Civil Rights Cases under 42 U.S.C. § 1983; The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871.

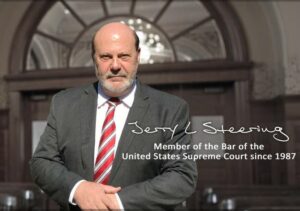

Jerry L. Steering is a civil rights lawyer who sues police officers and others under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 since 1984. He is an expert in these “Section 1983 cases”, and can help you obtain whatever vindication of your federal Constitutional rights is available to you based on the facts of your particular case. Almost every one of Mr. Steering’s civil rights cases involve allegations that some peace officer or other person acting under the color of state law, violated his client’s federal and/or state constitutional rights.

Jerry L. Steering is a civil rights lawyer who sues police officers and others under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 since 1984. He is an expert in these “Section 1983 cases”, and can help you obtain whatever vindication of your federal Constitutional rights is available to you based on the facts of your particular case. Almost every one of Mr. Steering’s civil rights cases involve allegations that some peace officer or other person acting under the color of state law, violated his client’s federal and/or state constitutional rights.

42 U.S.C. § 1983 – THE KU KLUX KLAN ACT OF 1871 – THE THIRD ACT TO ENFORCE THE 14TH AMENDMENT.

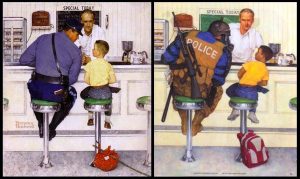

The federal statute that persons in the United States use every day to sue police officers and other persons acting “under the color of state law“, is “The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871“; 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Section 1983 was a Reconstruction Era Law enacted by Congress to enforce the mandates of the Fourteenth Amendment, and its guarantee that the protections of the federal constitution apply to all persons; especially black persons of African descent.

RATIFICATION OF THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED STATES.

In 1865 the United States abolished slavery with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment , that provides:

In 1865 the United States abolished slavery with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment , that provides:

Amendment XIII, Section 1.

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist in the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

RATIFICATION OF THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION.

In 1868, the states ratified the Fourteenth Amendment to mandate that recently freed slaves and other persons of African descent were citizens, with the same privileges and immunities as other citizens; including due process of the law; a fundamentally fair process, before a state shall deprive any person life, liberty or property. The Fourteenth Amendment provides:

Section 1.

The All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Section 5.

The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

The 14th amendment was that constitutional provision that enabled Congress to eventually make those provisions of the Bill of Rights obligatory on the states. The 14th amendment was needed to guarantee that persons of African descent were, in fact, citizens.

Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment provided the jurisdiction for Congress to provide a federal civil remedy for the violation of any persons’ federal constitutional rights, by one acting under the color of state law. This “appropriate legislation” is also that very same statute that Americans use every day to sue police officers and other persons “acting under the color of state law“, who violate their federal constitutional rights. This statute is “The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871“; 42 U.S.C. § 1983.

ENFORCEMENT OF THE 14th AMENDMENT DURING RECONSTRUCTION.

In the years after the Civil War, the South began to see the emergence of white terrorist groups.

In the years after the Civil War, the South began to see the emergence of white terrorist groups.

On December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment abolished slavery in the United States.

On July 9, 1868, the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified by the states. It extended liberties and rights granted by the Bill of Rights to formerly enslaved people.

On February 3, 1870, the 15th Amendment was ratified by the States. It granted black men of African descent the right to vote.

The Confederacy had lost 483,026 soldiers in the Civil War; men lost defending slavery; an institution based on the premise of White Supremacy, and the belief by Southerners that the “dominant race” had the moral and legal right to have subjected the “servient race” to chattel slavery. See, Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1856).

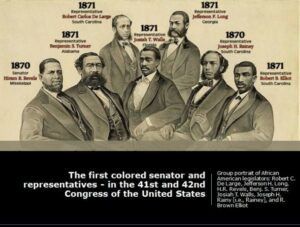

With the enactments of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments, many of the U.S. Senators and U.S. Representatives from the Southern States were black persons. As one might imagine, the Southerners were not happy with black persons not only being freed from bondage, but now representing them in Congress.

