Cases That Have Destroyed Many of Your Heretofore Civil Rights Against Police Abuse

For an overview of why Americans (almost) have no rights anymore, see Mr. Steering’s Articles:

* Why You (Almost) Have No Rights In America

* A Practical Cure for the Curse of Qualified Immunity

* How The Exclusionary Rule Backfired and Crushed Americans Constitutional Rights

* Four Steps to Curbing Police Misconduct in the United States

* Officer’s Safety has replaced Probable Cause

Ugly Fourth Amendment Search and Seizure Cases

Atwater v. Lago Vista, 532 U.S. 318 (2001)

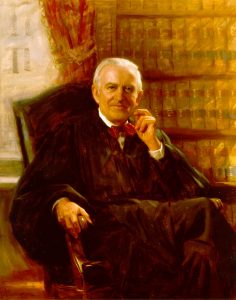

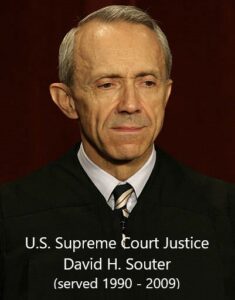

![Associate Justice David H. Souter]() Atwater v. Lago Vista is the number one reason why the police can almost always arrest you anytime that they feel like it and get away with it. Under Atwater v. Lago Vista, the police can arrest you and take you to jail for anything that the law prohibits, anything at all, no matter how trivial, even if under state law, an arrest for de minimis infractions is prohibited. as shown below, it doesn’t matter what crime the arresting officer arrested you for. It doesn’t even matter whether the arresting officer had even thought of, or had even known about the public offense that they use to justify your arrest, after the fact.

Atwater v. Lago Vista is the number one reason why the police can almost always arrest you anytime that they feel like it and get away with it. Under Atwater v. Lago Vista, the police can arrest you and take you to jail for anything that the law prohibits, anything at all, no matter how trivial, even if under state law, an arrest for de minimis infractions is prohibited. as shown below, it doesn’t matter what crime the arresting officer arrested you for. It doesn’t even matter whether the arresting officer had even thought of, or had even known about the public offense that they use to justify your arrest, after the fact.

All that does matter is whether the fictional reasonably well-trained peace officer in the abstract could have entertained a strong suspicion (i.e. “probable cause“) that you committed a anything that the law prohibits, no matter how trivial / de minimis.

In Atwater, the Supreme Court (Justice David Souter) held that the subject arrest for a violation of the Texas seat-belt statute, the maximum penalty for which is a $50.00 civil fine, did not violated for Fourth Amendment. So, if you go one mile per hour over the posted speed limit, and the police arrest you for failing the attitude test (i.e. resisting / obstructing / delaying peace officer) you cannot successfully sue the arresting officer for false arrest.

In the real world, under Atwater, you now (almost) have no right to be free from an arrest of your person.

Devenpeck v. Alford, 543 U.S. 146 (2004)

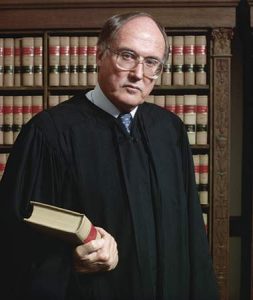

![Justice Antonin Scalia author of Devenpeck v. Alford]() In Devenpeck v. Alford, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals “Closely Related Offense Doctrine”, and held that the Fourth Amendment does not require that probable cause existed for the crime that the police arrested you for, so long as in retrospect, the fictional reasonably well-trained officer in the abstract could have had probable cause to believe that you committed any crime at all; anything that the law prohibits, even if that crime is not at all “Closely Related” to the arrest crime, and even if the arresting officer never thought of the public offense that is now being used to justify your arrest.

In Devenpeck v. Alford, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals “Closely Related Offense Doctrine”, and held that the Fourth Amendment does not require that probable cause existed for the crime that the police arrested you for, so long as in retrospect, the fictional reasonably well-trained officer in the abstract could have had probable cause to believe that you committed any crime at all; anything that the law prohibits, even if that crime is not at all “Closely Related” to the arrest crime, and even if the arresting officer never thought of the public offense that is now being used to justify your arrest.

