices of Jerry L. Steering sues cops, Mr. Steering has obtained in civil discovery (i.e. depositions, document production demands and interrogatories), much more and different types of police agency documents and items of evidence, that a regular lawyer who only does criminal cases doesn’t know exist. We can help you significantly with your criminal case in this way; knowing what evidence is available from a particular police agency.

SECOND “GLITCH” IN STATUTORY DISCOVERY SCHEME; INTENTIONAL POLICE DESTRUCTION POTENTIALLY OR ACTUALLY EXCULPATORY EVIDENCE BY POLICE AGENCIES IS “LEGAL”.

Cal. Gov’t Code § 26202.6 provides for the retention periods for audio recordings of police department radio and telephone (i.e. 911 calls) communications (and for routine video monitoring (i.e. fixed video camera recordings, such as surveillance videos at a jail), for a minimum of 100 days:

“26202.6. (a) Notwithstanding the provisions of Sections 26202, 26205, and 26205.1, the head of a department of a county, after one year, may destroy recordings of routine video monitoring, and after 100 days may destroy recordings of telephone and radio communications maintained by the department. This destruction shall be approved by the legislative body and the written consent of the agency attorney shall be obtained. In the event that the recordings are evidence in any claim filed or any pending litigation, they shall be preserved until pending litigation is resolved.”

Cal. Gov’t Code § 34090.6 provides for the retention periods for audio recordings of sheriff’s department radio and telephone (i.e. 911 calls) communications (and for routine video monitoring (i.e. fixed video camera recordings, such as surveillance videos at a jail), for a minimum of 100 days:

“34090.6. (a) Notwithstanding the provisions of Section 34090, the head of a department of a city or city and county, after one year, may destroy recordings of routine video monitoring, and after 100 days may destroy recordings of telephone and radio communications maintained by the department. This destruction shall be approved by the legislative body and the written consent of the agency attorney shall be obtained. In the event that the recordings are evidence in any claim filed or any pending litigation, they shall be preserved until pending litigation is resolved.”

This 100 day retention period is not an arbitrary date. The California Tort Claims Act of 1963 provided that in order to make a claim for damages against a California public employee, acting in the course and scope of their employment, and/or against the public employee’s employing entity, a damaged party had 100 days to file a Government Tort Claim with the employing public entity. That’s why the retention period for audio recordings of radio and telephone communications was 100 days. However, when the

Government Tort Claim period was enlarged to 6 months, the geniuses in Sacramento forgot about Section 26202.6 and 34090.6, and failed to also enlarged those retention periods to six months. However, most municipal entities became aware of this discrepancy and changed their retention period to six months or more.

CAUTION: THESE RETENTION PERIODS ARE OFTEN MISREPRESENTED IN COURT BY THE DISTRICT ATTORNEY’S OFFICE.

It’s not that the District Attorney’s Office is lying. Because of the insidious way that pre-trial discovery works in California state court criminal prosecutions, perfectly honest Deputy District Attorneys simply stand-up in court, and tell the judge that she/he spoke with the involved police agency, and that some nice Detective or Evidence / Records Clerk at the police agency, told her that the recordings and documents sought, just don’t exist. End of story. Ninety percent of discovery disputes in California State Court criminal proceedings are basically handled that way. So, when you get-up in court, and want to obtain the audio recordings of 911 call that prompted the dispatcher to summons the patrol officer, jurisdictions such as the Riverside Sheriff’s Department will tell you that they have recently enlarged their retention period, from six months, to eight months.

Although the six moth retention period may have been justifiable when audio recordings was actually recorded on tape, now, the telephone and radio communications for a department for an entire year can be stored on a thumb drive. There is no reason to destroy them at all. The justification in past for “recycling” the radio and telephone communications tapes, was the fact that they were tapes that took-up a lot of space; not so for digital media. Nowadays, you can store the entire year’s worth of audio recordings of radio and telephone communications on a thumb drive.