The South’s response to these Constitutional Amendments, and to black persons now being their Senators and Representatives, was the emergence of White Supremacist terrorist organizations. These organizations of composed mostly of veterans still aspiring to the goals of the Confederacy and their own Southern heritage, brought terror to freed blacks who looked to participate in the community as well as to their white allies.

Founded as a fraternal organization by Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1866, the Ku Klux Klan soon became a paramilitary group devoted to the overthrow of Republican governments in the South, and the reassertion of white supremacy. Klansmen were local Southern Sheriffs and their deputize posse members; person acting under the color of state law. Through murder, kidnapping, and violent intimidation, Klansmen sought to secure Democratic victories in elections by attacking black voters and, less frequently, white Republican leaders.

Founded as a fraternal organization by Confederate veterans in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1866, the Ku Klux Klan soon became a paramilitary group devoted to the overthrow of Republican governments in the South, and the reassertion of white supremacy. Klansmen were local Southern Sheriffs and their deputize posse members; person acting under the color of state law. Through murder, kidnapping, and violent intimidation, Klansmen sought to secure Democratic victories in elections by attacking black voters and, less frequently, white Republican leaders.

CONGRESS’ RESPONSE TO WHITE SUPREMACIST TERRORISM; 42 U.S.C. § 1983 – THE KU KLUX KLAN ACT OF 1871 – THE THIRD ACT TO ENFORCE THE 14TH AMENDMENT.

In an effort to protect the rights of black persons in the South, Congress Enacted Three “Enforcement Acts” between 1870 and 1871. These acts were specifically designed to protect African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and to receive equal protection of laws. The three bills passed by Congress were the Enforcement Act of 1870, the Enforcement Act of 1871, and the Ku Klux Klan Act.

In May 1870, Congress enacted the First Enforcement Act to restrict the Ku Klux Klan and other terrorist organizations from harassing and torturing African Americans. The Act prohibited individuals from assembling or disguising themselves with intentions to violate African Americans’ constitutional rights. The Act outlined criminal penalties for those who chose to interfere with a citizen’s right to vote.

In February of 1871, Congress Enacted The Second Enforcement Act of 1871, sometimes called the Civil Rights Act of 1871 or the Second Ku Klux Klan Act. The Second Enforcement Act amended the first Enforcement Act by adding more severe punishments to the revisions. This act was best enforced by the United States Government.

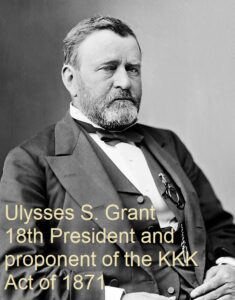

On March 23, 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant sent a message sent to Congress by reading:

“A condition of affairs now exists in some States of the Union rendering life and property insecure and the carrying of the mails and the collection of the revenue dangerous. The proof that such a condition of affairs exists in some localities is now before the Senate. That the power to correct these evils is beyond the control of State authorities I do not doubt; that the power of the Executive of the United States, acting within the limits of existing laws, is sufficient for present emergencies is not clear. Therefore, I urgently recommend such legislation as in the judgment of Congress shall effectually secure life, liberty, and property, and the enforcement of law in all parts of the United States.”

President Grant thereafter met with Congressional leaders, and on April 20, 1871 President Grant signed into law The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871. This statute was Congress’ attempt to put an end to the policies of terrorism, intimidation, and violence that the Klan, the Knights of the White Camelia, and the Jayhawkers had been using.

Also known as “The Third Enforcement Act”, the bill was a controversial expansion of federal authority, designed to give the federal government additional power to protect voters. The act established penalties in the form of fines and jail time for attempts to deprive citizens of equal protection under the laws and gave the President the authority to use federal troops and suspend the writ of habeas corpus in ensuring that civil rights were upheld.