In Devenpeck v. Alford, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that if the police arrest you for a crime that they did not have probable cause to believe that you committed, if the police want to later-on justify their arrest of you, the crime that they point to that they did have probable cause to arrest you for be “closely related” to the offense for which you were arrested. Now, under Devenpeck v. Alford, it doesn’t matter what crime the police arrested you for or even thought of when your were arrested, so long as later-on down the road, the police can show that the reasonably well-trained officer in the abstract (that is, not the cop who arrested you but some imaginary officer), would have had probable cause to arrest you for something that the law prohibits.

So, now, under Devenpeck v. Alford if the police arrest you for murder, but one of your car’s taillights were out, you can no longer sue for your false arrest for murder. Devenpeck v. Alford is truly an ugly 4th Amendment case.

Whren v. United States, 517 U.S. 806 (1996)

![Traffic stop leads to drug bust in Fort Myers ...]() It doesn’t matter what crime the police detained or arrested you for, so long as in retrospect, given the facts known to the police officer, whether the fictional reasonable police officer in the abstract would have had probable cause to believe that you committed any crime at all; any crime, including any infraction.

It doesn’t matter what crime the police detained or arrested you for, so long as in retrospect, given the facts known to the police officer, whether the fictional reasonable police officer in the abstract would have had probable cause to believe that you committed any crime at all; any crime, including any infraction.

“The temporary detention of a motorist upon probable cause to believe that he has violated the traffic laws does not violate the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition against unreasonable seizures, even if a reasonable officer would not have stopped the motorist absent some additional law enforcement objective.”

The issue in Whren v. United States was whether crack cocaine found in a car pursuant to a lawful vehicle stop for minor traffic infraction was admissible at Whren’s criminal trial. Whren contended that the officers used the pretense of making a traffic stop to investigate for evidence of other crimes.

The U.S. Supreme Court held the District Court’s finding that the officers had probable cause to believe the defendants had violated the District of Columbia’s traffic code justified the traffic stop. Therefore, as the traffic stop was reasonable/lawful under the 4th amendment, the evidence of the crack cocaine was admissible at Whren’s criminal trial, regardless of whether the arresting police officer’s subjective motivation in stopping the vehicle was to search for drugs, and not the traffic violation; in other words, a pre-text traffic stop.

In other words, it does not matter what the subject intent of a police officer was in stopping or detaining or arresting another, so long as the reasonable police officer in the abstract, could have believed that probable cause existed to detain or arrest another for any crime; even a de minimis traffic infraction.

Whren v. United States is significant because it puts — front and center — the issue of police using traffic infractions as a reason to stop vehicles in order to discover more serious crimes, and also the dangers involved in racial profiling. While the Court acknowledges the reality of those issues, it still found that the existence of probable cause for any violation can justify a car stop.

Now, under the guise of “Officer Safety”, the police can detain you, point guns at you, order you to lie down on the ground, order you to get out of your home, handcuff you, frisk you, confine you in a police car, and search your vehicle and your home; all without a warrant, and all without any real suspicion by the police that you have committed a crime.

Kentucky v. King, 563 U.S. 452 (2011)

In Kentucky v. King, the Supreme Court dispensed with the longstanding judicial recognitions that the police cannot use a “do it yourself emergency” to justify dispending with the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement.

In Michigan v. Summers, 452 U.S. 692 (1981), police officers were executed a search warrant for illegal narcotics a private residence. When they arrived there, they found a man walking out of the house and attempting to exit the property. The Supreme Court held that since a neutral and detached Magistrate made a finding that there was probable cause to have believed that illegal narcotics were in the house, that the police could reasonably rely on the warrant for contraband (something illegal to possess) in suspecting that anyone found at the residence could be initially detained; at least until their status was determined.

“If the evidence that a citizen’s residence is harboring contraband is sufficient to persuade a judicial officer that an invasion of the citizen’s privacy is justified, it is constitutionally reasonable to require that citizen to remain while officers of the law execute a valid warrant to search his home.19 Thus, for Fourth Amendment purposes, we hold that a warrant to search for contraband20 founded on probable cause implicitly carries with it the limited authority to detain the occupants of the premises while a proper search is conducted.“ 21

In Summers, the Supreme Court explicitly stated that they were not holding that in non-contraband search warrant executions that persons who were not the target of the search warrant, or who were not suspected of criminal activity, could be detained:

Summers, Footnote 20:

“We do not decide whether the same result would be justified if the search warrant merely authorized a search for evidence. Cf. Zurcher v. Stanford Daily, 436 U.S. 547, 560, 98 S.Ct. 1970, 1978, 56 L.Ed.2d 525. See also id., at 581, 98 S.Ct., at 1989 (STEVENS, J., dissenting).