Notwithstanding that reality, until March of 2012, the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department’s Official written policy on the retention of Sheriff’s Department analog and digital audio recordings of Sheriff’s Department “911” communications and Sheriff’s Department radio communications, was six months; the same period for a person to make a California Tort Claim (Cal. Gov’t Code § 910 et seq.) Now, the retention period is 8 months, even thought the justification in past for “recycling” the radio and telephone communications tapes, was the fact that they were tapes that took-up a lot of space; not digital media. Nowadays, you can store the entire year’s worth of audio recordings of radio and telephone communications on a thumb drive, so why only 8 months? Because if the police have a recording that supports their position in a civil or criminal case, the audio recording is not purged, and if the audio recording would tend to undercut their position in a case, it either actually gets “purged”, or the cops claim that it was “purged.”

Moreover, this is so, even though the statute of limitations to file a misdemeanor is one year, and three years for a felony. So, if the cops really want to play dirty, they can wait six months, wait and see if you file a Government Tort Claim for Damages, and then, if you do, they can “flush” the recordings of the very radio dispatch upon which they relied in detaining you to begin with, and proceed to prosecute you; to beat you down and to preclude you from successfully prosecuting your civil claim. Also, since the 100 day retention period is still in effect, if the criminal defense attorney doesn’t make a formal demand on the police agency to preserve those recordings within the 100 day period, and the cops “purge” or the recordings, too bad for you. See, Fowler v. Superior Court, 162 Cal. App.3d 215 (1984.) This is so, even if there is a pending criminal case against you; something prohibited by the language of Sections 26202.6 and 34090.6, because the Fowler Court held that police shouldn’t have to monitor their cases, to see which ones are being prosecuted. So, if you’re being prosecuted for resisting a detention by a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1)), and the cops legal basis for detaining you is the radio dispatch that they received about someone who the police were told committed a crime, if your lawyer doesn’t make a formal preservation demand on the arresting police agency for the audio recordings of radio or telephone communications, the criminal defendant simply is put in a position of not being able to refute that basis for their detention (the radio dispatch communication), because of the police agency’s retention policy.

THIRD “GLITCH” IN STATUTORY DISCOVERY SCHEME; DISCOVERY OF PEACE OFFICER PERSONNEL RECORDS IN CRIMINAL CASES.

After the Pitchess decision came down in 1974, police agencies in California routinely destroyed peace officer personnel records, to hide their contents from criminal defendants and from persons suing the police agency. In response to all of the personnel record shredding, the California legislature created a statutory scheme, which is now the exclusive method that a civil or criminal litigant in a California Superior Court case, can obtain peace officer personnel records. This Pitchess Motion procedure requires a civil or criminal litigant to file a “Motion For Discovery Of Peace Officer Personnel Records”. Unlike other criminal case motions, the motion must be filed no later than 15 court days prior to the date of the hearing (Cal. Evid. Code § 1043(a)), and must be accompanied by a copy of the police report (Cal. Evid. Code § 1046.) Also, the Pitchess Motion must be personally served on the employing police agency no later than 15 court days prior to the date of the hearing (Cal. Evid. Code § 1043(a).) Also, unlike any other discovery scheme or discovery statute, a police agency divulging Peace Officer Personnel Records in the absence of a Court order obtained via the Pitchess Motion process, is a crime (Opinion of the California Attorney General #99-503.)

Therefore, if a criminal defendant is being accused of a crime such a resisting / obstructing / delaying a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code § 148(a)(1)), or assault and/or battery on a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code § 240/241(b)), battery on a peace officer (Cal. Penal Code §§ 242/243(b)) and Cal. Penal Code § 69; using or threatening the use of force and violence to interfere with a public officers lawful performance of his / her duties. See, People v. Curtis, 70 Cal.2d 347 (1969.) Thus, since prior incidents of brutality and/or dishonesty by a peace officer are typically considered admissible evidence in these types of case (i.e. * prior acts of dishonesty – for witness impeachment purposes, and prior acts of brutality -to show the officer’s propensity for violence by the “victim” peace officer; to prove unreasonable force during event [an actual and proper defense to “contempt of cop” crimes]), such evidence must necessarily be discoverable (that is, because it’s relevant and often exculpatory, the defendant is entitled to a copy of the evidence) by a criminal defendant, as well as civil plaintiffs, under different theories of admissibility.