President Grant put the new legislation to work after several Klan incidents in May. He sent additional troops to the South and suspended the writ of habeas corpus in nine counties in South Carolina. Aided by Attorney General Amos T. Akermen and the newly created Department of Justice, extensive work was done to prosecute the Klan. While relatively few convictions were obtained, the new legislation helped to suppress Klan activities and ensure a greater degree of fairness in the election of 1872.

Although The Third Enforcement Act provides for civil remedies against persons acting under the color of state law who violated the Constitutional rights of any persons, especially black persons of African descent, it was enforced by the government; not by private parties. It was not until 90 years later that The Third Enforcement Act was permitted by the Supreme Court to allow private persons to sue persons acting under the color of state law (i.e. the police and other government officials) for the violation of their federal constitutional rights.

USE OF THE KU KLUX KLAN ACT OF 1871 AS A CIVIL REMEDY IN FEDERAL COURT TO SUE THE POLICE FOR VIOLATION OF CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS.

A Private Right of Action for Violation of the Ku Klux Klan Act OF 1871 – Monroe v. Pape.

In Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) thirteen Chicago police officers broke into James Monroe’s home in the early morning, routed him and his family from their beds, made them stand naked in the living room, and ransacked every room, emptying drawers and ripping mattress covers. Mr. Monroe was then taken to the police station and detained on “open” charges for 10 hours, while he was interrogated about a two-day-old murder, that he was not taken before a magistrate, though one was accessible, that he was not permitted to call his family or attorney, that he was subsequently released without criminal charges being requested or filed against him.

James Monroe alleged that the officers had no search warrant and no arrest warrant and that they acted “under color of the statutes, ordinances, regulations, customs and usages” of the State of Illinois and of the City of Chicago.” The City of Chicago moved to dismiss the complaint on the ground that it is not liable under the Civil Rights Acts nor for acts committed in performance of its governmental functions. All defendants moved to dismiss Mr. Monroe’s lawsuit, alleging that the Complaint alleged no cause of action under those the Third Enforcement Act, or under the Federal Constitution.

The District Court dismissed the complaint and the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit affirmed the dismissal, relying on its earlier decision, Stift v. Lynch, 267 F.2d 237 (7th Cir. 1959).

In reversing the Court of Appeals, the Supreme Court held for the first time since the enactment of Third Enforcement Act , that 42 U.S.C. § 1983 provides a private right of action against the individual Chicago police officers, even though that statute provided no civil remedy against the City of Chicago:

“It authorizes any person who is deprived of any right, privilege, or immunity secured to him by the Constitution of the United States, to bring an action against the wrongdoer in the Federal courts, and that without any limit whatsoever as to the amount in controversy. The deprivation may be of the slightest conceivable character, the damages in the estimation of any sensible man may not be five dollars or even five cents; they may be what lawyers call merely nominal damages; and yet by this section jurisdiction of that civil action is given to the Federal courts instead of its being prosecuted as now in the courts of the States . . .

. . . The response of the Congress to the proposal to make municipalities liable for certain actions being brought within federal purview by the Act of April 20, 1871, was so antagonistic that we cannot believe that the word ‘person’ was used in this particular Act to include them. Accordingly we hold that the motion to dismiss the complaint against the City of Chicago was properly granted. But since the complaint should not have been dismissed against the officials the judgment must be and is reversed.” Douglas, J., Majority Opinion.

Section 1983 Cases In The Modern Era; Our Remedy For Constitutional Violations By State And Local Officials.

42 U.S.C. § 1983, provides:

“Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress, except that in any action brought against a judicial officer for an act or omission taken in such officer’s judicial capacity, injunctive relief shall not be granted unless a declaratory decree was violated or declaratory relief was unavailable. For the purposes of this section, any Act of Congress applicable exclusively to the District of Columbia shall be considered to be a statute of the District of Columbia.”