Twenty four years later in Muehler v. Mena, 544 U.S. 93 (2005), the Supreme Court abandoned its reasonable suspicion of criminality to detain another during a search warrant execution altogether, in the name of officer’s safety, with no connection to crime:

“Mena’s detention in handcuffs for the length of the search did not violate the Fourth Amendment. Thatdetention is consistent with Michigan v. Summers, 452 U.S. 692, 705, in which the Court held that officers executing a search warrant for contraband have the authority “to detain the occupants of the premises while a proper search is conducted.” The Court there noted that minimizing the risk of harm to officers is a substantial justification for detaining an occupant during a search, id., at 702—703, and ruled that an officer’s authority to detain incident to a search is categorical and does not depend on the “quantum of proof justifying detention or the extent of the intrusion to be imposed by the seizure,” id., at 705, n. 19. Because a warrant existed to search the premises and Mena was an occupant of the premises at the time of the search, her detention for the duration of the search was reasonable under Summers. Inherent in Summers’ authorization to detain is the authority to use reasonable force to effectuate the detention. See Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 396. The use of force in the form of handcuffs to detain Mena was reasonable because the governmental interest in minimizing the risk of harm to both officers and occupants, at its maximum when a warrant authorizes a search for weapons and a wanted gang member resides on the premises, outweighs the marginal intrusion. See id., at 396—397. Moreover, the need to detain multiple occupants made the use of handcuffs all the more reasonable. Cf. Maryland v. Wilson, 519 U.S. 408, 414. Although the duration of a detention can affect the balance of interests, the 2- to 3-hour detention in handcuffs in this case does not outweigh the government’s continuing safety interests. Pp. 4—7.” (Rehnquist, C.J.)

This language in Muehler v. Mena is a deliberate mischaracterization (they’re not stupid; they know what they’re doing), of the Summers Court’s basis for the seizure of the occupants of the residence during a search warrant execution for narcotics. As shown above, in Summers, the Supreme Court specifically stated, that since a judge had made a determination that there is probable cause to believe that there is “contraband” at a particular home, so they implicitly had enough reasonable suspicion of criminality afoot (connection to ongoing crime) to justify detaining persons found at the home. That is, Summers only approved the basis for detaining the occupants of the home, based on suspicion that any occupants of the home were in possession of narcotics. The Majority in Muehler v. Mena has has the “chutzpah“, to predicate their deviation from the Fourth Amendment’s clear command, that their be some connection between the seizure of a person by the government, and their connection to crime; that is, other than for “civil protective custody” (i.e. taking someone medically or mentally impaired, for their own protection.

Muehler v. Mena was the first time that the United States Supreme Court permitted the seizure of a person (i.e. detention or arrest), without any suspicion that the person had been, or was engaged, or about to be engaged in criminal activity. Thus, “Officer Safety”, and not the Fourth Amendment, wins the balancing of interest contest, over suspicion of criminal activity to justify a seizure of a person. They win, you lose. Rather than simply obey the language of the Fourth Amendment (i.e. Probable Cause needed for a seizure of a person by police), slowly but surely, case by case, the Supremes are chopping-down the beams holding-up the altar of freedom.

Ugly First Amendment Free Speech Cases

The Greatest Threat to American’s Constitutional Rights; Qualified Immunity:

The Doctrine of Qualified Immunity Precludes Americans from Obtaining Redress for Violation of Their Constitutional Rights in a Number of Settings

Qualified Immunity – General Concepts

The doctrine of qualified immunity protects police officers and other government officials “from liability for civil damages insofar as their conduct does not violate clearly established statutory or constitutional rights of which a reasonable person would have known.” Harlow v. Fitzgerald, 457 U.S. 800, 818 (1982).

Qualified immunity is “an immunity from suit rather than a mere defense to liability.” Hunter v. Bryant, 502 U.S. 224, 227 (1991).

In resolving qualified immunity claims, “[a] court must decide . . . whether the facts [that a plaintiff has] alleged or shown . . . make out a violation of a constitutional right, and . . . whether the right at issue was ‘clearly established’ at the time of defendant’s alleged misconduct.” Pearson v. Callahan, 555 U.S. 223 (2009).

A police officer defendant is entitled to qualified immunity unless the conduct “violated a clearly established constitutional right.” Pearson v. Callahan, 555 U.S. 223 (2009).

*

In

In