SO WHAT’S THE CATCH?

Here’s the catch. Cal. Evid. Code § 1045 provides in pertinent part:

“(a) Nothing in this article shall be construed to affect the right of access to records of complaints, or investigations of complaints, or discipline imposed as a result of those investigations, concerning an event or transaction in which the peace officer or custodial officer, as defined in Section 831.5 of the Penal Code, participated, or which he or she perceived, and pertaining to the manner in which he or she performed his or her duties, provided that information is relevant to the subject matter involved in the pending litigation.”

However, in the real world, the only thing that one gets from a California Superior Court Judge in a Pitchess Motion, are the names, addresses and telephone numbers of persons who either made complaints against a particular peace officer, and any those of witnesses to any such incident that’s the subject of the complaint; and that’s if you’re lucky. Notwithstanding the unambiguous language of Cal. Evid. Code § 1045(a), in a California Superior Court, one simply does not get those “records of complaints, or investigations of complaints” guaranteed to them by Section 1045, save extremely unusual cases.

One such type unusual “extremely unusual case”, is when a criminal defendant moves the Superior Court to obtain the Internal Affairs / Administrative Investigation witness statements, including the statements of the very peace officers who the defendant is being accused of committing some sort of crime against. The police fight to the death over these records. If a criminal defense lawyer somehow obtains an order compelling the employing the police agency to actually turnover these generally exculpatory documents and recordings (including impeachment and “story shaping” gems), the employing agency / entity will almost assuredly file a Petition for a Writ of Mandate with the Court of Appeal, and, if unsuccessful, Petition the California Supreme Court for Review; costing you a bloody fortune to defend yourself.

Moreover, although Pitchess v. Superior Court held that a criminal defendant may show evidence of the character of his victim to prove actions in conformity therewith, it was not until 2012 that a criminal defendant was permitted to obtain the statements of witnesses and participants to the very same incident that he/she is being criminally prosecuted for (See, Rezek v. Superior Court of Orange County (2012)); notwithstanding the most basic of Constitutional principles; the defendant’s entitlement to exculpatory evidence.

Attached are the “Pitchess Motion” documents, from a California Superior Court criminal cases, Hopefully, this example can help you in your case. Sample Pitchess Motion Notice of Motion, Declaration in support of the motion, Memorandum of Points and Authorities in support of the Motion, and the attached Notice Of Lodging Police Report in support of the Motion.

If you have a criminal or civil case, and want to find out if the Law Offices of Jerry L. Steering has exculpatory evidence on a particular police officer or deputy sheriff, please contact our staff at (949) 474-1849, or email jerrysteering@yahoo.com, and we will let you know what, if anything, we have on a particular police officer or deputy sheriff.If you have an officer that you would like to add to our Pitchess List data bank, please please contact our staff at (949) 474-1849, or email jerrysteering@yahoo.com. If you would like a sample copy of a Pitchess Motion, please also email or call, and we will provide you with those items.

Jerry L. Steering, Esq.

Law Office of Jerry L. Steering

Law Office of Jerry L. Steering, 4063 Birch Street, Suite 100, Newport Beach, CA 92660; (949) 474-1849; (949) 474-1883; jerrysteering@yahoo.com

Most, If Not All, Police Agencies Destroy Or Conceal Exculpatory Evidence, When Their Officers Abuse Civilians And Procure Their Bogus Criminal Prosecutions. Police Officers and Their Agencies Routinely Conceal and Destroy Exculpatory Evidence When They Violate Your Constitutional Rights.

Most, If Not All, Police Agencies Destroy Or Conceal Exculpatory Evidence, When Their Officers Abuse Civilians And Procure Their Bogus Criminal Prosecutions. Police Officers and Their Agencies Routinely Conceal and Destroy Exculpatory Evidence When They Violate Your Constitutional Rights.