Section 1983 is not itself a source of substantive Constitutional rights, but merely provides a method for vindicating federal rights conferred in the federal Constitution itself. Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 393-94 (1989.) In other words, Section 1983 is a federal statute that doesn’t define any Constitutional rights, but merely provides a civil remedy for persons whose federal Constitutional rights have been violated. So, when the policeman falsely arrests you, you can sue the cop under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for violation of your federal Constitutional rights under the Fourth Amendment, as being the victim of an unreasonable seizure of your person. So, when the policeman beats-you-up for telling him that you know your rights and he has no right to search your car, you can sue him under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for violation of your federal Constitutional rights under the Fourth Amendment for an unreasonable seizure of your person under the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and, for violation of your First Amendment right to free speech / right to petition government for redress of grievances, for retaliating against you for your right to protest police actions. Duran v. City of Douglas, 904 F.2d 1372 (9th Cir. 1990.)

If you believe that a government official, including police officers, violated your Constitutional rights, please contact us about your case.

WHAT YOU CAN DO.

Someone has to stand-up to the bullies of society, who think that using state police power to humiliate others, is funny, and makes them big men (or women.) There are thousands of others like you, who are good people, and have been somehow, for some reason that you could not have ever imagined, victimized by the government. It might as well be you. Stand-up for justice. Stand-up for our form of self-government. Stand-up for the spilled-blood of our fathers, who bravery died to prevent the very thing, that the government is doing to you right now.

Click on “Home”, above, or the other pages shown, for the information or assistance that we can provide for you. If you need to speak with a lawyer about your particular legal situation, please call the Law Offices of Jerry L. Steering for a free telephone consultation. Also, if you have been the victim of a False Arrest or Excessive Force by a police officer, check our Section, above, entitled: “What To Do If You Have Been Beaten-Up Or False Arrested By The Police“.

Thank you, and best of luck, whatever your needs.

Jerry L. Steering, Esq.

Law Offices of Jerry L. Steering. 4063 Birch Street, Suite 100, Newport Beach, CA 92660; (949) 474-1849; Fax: (949) 474-1883; jerry@steeringlaw.com

Proudly serving these Counties and cities and otherwise throughout California.

“A condition of affairs now exists in some States of the Union rendering life and property insecure and the carrying of the mails and the collection of the revenue dangerous. The proof that such a condition of affairs exists in some localities is now before the Senate. That the power to correct these evils is beyond the control of State authorities I do not doubt; that the power of the Executive of the United States, acting within the limits of existing laws, is sufficient for present emergencies is not clear. Therefore, I urgently recommend such legislation as in the judgment of Congress shall effectually secure life, liberty, and property, and the enforcement of law in all parts of the United States.”

“A condition of affairs now exists in some States of the Union rendering life and property insecure and the carrying of the mails and the collection of the revenue dangerous. The proof that such a condition of affairs exists in some localities is now before the Senate. That the power to correct these evils is beyond the control of State authorities I do not doubt; that the power of the Executive of the United States, acting within the limits of existing laws, is sufficient for present emergencies is not clear. Therefore, I urgently recommend such legislation as in the judgment of Congress shall effectually secure life, liberty, and property, and the enforcement of law in all parts of the United States.” “It authorizes any person who is deprived of any right, privilege, or immunity secured to him by the Constitution of the United States, to bring an action against the wrongdoer in the Federal courts, and that without any limit whatsoever as to the amount in controversy. The deprivation may be of the slightest conceivable character, the damages in the estimation of any sensible man may not be five dollars or even five cents; they may be what lawyers call merely nominal damages; and yet by this section jurisdiction of that civil action is given to the Federal courts instead of its being prosecuted as now in the courts of the States . . .

“It authorizes any person who is deprived of any right, privilege, or immunity secured to him by the Constitution of the United States, to bring an action against the wrongdoer in the Federal courts, and that without any limit whatsoever as to the amount in controversy. The deprivation may be of the slightest conceivable character, the damages in the estimation of any sensible man may not be five dollars or even five cents; they may be what lawyers call merely nominal damages; and yet by this section jurisdiction of that civil action is given to the Federal courts instead of its being prosecuted as now in the courts of the States . . .